Having recently rewatched and reviewed the movie Clue (1985), a comment in the, er, comments sent me in search of the novelisation of the film that I’d previously had no idea existed…and, well, here we are.

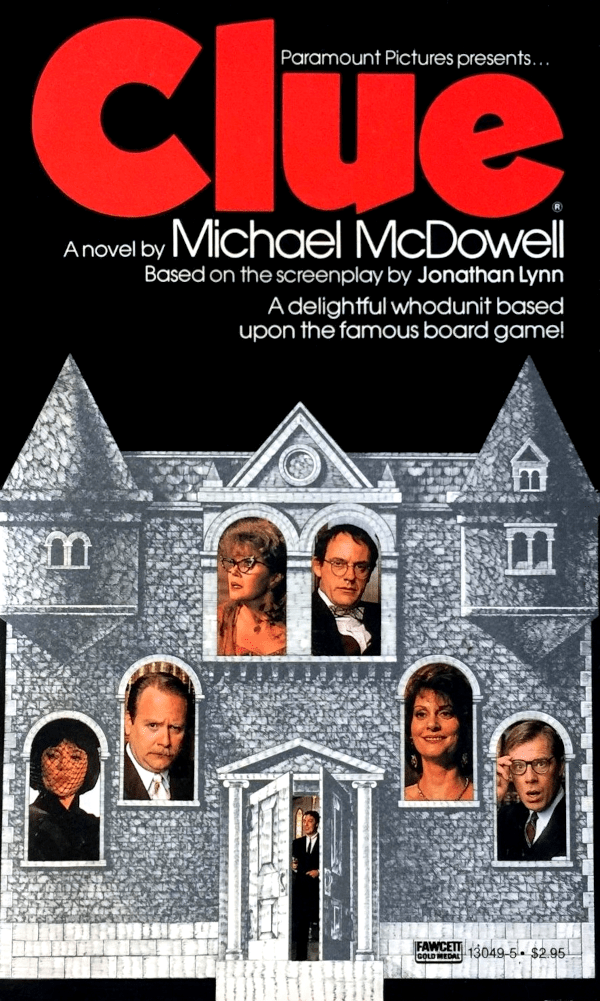

Clue (1986) by Michael McDowell, then, makes history of sorts by being only the second novelisation of a movie I’ve ever read (the first, as you’ll remember, being Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995) by D. Chiel). And I did not know what to expect: how, after all, does such a piece of media justify itself? Chiel’s book had a different denouement to the movie, one that I understand was filmed but then replaced in the final cut, and it had been suggested that McDowell’s book might add yet another solution to the whirligig that closes the film out…so, well, what happened?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, things stick pretty close to the movie for the majority: everyone arrives at the house more or less as in the film, the opening introductions of everyone to each other play out as before — all the guests are operating under pseudonyms matching characters in the board game — and just as much attention is paid to Yvette and her maid’s outfit as we’re used to, with that character getting the most, er, complete physical description of anyone present:

Yvette was not only a French maid; she was a fetishist’s dream of a French maid, and she had an outfit to match: a glossy black dress, cut high on the thigh and low in the bosom, so tight it whined when she walked. A starched white cap was perched absurdly atop her head, and a starched white apron was slung low across her waist, like a remembrance of chastity. Her stockings were at once black and sheer, and the seam that ran along the back of her calf was a draftman’s ecstasy of curve. Her shoes were high in the heel and tight in the toe, completing a figure that was — all in all — at once startling, grotesque, and divine.

What elevates the book far above it being merely a restatement of the actions of the film is McDowell’s prose, which at times veers into magnificence with the acuity of his description…

“Indeed no, sir. I am merely a humble butler.” In such a tone did Jehovah announce to Adam, I am merely the Lord of All Creation.

…yet displays common sense enough for most of the jokes to stand on their own where the script’s tight dialogue is clearly already good enough:

“We’d had a fight. He was crazy. He hated me. He had threatened to kill me in public.”

“Why would he want to kill you in public?” Miss Scarlet wanted to know.

Indeed, McDowell displays such a good eye throughout this regarding the need for the actions (soon to be) on the screen and how well they’ll translate onto the page that I was already keen to read some of his original writing well before the halfway point of this. It makes sense that the man who handled the lunacy of Beeltejuice (1988) could convey the harum-scarum antics in Clue to clearly, and I’m very curious to see what other delights his imagination cooked up — so expect the Jack and Susan books he wrote to show up on here just as soon as I’m able to track one down (that is: don’t hold your breath).

There’s a different dynamic between Mr. Boddy and the butler Wadsworth when the former comes into proceedings…

“I’m supposed to be polite,” Wadsworth said evenly. “Though when talking to you, I find that the task is almost beyond me.”

Yet it was with utmost politeness and butlerial propriety that Wadsworth took Mr. Boddy’s coat, hat, and umbrella and carefully hung them up on the rack that held the belongings of the other guests.

“Just one thing — ‘Wadsworth.’” Mr. Boddy added a sneer to his voice as well. “Remember, I know who you really are. And don’t you forget it.”

…but then everything proceeds pretty much exactly as you’ve come to know, with the various other characters cropping up, getting killed, and the lights going out and coming back on again and all the chaos of everyone running around very astutely conveyed without needless confusion or clutter…just with the added bonus of the occasional line that can’t help but catch the eye.

The others returned, more or less to their former places, and tried to maintain an appearance of normality, despite the presence of the corpse in the middle of the room.

Still, it was a presence that was impossible to ignore, like a dwarf at a wedding.

McDowell also plays the game in the best traditions of the genre when, just before the denouement, there’s a fourth-wall-breaking address to the reader…not so much a challenge as a primer of what’s to come:

Everyone knows that the best part of any whodunit is trying to figure out who committed the crime before the author tells all. You near the end of the book with delicious anticipation… were you right??? We have now reached that point in our story where we should reveal who perpetrated these dastardly deeds.

We then get four versions of chapter 20 — A, B, C, and D — which is, yes, one more than the final cut of the film.

Three of them are the ones you’ve more than likely seen already, with the same motivations and essential structure, and the fourth is…new. It’s good, it works perhaps slightly less well than the others — we’ll get to that in a minute — but, given that it’s presented third (the order here is different to the final film, interestingly) it works perfectly well in the vorticular nature of those closing reversals. There’s even a very clever swipe at a fifth solution within it, but to say more would be to spoil things for anyone who is hoping to read this at some point.

So, all told, the novelisation is something of a small triumph, building on the book with its swift prose and thumbnail portraits of people and mood. What’s sometimes interesting is what’s not here (of Mrs. White’s “Flames on the side of my face…” speech there is nary a hint, but the more I watch the film the more convinced I am that Madeline Kahn improvised that in the moment) and what clearly was never going to work when the reader is the one doing the work (the “U.N.O. W.H.O.” joke is pointed out much more obviously, for one).

There’s also the distinct advantage the film has over the book in that, to allow those multiple solutions, it obviously matters who is present at certain times. Lynn’s movie got around this with lots of scurrying shots of a crowd of people, well-blocked so that the eye doesn’t necessarily pick up on who’s absent until you know you’re looking out for it. A book lacks that advantage — were McDowell to tell you who was present at every turn, it would make for a) tedious reading and b) less in the way of closing surprises. So when someone says, essentially, ‘Everyone ran to the kitchen, except X who went to another room and did a crime and we just didn’t notice they weren’t with us…’, well, you just have to accept it, and that’s rather unsatisfying. There’s an interesting reflection to be had on how the visual medium has this distinct advantage over the written one, but I sincerely doubt that I’m the person to write it.

As a novel of detection, then, Clue presents similar problems to the script that gave rise to it, since the multiple endings can have no dominant clue to conclusively indicate the answer. As a piece of pure entertainment, however, it’s difficult to dislike, being wonderfully written (“[H]er hair was as black as Judith’s the morning she struck off the head of Holofernes.”) and maintaining the intended spirit of the film that would have brought you here. If you love the film and want to experience it in a faithful, alternative way, you could do far, far worse than this.

~

Big thanks to my friend Claire who, when I mentioned it in passing, remembered that she had a copy in her attic and dug it out for me to read. It amuses me greatly that the two novelisations I’ve now read are linked in a very key way. Maybe this is a sign I should read no more, eh? Or that I should only read ones that allow the property to be repeated…