I’ve been planning this for over a year, since reviewing the British Library’s fifth collection of Christmas short stories last November. Finally, then, December will see me reviewing Christmas-themed books for perhaps the first time since starting this blog in 2015, with a second BL collection coming in the weeks ahead.

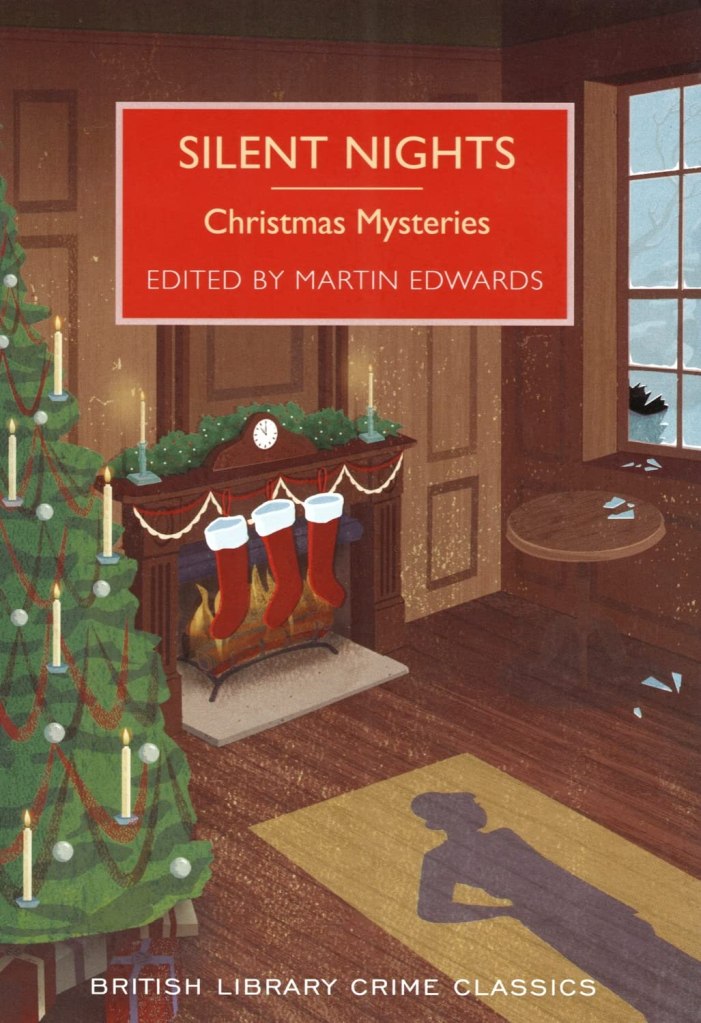

Today it’s the turn of Silent Nights (2015), which I believe was the very first Christmas collection Martin Edwards wrangled for the British Library Crime Classics range, and which I’ve been told represents one of the high points of these very enjoyable collections. It’s no small feat to comb together a set of stories on some of the themes Edwards has been dealt, so let’s see how he acquitted himself here.

We begin with a popular hors d’oeuvre in ‘The Blue Carbuncle’ (1892) by Arthur Conan Doyle. I didn’t reread this because I’ve already covered it on here, and I’m not sure I have anything to add to my thoughts. It strikes me as a most unlikely story, and were the central character anyone but Sherlock Holmes I have a feeling it might linger unloved on the fringes of the genre’s memory. But it’s jolly enough, gets things off to a suitably cockle-warming start, and I’d be a humbug if I objected to it on any grounds.

Another appetiser is served up via the very entertaining ‘Parlour Tricks’ (1930) by Ralph Plummer, which revolves around the snowed-in denizens of a nameless hotel, who are being entertained by various playful means dreamed up by the ingenuity of fellow guest Eric Glover. It’s pleasingly very difficult to get a sense of where this is going until it gets there, and it’s a light and fun story with some good ideas. Edwards expresses a desire for Plummer to be better known, and it’s difficult to disagree on this evidence.

Next, ‘A Happy Solution’ (1916) by Raymund Allen, one of apparently several chess-based mysteries he wrote, here using the game as background to Kenneth Dale’s fiancée Norah being accused of a theft in a house she is visiting for the first time. There’s a clever idea at the heart of this, no doubt, but all the chess talk required to resolve the situation did, I cannot lie, make my eyes glaze over, and so was rather lost on my ignorant brain.

Allen writes well, though, and gives a strong sense of character in only a few words, with Kenneth’s stiffly suspicious Aunt Blaxter an especially fascinating creation given how little she says and does while on the page. I just wish the central deduction didn’t make me feel so dim.

I’m warming up to the verbosity of G.K. Chesterton, but rereading ‘The Flying Stars’ (1911) makes me appreciate the gulf that exists between his stronger and weaker work. This, for me, is one of the latter category, with a Christmas masquerade party resulting in theft and Father Brown on the scene to appeal to a thief’s soul.

Chesterton is having fun, as he nearly always seems to be — see his comments about socialists — but this is light stuff devoid of the sort of paradoxes that make his stronger stories sing. He elucidates the chaos of a Christmas house party well, but as a plot this leaves, for this reader, a lot to be desired. But that’s fine, it just means my Chesterton conversion will be all the more affecting when it finally occurs.

We’re into the main course by now. Adding to my feeling that more attention should be paid Edgar Wallace, ‘Stuffing’ (1926) is a fun patchwork of a story in which our omniscient narrator employs a delightfully arch tone (“He had long ceased to be associated with the Press, save as a subject for its crime reporters…”) on the way to a theft that goes off badly due to the damn cussedness of events in particular.

On form like this it’s difficult to object to Wallace, such as his catty characterisation of dim bulbs John and Angela Willett that “[h]e was confident that he would one day be a great engineer [and s]he also believed in miracles”, and while its relies on coincidence to work, only a hard heart could object to this on any serious grounds.

‘The Unknown Murderer’ (1923) is another welcome use of the work of H.C. Bailey, who has haunted a good many short story collections of late and surely deserves his own raft of reprints by now. This sees a murder at a Christmas fair at an orphanage where Reggie Fortune is in attendance with his fiancée and, inevitably, gets drawn into the investigation. It’s brisk, and I find Fortune good company, not least because Bailey’s slightly old-world way of writing seems to carry so much humour about its ever-quirking lips:

After two changes [of train] Reggie arrived, cold and with a railway sandwich rattling in his emptiness, on the dimly lit platform of Blackover.

It’s in the closing stages that Mr. Fortune becomes especially interesting, though, with the deficiencies in clewing and deduction made up for by…well, I’ll not spoil it, but it makes me want to read a lot more Bailey very soon.

I’ve definitely read ‘The Necklace of Pearls’ (1931) by Dorothy L. Sayers before, but a scouring of my shelves and memory does not reveal the source…so has someone else explained away this apparently-impossible theft of the eponymous jewellery in the same way? The whole thing positively beams with festive cheer, thanks in no small part to Sayers’ phenomenal acuity with language — c.f. the household after lunch captured as “[g]orged and dyspeptic and longing only for the horizontal position.” I’ve come to enjoy Sayers much more through her short fiction, and this is no exception to that. I can feel the itch to take on one of her longer works growing, so let’s see how that pans out.

It is to the credit and, very slightly, the detriment of ‘The Absconding Treasurer’ (1927) by J. Jefferson Farjeon that the milieu of some stolen money and a missing man is allowed to play out so organically, with very little in the way of narrative shoving to bring the events into a clear pattern for the reader. I could have done without all the phonetic speech (“Ted Blake ‘ere never ‘eard ‘him, and ‘e sleeps oppersit.”) but the Simenon-esque unravelling of this, all the way down to its grubby and miniscule conclusion, sits well against the convolutions elsewhere.

What I can tell you about ‘The Case is Altered’ (1938) by Margery Allingham is that it’s 20 pages long, and ten pages in I realised that I wasn’t enjoying myself, had no idea what was going on, and didn’t really care enough to find out. I continue to blow hot and cold with Allingham — The Case of the Late Pig (1937) was delightful, yet I gave up 30 pages into The Fashion in Shrouds (1938) — and this hasn’t convinced me that I need to keep going back to her.

‘Waxworks’ (1930) by Ethel Lina White sees a plucky young journalist decide to spend the night before Christmas in a waxwork museum where two people have already spent the night and died. Her intention is to record her thoughts every hour to provide copy for a story, but instead the creepiness of the setting begins to get to her, and she starts to doubt whether is is really alone.

This is wonderfully atmospheric, with some delightfully chilly lines, such as our heroine “not knowing which she feared more — a tangible enemy, or the unknown”, and White uses the setting to remarkable effect by allowing the reader’s own mind to do so much of the work. What it needs is a good payoff, and, well, that’s missing. Being merely 95% brilliant sometimes isn’t quite enough, eh?

‘Cambric Tea’ (1929) by Marjorie Bowen, one on many noms de plume used by Gabrielle Margaret Vere Long, is a superbly eerie story of a doctor having achieved fame in a cause célèbre poisoning case called in by a baronet who believes his wife is poisoning him. The to-ing and fro-ing of the psychological pressures on Dr. Bevis Holroyd are finely wrought, and matched by the almost unbearable aspect of the isolated setting.

[L]ight, slow snow was falling, a dreary dance over the frozen grass and before the grey corpses that paled, one behind the other, to the distance shrouded in colourless mist.

The “miasma of apprehension, gloom and dread” that pervades infests every corner of the plot, ending up like some horrible nightmare…with Bowen keeping you in wonderful suspense throughout as to whether Holroyd will wake up. On this evidence, Bowen deserves further exploration.

Under the name Joseph Shearing, Long also wrote ‘The Chinese Apple’ (1948), a delightfully creepy tale of Isabel Crosland, returning from Florence to take responsibility for Lucy Bayward, her recently-orphaned niece. There can be little doubt where this is heading, but good work is done with Isabel’s creeping dread at returning to a life she has clearly fled for good reason, which keeps you engaged even as the denouement becomes more and more inevitable. Suspense of a sort not unlike I’ve recently discovered in the work of Charlotte Armstrong, and I currently have no higher praise.

‘A Problem in White’ (1949) by Nicholas Blake makes a pleasing contrast to the Farjeon story above, in that it, too, seems to evolve organically, with its characters originally referred to by their Type (the Expansive Man, the Forward Piece, the Flash Card), and then, once the train they’re all on runs into a snow drift, slowly evolves into something decidedly more complex.

But the end, it’s almost a little head-spinning trying to keep track of the who, when, and why, but I thoroughly enjoyed the Challenge to the Reader that results in the solution being included at the back of the book. And, well, that solution shows the sort of puzzle plotting acumen that I’ve not seen in Blake before: some clever reasoning, canny hiding of glaring clues, and neat explanations for the whole shebang. If his novels were more like this, I might be tempted to try reading them again.

Another story that I’d read before, ‘The Name on the Window’ (1951) by Edmund Crispin upholds the standard to date. An impossible crime of the no footprints variety, this sees a man enter a dusty pavilion after which he is stabbed and writes his attacker’s name on the window to condemn him…except only the victim’s shoe marks are in evidence on the begrimed floor. I enjoyed this more second time around, having divined the method on first reading, and love the final line, which shows the glint of steel which shines through Crispin’s ostensibly comedic writing. The only shame is that the motive comes out of nowhere and, surely, doesn’t make much sense.

As dessert, ‘Beef for Christmas’ (1957) by Leo Bruce, in which the always-underrated ex-Sergeant William Beef is invited to spend Christmas with a millionaire and drags Lionel Townsend along as “[t]here may be a story to write”:

“[W]hat does he want us for?”

“Me, he wants. He hasn’t said anything about you.”

Threatening letters are the order of the day, with Merton Watlow convinced that one of his family is guilty, and some good mood writing that almost veers into HIBK territory (“[I]t did not save a human life.”). The setting is well-limned, and Bruce’s casually comic eye is put to good effect, it’s just a shame, as with the Crispin, that the motive is so completely occluded from the reader, once again only introduced after the crime is solved. This, nevertheless, is easily one of Bruce’s strongest short works.

I’ve taken to picking a top five for short story collections, and here they’d be…

- ‘Cambric Tea’ (1929) by Marjorie Bowen

- ‘Parlour Tricks’ (1930) by Ralph Plummer

- ‘The Unknown Murderer’ (1923) by H.C. Bailey

- ‘The Chinese Apple’ (1948) by Joseph Shearing

- ‘A Problem in White’ (1949) by Nicholas Blake

Wonderful to note that these are all stories which are new to me in this collection, testament to the work Edwards does in his curation. Wonderful, too, that if I were to extend this list to the top 10 stories in the collection, it would represent only a very slight drop off in quality from top to bottom, since the Allen, Bruce, Sayers, Wallace, and White stories are all equally strong.

It’s possible to see, from these lofty heights, why the enthusiasm for the classic Christmas crime story remains undimmed, and easy to understand that the BL might commission four more such collections on the spot having seen this. It really is a superb body of festive bodies, and bodes very well for Crimson Snow [ss] (2016) in a fortnight. In the meantime, stay warm, stay safe, and maybe don’t go investigating any bumps in the festive night…

~

British Library Crime Classics anthologies on the Invisible Event, edited by Martin Edwards

Capital Crimes: London Mysteries (2015)

Silent Nights: Christmas Mysteries (2015)

Crimson Snow: Winter Mysteries (2016)

Continental Crimes (2017)

Foreign Bodies (2017)

The Long Arm of the Law (2017)

Final Acts: Theatrical Mysteries (2022)

Crimes of Cymru: Classic Mystery Tales of Wales (2023)

Who Killed Father Christmas? and Other Seasonal Mysteries (2023)

As If by Magic: Locked Room Mysteries and Other Miraculous Crimes (2025)

The bloodied Santa hat is brilliant!

I am hoping to read last year’s BL xmas anthology this month.

LikeLike