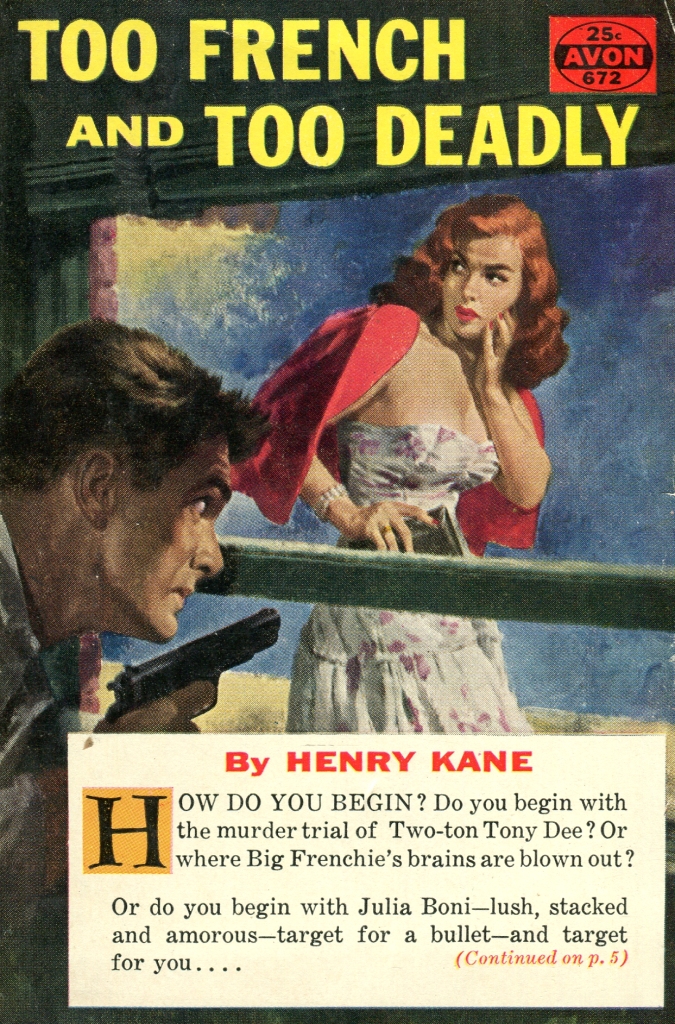

Having thoroughly enjoyed the hard-edged cynicism of P.I. Peter Chambers in Death on the Double (1957), which had an impossible crime in it just to add to the fun, I sought out Too French and Too Deadly, a.k.a. The Narrowing Lust (1955) due to Adey promising me similarly impossible happenings.

Amusingly, this starts with Chambers shaving off his moustache because he is smitten with nightclub owner Carlotta Cain — “Carlotta the beautiful, Carlotta the desirable, Carlotta of the dark and dreamy eyes…” — and understands that she doesn’t like facial hair. When he gets to the Cain Club, he’s moderately put out when his conversation with Carlotta is interrupted by Gordon Clark, a long-time friend of the object of his desire, and stalks off in a huff when asked to wait while Carlotta completes some business elsewhere.

Four days later, Chambers’ interest rises again when Ms. Cain call at his office, worried that Gordon Clark seems to have disappeared, and — long story short — soon Chambers discovers Clark’s body, gun in hand, a bullet in his stomach, in a locked office inside a locked garage…no windows in evidence, and all the doors bolted on the inside.

Death on the Double was composed of two novellas, and the death of Gordon Clark would be sufficient for that shorter form, so Kane pads things out a little by having some gangsters in the mix: a love triangle concerning the chanteuse Edie Rogers, gang boss Ritchie Rizzo, and Ritchie’s enforcer-in-chief Vincent Ossip, known as Frenchie. This seam of the plot seems mainly an opportunity for Chambers to crack wise and prove how tough and unbothered he is, especially when one of the above gets a gun put in their mouth and ends up “splattered” about a room — “and it did nothing for the decor”. The two plots overlap eventually, but mostly this feels like two novellas wearing a trench coat and pretending to be a full-length, real, grown up book.

My main interest here, aside from the surprisingly organic-feeling quips that litter the first-person narrative — c.f. Chambers’ hurried searching of an area being likened to “a taxidermist with a deadline working on the carcass of a buffalo” — is that body in a locked office inside a locked garage. Detective-Lieutenant Louis Parker, the Friend on the Police Force that all private investigators must have, is inclined to write it off as suicide, but Chambers, naturally, disagrees: Clark had taken out a life insurance policy mere days before, making Carlotta Cain the recipient of $10,000 if he dies, and would have known that suicide would net her nothing. And so the two go round and round, with Parker keen to put the thing to bed and Chambers raising objections that will, of course, turn out to be valid.

“How in the world could somebody have gone in there, killed him, and then arranged to have the steel entrance door bolted from within, and the inner office door bolted from within? And the office without a window, and the other windows of the joint steel-shuttered from within.”

Interestingly, it never occurs to anyone that a man committing suicide would be unlikely to shoot himself in the stomach, because, yeesh, that’s doubtless a horrible way to die — I seem to remember this exact objection being raised in another locked room case, though the title eludes me — and instead Parker and Chambers go back and forth until Chambers has a moment of realisation and tracks the murder to its source, receiving an explanation for his troubles.

It’s an explanation, incidentally, which covers the facts but doesn’t perhaps warrant the extended build up. I mean, we don’t come to late-period semi-hardboiled fare such as this for the intricacies of their ingenious murders, but Kane really did set up a double-tier locked room and then explained it away as if it isn’t one of the most tantalising prospects of the subgenre. I’m not disappointed — I enjoy Chambers too much to be disappointed with any time spent in his presence — but I can safely urge anyone coming to this for its impossible crime to look elsewhere and save your time and money.

I come away from this with the impression, after only two books, that Kane might be more suited to the novella. If anyone reading this is familiar with his work, I’d be intrigued if any of his oeuvre offered a greater plot density; this feels like an attempt to match the fast-paced ingenuity of A.A. Fair’s Cool and Lam books and comes up short because of the relative paucity of plot in each of the strands it seeks to plait into a single novel. Nevertheless, Chambers is fun, Kane’s prose is very readable, and as a break between more deliberately-plotted works these would make a lovely palate-cleanser in the years ahead.

This is a short review of a short book, and a book made even shorter by the fact that the font is so small I think it technically qualifies as an eye exam — both titles, incidentally, are equally nonsense, but then one rather feels Kane had a talent for the gaudy over the meaningful — but you can rest assured that Henry Kane and his luscious dames will make another appearance on this blog. Detection will always be my first love, but a P.I. like Peter Chambers is pretty hard not to enjoy.

I came across this in the collection The Locked Room Reader, so I assumed it was a short story. In my experience, the plot was wonderfully complex. I’m wondering now if it was wonderfully complex for a short story and your version is expanded. In that case, I’d agree with you that it’s not enough. In any event, we agree about the entertainment value of all the dames, booze, guns, and sex. I remember especially loving the banter.

LikeLike

If it was a short story expanded up to novel length, that would make a lot of sense.

Still, it’s good fun, and I sincerely doubt it will be the last I see of Peter Chambers.

LikeLike

Like James, I’m only familiar with “Too French and Too Deadly” from its inclusion in The Locked Room Reader and remember being amused without thinking too much of the locked room element, but have a soft spot for hardboiled detectives tackling impossible crimes. Sure, the locked rooms along those mean streets of Chandler and Hammett aren’t always the toughest nuts, but they certainly have entertainment value.

On that note, you and James might enjoy Roy Huggins’ 77 Sunset Strip. A collection of three interlocked novelettes based on the character from a 1950s private eye TV series with two, if I remember correctly, decent locked rooms/impossible crimes.

LikeLike

This would be better as a short story, and — as I think I say above — Kane seems more comfortable with shorter narrative arcs, so I can believe he did some great work in the shorter form. Maybe I should track down his short fiction first, assuming it’s been collected.

Huggins is noted and goes on the list, many thanks.

LikeLike