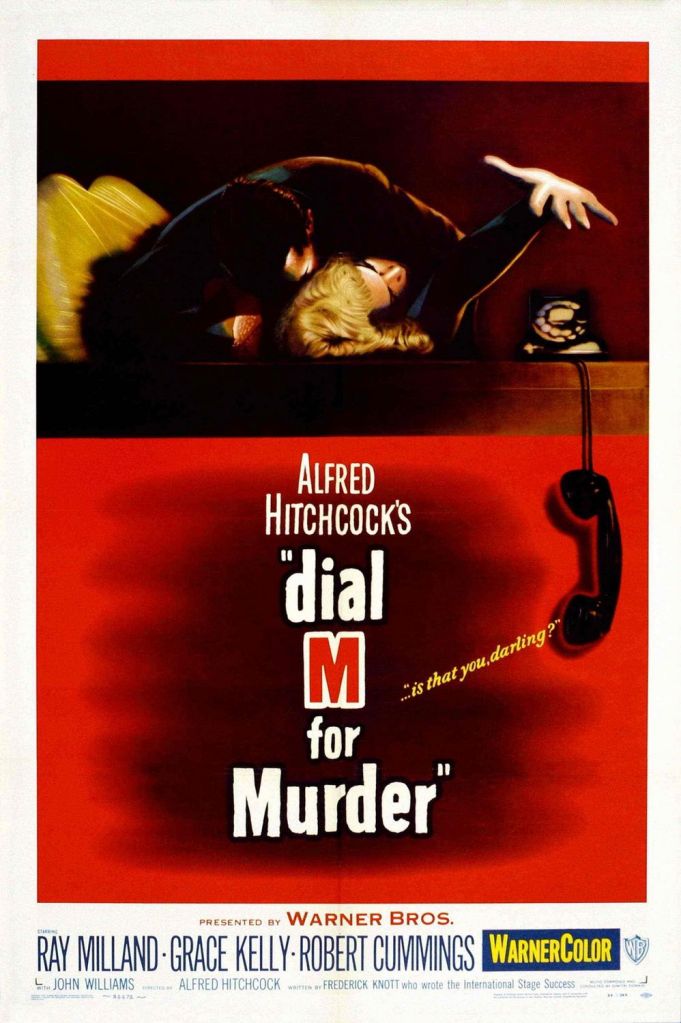

The inverted mystery has been tickling my brain recently, and I got to thinking that I’d very much like to rewatch Alfred Hitchock’s Rope (1948). But the closest thing I could find on the various platforms available to me — without shelling out any money, you understand, which must be saved for essentials like books and coffee — was the similarly-inverted Dial M for Murder (1954), which I last watched before the need to shave had descended upon me. So, well, why not?

We open with a scene of apparent cosy domesticity, with ex-tennis player Tony Wendice (Ray Milland, channelling James Stewart) and his wife Margot (Grace Kelly) at breakfast. Margot reads in the paper that crime writer Mark Halliday is due back in London and, a short transition later, it’s revealed that Margot and Mark (Robert Cummings) are in fact having an affair. As they debate whether to tell Tony about their relationship, Margot reveals that she has been blackmailed for a letter Mark had sent her previously, the only one of his letters she had not burned, though the money she sent was never claimed.

Mark and Margot go to the theatre, with Tony, who had been expected to join them, crying off due to work commitments. When the other two are out of the way, Tony phones up a certain Captain Lesgate to enquire about a car he has for sale, making up an injury as a pretext to get the man to visit him. At this meeting, it becomes clear the two men are each hiding their identity from the other, though they were in fact at Cambridge together and Tony knows Lesgate to be Charles Swann (Anthony Dawson), an ex-convict with a string of bad debts behind him.

Through a piece of economical plotting that it would be easy to overlook, so effortlessly is it deployed, Tony reveals that he stole the letter Margot was blackmailed for and in fact knows about her relationship with Mark, then traps Swann into murdering Margot. The two discuss the method with, in a lovely wry moment, Swann forgetting that Margot’s testimony on the matter is somewhat moot (“But she isn’t going to say anything, is she?”). Objects rendered previously dull and quotidian — the handle of a window, the latch on a door — then take on a magnificent significance as, the very next evening, Tony endeavours to get Mark out of the flat and leave the way clear for Swann .

Hitchcock is clever about showing small moments of real significance, like Tony slipping the fatal key under the carpet on the stairs in plain view of Margot and Mark, or the discrepancies in the times on a pair of watches, in a way that truly rewards visual storytelling, rather than speaking down to the audience to explain why these things are important. I seem to remember a quote, possibly misattributed to Steven Spielberg, along the lines that good filmmaking allows you to divine the purpose of a scene even if the sound is turned off, and this is so very true here that you can’t help but marvel at the brilliance of what you’re shown. Hell, there’s even a moment of magnificently dark comedy as Swann waits for Margot to move the telephone receiver away from her face so he can strangle her. Honestly, lighten the score and it could be something out of a Pink Panther movie.

The halfway point, then, sees the murder attempt having failed — with wonderfully subtle irony, in part because of Tony’s best laid plans — and brings in Chief Inspector Hubbard (John Williams), whose close questioning and interpretation of the salient facts shows the investigative side of this inverted mystery. Pleasingly, not everything plays out as planned, and Williams invests his inspector with just enough sly asides and Columbo-esque faux-fallibility to make him stand out where he could easily have been bland and forgettable.

The final stretch again plays out almost wordlessly, with Hubbard’s intelligence coming to the fore and a fabulously compact explanation of the reasoning that had brought us to this point, a piece of pure Golden Age brilliance that wows precisely because of how simple it makes the complex seem. My memory was that this ended with Milland silhouetted in the doorway, but he’s allowed a moment of urbanity that seems to betoken so many Hitchcock villains — and which brings James Stewart even more to mind, though I doubt he’d ever have played a bad guy — and then we depart with a minimum of fuss and fanfare. They really don’t make ’em like this any more.

Dial M for Murder is possibly best-remembered these days as an abortive early attempt to utilise 3D technology at the cinema, but it’s pleasingly free of too many gimmicks along that line — the occasional piece of odd framing seems to supply the most likely moments — and instead stands on its own for the intelligence of its plotting and the density with which Frederick Knott’s script (from his play of the same name) fits in its various, immensely clever reversals. Hitchcock made showier films, but it’s no surprise that he could turn his hand to the Howcatchem so readily — the suspense that was his trademark is tailor-made for this sort of setup, and the film’s stagey background allows the viewer to really immerse themselves in what is, after all, really a masterpiece of how to use one location and a handful of people in such an engaging way.

When I first watched this, I failed to appreciate the cleverness of the inverted conceit, but with age and more experience I now love the canny reasoning here even more. It’s telling that this is the sort of crime film Hitchcock would return to over the course of his career, dipping his toe into the whodunnit arguably only once — To Catch a Thief (1955), which would again see him working with Kelly. The Master may not be on top form here, but the slight blandness of the direction is more than made up for by a tight script, strong performances, and the good sense to get out while the going is still good. Great fun.

I also watched it a long time book and your review makes me want to rewatch it. I have seen a Hindustani version of it too: Aitbaar (Trust). That too was good and well enacted.

LikeLike

I have probably seen this more than any other Hitchcock movie, it is incredibly compelling.(For some reason it was shown on Italian TV a lot in the 1980s). However, don’t fall for the old saw that he didn’t really make any whodunits – he made several. Other than THIEF, the following are all traditional mysteries with a surprise villain unmasked in the finale:

MURDER! (1930)

SPELLBOUND (1945)

STAGE FRIGHT (1950)

PSYCHO (1960)

And REBECCA is pretty darn close!

Like THIEF, all adapted from previously published novels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Consider me duly chastened and that opion revoked 😔😁 Though Psycho ad a whodunnit feela like a bit of a reach, I had forgotten Stage Fright. Mea culpa.

LikeLike

PSYCHO is 100% a whodunit, one with with Gothic horror window dressing.

LikeLike

Well, them’s fightin’ words 😄😄

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll get my Mum to convince you 🤣

LikeLike

In 3-D, it’s mostly a reminder of how much of a stage play this is, although there’s a nice jump scare during the murder attempt when Margot reaches for the knife and plunges it in Lesgate’s back. I love John Williams in this! Everyone is good, except for Bob Cummings, who is too old and rather boring – but in all fairness, it’s a boring part! It’s a good film, but there are about thirty-five better Hitchcocks to watch!

LikeLike

No doubt better Hitchcocks exist, but I have to work with what I can get for free 😄 Still want to rewatch Rope, and now Sergio’s got me doubting my opinion of some borderline Hitchs, so we can expect this to be an increasingly occasional feature of the blog going forward.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll email you Jim, if you want to borrow some DVDs etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of my all-time favourite films!

LikeLike

I loved revisiting it. Looking forward to rewatching more Hitchcock over the years ahead.

LikeLike