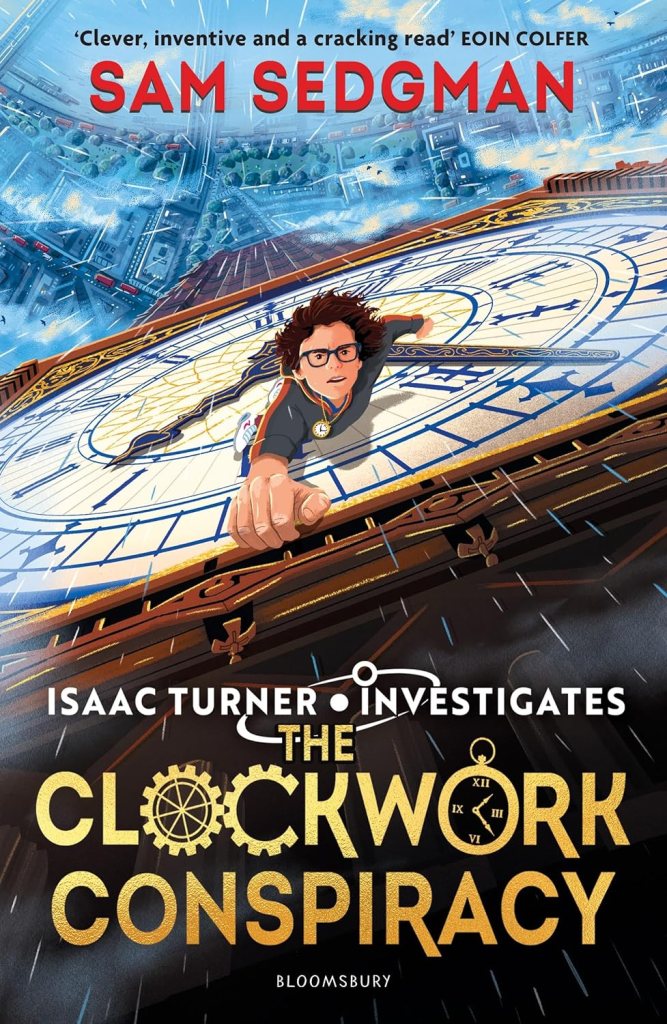

Having co-written one of the great modern crime and detective series of books for younger readers, Sam Sedgman ventures out on his own for the first time with The Clockwork Conspiracy (2024). So let’s have a look, eh?

Our teenage protagonist this time around is 13 year-old Isaac Turner, whose father Diggory is the Keeper of the Great Clock at the Palace of Westminster — “the one everyone thought was called Big Ben, but wasn’t”. On the night that the clocks go back, the two ascend to the top of the clock tower to adjust the time, only for Diggory to vanish in borderline-impossible circumstances. How to explain this vanishment? And how is it linked to the New Time Bill being debated in parliament, which seeks to decimalise time, bringing us hundred-second minutes, hundred-minutes hours, and ten-hour days?

The most impressive achievement of this fast-paced and very entertaining book is how Sedgman takes the concept of time — something we encounter every day without really thinking about — and turns it into a compelling MacGuffin at the core of his story. Where so many books rely on something far more concrete — finding a killer, saving the community theatre — it’s no small achievement to take an abstract concept that we’re fundamentally used to ignoring our whole lives and to make it feel as urgent as it does here.

Interestingly, the concept of the decimalised New Time is presented both as the revolutionary step of a forward-thinking nation and a pointless piece of political manoeuvring that’s really not going to be the panacea that it’s presented as:

“That’s what got him elected Prime Minister: he promised the country would be transformed.”

“And will it be?” asked Hattie.

“It might,” said Miriam with a shrug. “But mainly it’s a distraction to make everyone feel like the government are doing something to improve the country. It won’t help us build houses or railways or make it easier to see a doctor. But that stuff’s harder to sort out. It’s much easier to sell the country a dream.”

Any post-Brexit parallels are, I’m sure, entirely imagined.

The pace is kept fast as Isaac and his new friend Hattie — daughter of the Speaker of the House of Commons, and possessor of a map that enables them to clamber over rooftops and through various secret entrances — ricochet through codes, cabals, and criminous endeavours in order to find both Diggory and other associates who have similarly vanished in recent weeks. It’s a bit of a shame that there aren’t traditional clues in the manner that made the Adventures on Trains books so much fun, but two intelligent teens forging their way to the heart of a conspiracy is still a pretty enjoyable time, reminding me of The Da Vinci Code (2003) by Dan Brown, except the scientific lectures are interesting and believably inserted into the plot.

Indeed, in keeping with The Da Vinci Code, Isaac and Harriet are pursued throughout their investigations by an apparently unstoppable white-haired man who is clearly acting on the orders of an unknown villain whose identity will be dropped as a third act twist, and Sedgman does very good work in making this harbinger of menace more than simply a muscled and fanatically-driven cipher. With his seemingly-unquenchable desire for tidiness, Caleb becomes more than simply a goon and emerges as perhaps the most interesting character in the whole narrative. And, given his relatively brief page time, it speaks volumes bout how the effort to slightly round out your minor character can really pay dividends.

There is also the small matter of that borderline-impossible vanishing, which I’m not sure quite qualifies as an impossible crime — minor spoilers: when someone says (rot13) V’ir ybbxrq rireljurer…they haven’t — but does solid work, as you’d expect from Sedgman, in establishing the apparent insolubility of the problem due to a lack of feasible options to explain it:

“He didn’t come down the stairs, and he wouldn’t bungee jump off, abseil down the side or climb into a helicopter.”

It’s solved by Isaac in a moment of revelatory insight which, while clever and within the reader’s grasp — Sedgman is to be commended for the fairness of getting the relevant knowledge onto the page to seamlessly — doesn’t quite qualify in my mind as clewing because the deduction Isaac reaches doesn’t necessarily result from the realisation he has. Yes, I’m no fun. I just want there to be detection in these juvenile mysteries, is all, and Sedgman’s great work alongside M.G. Leonard has set a high bar.

The Clockwork Conspiracy is, then, a fast, fun, and intelligent reads that does great work in reframing something as nebulous as the very seconds that tick past us into vital and important factors of our lives. It’s an encouraging start for a new series, and does well to stand out in the crowded juvenile fiction market. Next up for Isaac and Hattie is The Forbidden Atlas (2025), and no doubt a great time will be had there, too.

Looking forward to this!

LikeLike