On the day that a child is born into the ancient, vast Swift clan, the family Dictionary is placed before the new mother and, with her eyes closed, she opens it and runs her finger down the page until it settles “on the word and definition that would become her child’s name”. What Beth Lincoln chooses to do with this intriguing idea in her debut The Swifts (2023) is…a little confused.

The essential conceit of this book — huge ramshackle family pile, a reunion that brings all the branches of the diaspora together to search for a long-fabled Hoard of jewels and riches, murder resulting — is both classically-styled and entertaining. Lincoln has a good eye for the shop-worn tropes of second rate murder mysteries (potentially-sinister overheard conversations, obscure happenings, everyone rounding on ‘the outsider’), and the steady deployment of these lends proceedings a Victorian air that suits the rambling mansion of the setting. When the library is full of books that might be triggers for deadly traps (“detective novels were some of the only books in the library not booby-trapped (they were considered educational)”), it’s fair to say that fun is going to be had.

And, for the most part, The Swifts is fun. Lincoln exhibits a superb turn of phrase that wrings a sense of joyful creativity from some remarkably mundane actions (“[she] learned what it sounds like when a great many heads swivel round at once, which is similar to a cat skidding on a roll of taffeta.”), and the various levels of cruelty exhibited towards the various Swifts by their distant kin are captured piquantly — like siblings Atrocious and Pique telling young Felicity that she “might even see your designs in a department store one day”, or the “weaponized politeness” of a conversation had in archly condescending tones. The wider world of their unknown relatives crashing in upon sisters Shenanigan, Phenomena, and Felicity isn’t entirely pleasant for them, and the adventure that results is tinged with the sense of caution that young people invariably feel around unfamiliar adults.

When matriarch Aunt Schadenfreude is shoved down a set of stairs, Shenanigan and Phenomena begin, in their own peculiar idioms, to investigate who might want to commit a murder and why.

“Gosh, murder is fun! I mean,” she added hurriedly, “of course it’s terrible that Aunt Schadenfreude is hurt and that everyone’s so upset, but I so rarely get to do anything interesting.”

Woven through this, quite boldly for a book aimed at this target market, is the idea that perhaps wealthy people aren’t the most morally upright individuals, as old money has usually come from some shady dealings (“The Hoard is made of gold and silver, yes. But it’s also made of textiles and tobacco, mines and machinery, spices and blood. The history of our Family…is one of heroism, intrigue, adventure. But it’s also one of deceit, and theft, and plain old nastiness.”). Equally, the idea that present generations are in part responsible for turning a blind eye to the unsavoury aspects of older behaviour is cleverly dropped in (“If [he] was so terrible, why is his monument still standing?”), though, given the number of irons in the fire, such thrusts will doubtless go over the heads of most younger readers.

Because, see, this is quite a busy book, as perhaps befits a debut, and — ironically for a book with this title and a fixation on nominative determinism — there’s a sense of wasted space at either end because of the sheer number of things going on. This is easily exemplified by the “inciting incident” of the attack on Aunt Schadenfreude happening a third of the way in and the perpetrator being unmasked with a quarter of the book to go…some trimming would easily have been possible at either end, and then this might live up to its promise more resolutely.

The mystery, too, is a little undercooked — arguably deliberately, given the various murders that result — and it’s a shame to see it resolve as it does, the clues turning out to be mostly valueless, the killer giving themselves away by action rather than being reasoned out by our junior detectives. It entertains, no doubt about that — “Scrabble — to the death!” — but it reminds me of The Secret Detectives (2021) by Ella Risbridger in that much of the sound and fury of the events in the book end up signifying very little indeed. The tropes are well-observed, as mentioned, but part of observing them is to then plait them into a pattern that explains them away, and here that pattern stretched credulity, implying that the tropes were included only because they should be in a mystery novel. That’s…backwards, to my way of thinking.

I’m also not at all sure what the nominative determinism element brings to proceedings. There’s a clear narrative seam of the importance of finding your own character and voice, which is a crucial message for younger people, but while the majority of the Swifts live up to their names (Phenomena is interested in science, Gumshoe is an old-style private detective who literally narrates his way around the house, Pique and Atrocious exemplify those traits admirably, Inheritance is the family historian), others veer so wildly off-piste (Candour is a doctor who…loves synonyms) that it feels a good 30 pages could have been cut by simply never making a reference to the naming thing in the first place. Maybe that’s the point? I dunno.

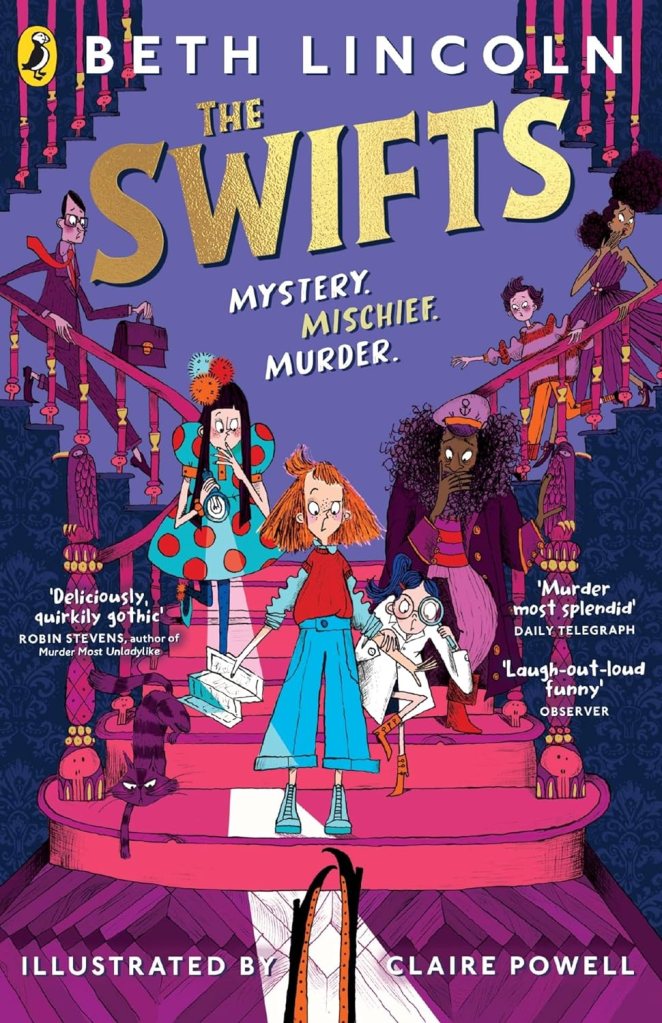

All told, I’ll remember The Swifts for the atmospheric writing (“Now that the guests had arrived, the thick oak front doors had been propped open, and the House took great gulping breaths of people, sending them scudding between the Billiards Room, the lounge, and the far side of the hall…”) and playful scene setting than for any of its plot mechanics or, disappointingly, the characters that bounce around within it. Claire Powell’s beautifully anarchic illustrations do much to bring this to life, and are responsible for many of the impressions I’ll carry with me…but, hey, I’m not the target market, and I can well believe that any 10 year-olds in your life will hug this to their hearts for a long time to come.

Somehow the names (or nick names) make it feel as though the author was trying a little too hard.

LikeLike

It’s an interesting concept, but I can’t help but feel a little disappointed with what is — or, indeed, isn’t — done with it. Younger readers will appreciate the wordplay when they realise what’s going on, but, yes, maybe there’s a little too much straining and not quite enough reason behind it.

LikeLike