![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

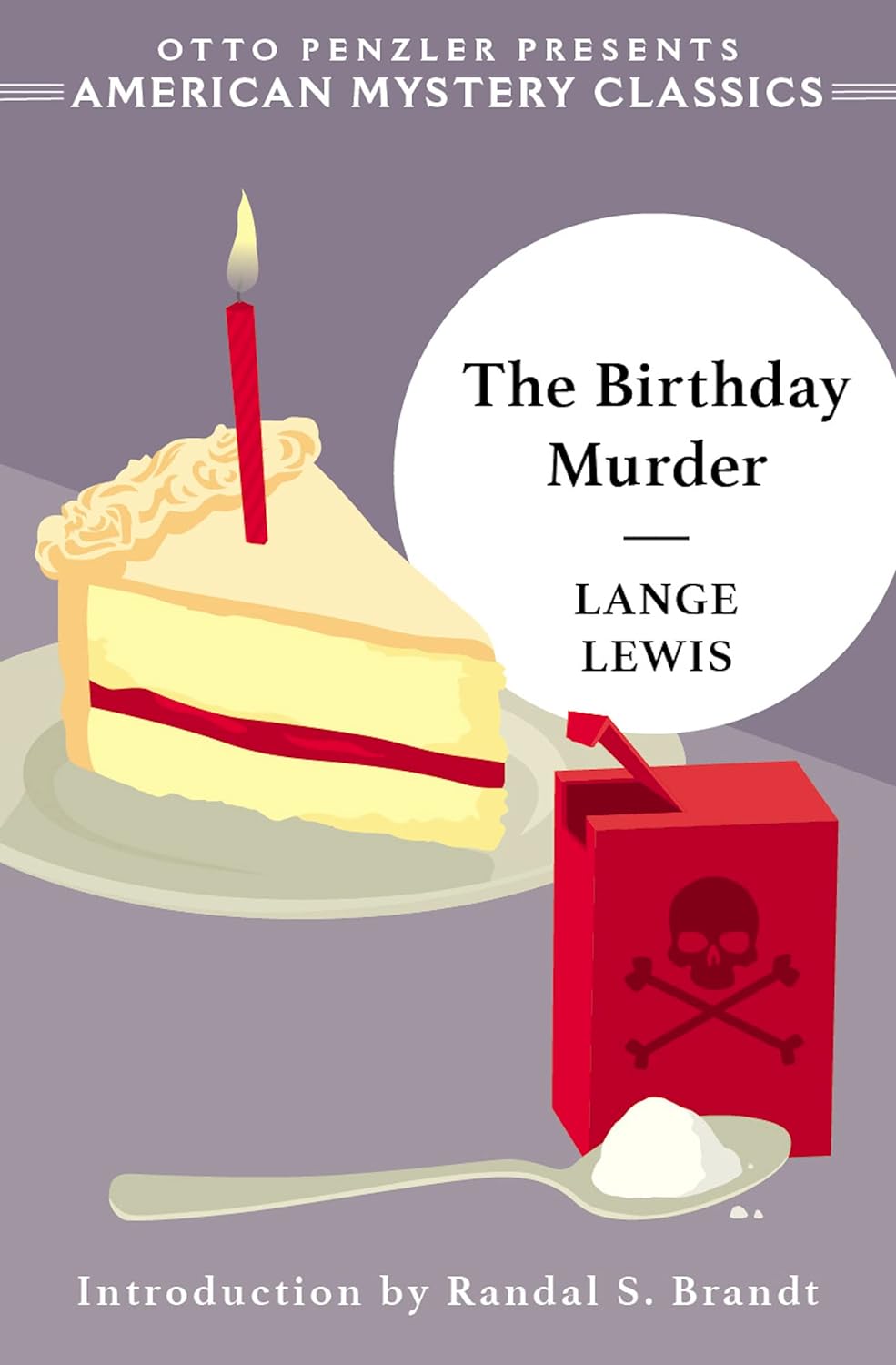

Having researched and written a book in which a woman poisons several people, Victoria Hime inevitably ends up as the prime suspect when someone close to her is poisoned by the same means. The fact that several people came and went from the Himes’ house on the day of the poisoning is the only light offered to Los Angeles detective Lieutenant Richard Tuck, but while the method remains clear there’s the small matter of opportunity and motive…all of which keeps swinging back to Victoria, the case against her “signed, sealed, and delivered” at almost every turn. Except we, the reader, know she didn’t do it…so what really happened?

The Birthday Murder (1945) by Lange Lewis seeks to make plenty of hay from this deceptively simple setup, and has about it the genuine ring of Agatha Christie’s more tightly-focussed puzzlers like Five Little Pigs (1942) and Crooked House (1949). And, like Christie, Lewis finds something interesting to do with the solution even if she doesn’t quite maintain that level of interest throughout. Much like an impossible crime novel in which the setup is so damn perfect that only one, frankly obvious solution is possible, Lewis struggles to find much ground for Tuck to go over, with little in the second half of this novel adding to the clever thinking of the first.

Lewis is at her most successful in the various relationships Victoria maintains with those around her: the comfortable success of her second marriage to film producer Albert Hime after the torpedoing of her first marriage to the rakish Sawn Harriss…whose own shortcomings are communicated with devastating acuity:

He was writing a novel about the scion of a wealthy New England family who revolts against the environment in which he was born and throws his lot in with the workers of the world. In Greenwich Village at that time there were not more than three other young men writing this same story.

The reappearance of Sawn is arguably supposed to be an inciting event, with the war having matured him from the self-conscious rejection of his family’s wealth to something more of an attractive man of the world, but for all his apparent animal magnetism I couldn’t get a Brian Fantana-level of sleaze out of my head whenever Sawn — god, it’s such an annoying name — was on the page. Perhaps slightly more interesting is Bernice Saxe, an ageing glamourpuss who seeks consolation in the arms of younger, less suitable men and whose own character arc when it comes to saving her marriage is as frightful and selfish as we would expect given how well Lewis draws her.

Mix in the young actress Moira Hastings, who is keen to secure the lead in the film version of Victoria’s book that Albert seems likely to produce, and who Victoria feels is too unworldly for the role, and there are really only so many places you can move this tiny cast to before it starts getting a little tedious. I was reminded of The Alarm of the Black Cat (1942) by Dolores Hitchens, also reprinted in the American Mystery Classics range, in that there’s once again a core idea and setting here which is superb, but the book is held back by a singularly linear central plot to which little in the way of complications is added. The best practitioners of the American school (Anthony Bucher, Craig Rice) were able to plot in a good, complex-yet-clear manner, and it’s a shame that someone who writes individual sentences as well as Lewis can’t operate at the same standard.

That plotting becomes important in the final stretch, too, when, after much repetition, the crime — and notice how I’ve not told you who the victim is, something mentioned both in the synopsis and the introduction which I maintain you’re better off not knowing — pinned in a surprising direction but with little by way of proof. Hell, Victoria even tells Tuck that he can’t actually be sure she’s not the murderer and he agrees with her, despite a bunch of exposition at his first appearance pointing out how damn careful he always is to be certain in his cases:

He seemed careless of achieving a record for speedily winding up cases in which he was involved, and showed instead a disinclination to make an arrest without substantial evidence. The result of this odd quirk was that no case of his which had come to trial had ever been lost by the state. This gave him a definite standing with Gufferty, the head of the Homicide Squad, and, which was more important, with the District Attorney’s office.

This, then, comes just about recommended for the surprise it’s able to spring in the final stretch, but I’m inclined, given Lewis’ small output, to imagine that she’s at best a second-stringer where the matter of mystery fiction is concerned. It’s an intriguing proposition as a book, but I’d be more favourably inclined towards if it Tuck’s much-vaunted rigour played the part you are led to believe it will — he’s the series character, after all, so the idea would surely be to see him at his best. This is very well-written, offers an interesting perspective on murder, and will pass a few hours very admirably, but a forgotten classic of the genre it most certainly isn’t, despite the good ideas at its core.