![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

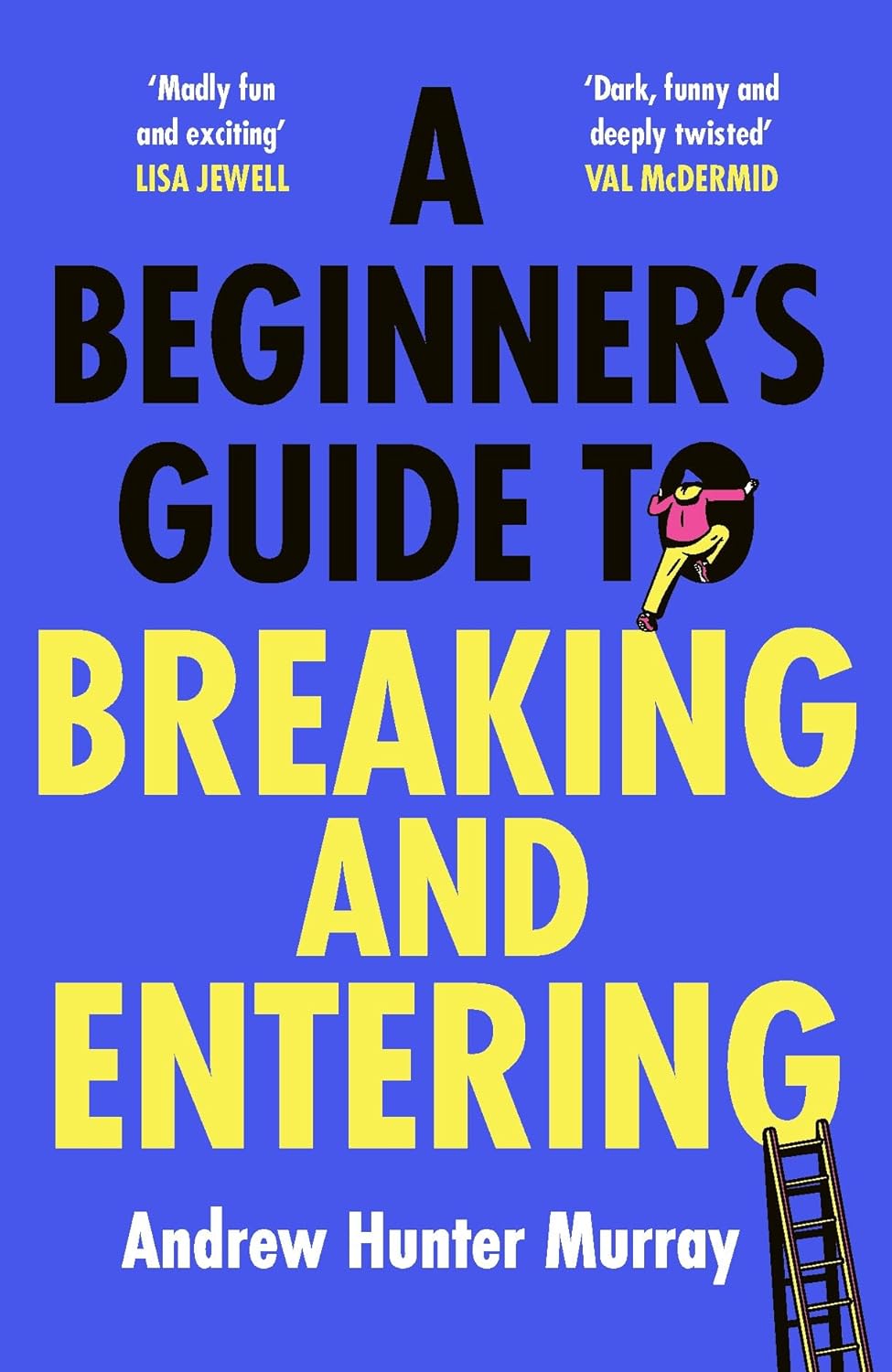

Shirley Ballas. Richard Coles. Susie Dent. Richard Osman. Robert Rinder. These days, if you want to publish a crime novel, it clearly helps to be a UK media personality. And why not? Publishing’s an uncertain business, and an existing following should hopefully convert into sales — good luck to them, I say. Add to the above journalist, podcaster, TV-version-of-his-podcaster Andrew Hunter Murray, whose third novel, A Beginner’s Guide to Breaking and Entering (2024), finds him crossing into the sort of genre territory that captures my attention. And while not perhaps leaning as hard into logical reasoning as I’d prefer, there’s much here to enjoy.

We start with our narrator Al — not his real name — in prison for the crimes he has committed in the coming narrative:

[T]he story I set in motion is prompting quite the kerfuffle out there. I’m not surprised, really. Any story featuring luxury property, big-money fraud, international espionage and high treason will snag the attention of even the thickest newspaper editor.

Al, we learn, is an “interloper”: an essentially homeless man whose chief occupation is breaking into the vacant second and third homes of the uber-wealthy and living there in their absence. He doesn’t steal anything, he’s not motivated by any sense of social imbalance or political ideology — he just likes nice houses, and so stays in them, moving on after a couple of weeks without (he hopes…) the owners ever being aware that he had been there.

When chance brings Al into contact with sisters Em and Elle and their friend Jonny, three young people who do pretty much the same thing as he does, the four of them team up to break into a lavish country dwelling…only for the house not to be quite as untenanted as they’d thought and an unseen visitor to arrive and murder the occupant. And so, knowing their DNA and fingerprints are all over the place, and their faces will be on CCTV in the local pub, they go on the run: hiding from the police and the enemies the dead man appears to have made on the other side of the law, figuring that only in catching the killer can they clear their names.

The book is, honestly, a lot of fun. Murray has a superbly gentle way with his comedy, which creeps into the cracks between the multiple considerations that make a modern crime novel far more involved than its 1930s equivalent — not merely the existence of CCTV, say, but also the fact that you can’t just go to the pub and delete the CCTV footage because the company who provides the service backs everything up on an overseas server — and catches you with some wonderfully natural surprise turns:

“We must have scared the killer off when he was at the door, but by now he might have—”

“Or she.”

“What’s that, Jonny?”

“The killer. You assumed it was a he. Could have been a she.”

“Thanks, Jonny. Always good to get a lesson in everyday sexism from an unexpected angle.”

You have to swallow a few unlikely developments, like Jonny being a human Swiss Army Knife who can hack and bodge anything going, but the truth is that the investigation undertaken by these very amateur detectives is well-developed and, pleasing my Humdrum-loving soul, runs down many false trails on the way to maybe possibly hoping to get a step or two closer to the solution. The book is probably 70 pages too long, but I devoured it in two long gulps, because it’s so very entertaining and manages to juggle the shades from ‘outright humour’ to ‘violent menace’ very well. Not reading much in the way of contemporary fiction, it’s interesting to see the little touches that make this very much a 2024 novel, too, like the post-COVID ubiquity of face masks. That’s probably already a crime fiction staple, but I liked the repeated use of it herein.

The fault in this really lies in its closing stages, when the result of the investigations is, disappointingly, in no way informed by the events that preceded it. Now, yes, I reckon Murray is purposefully challenging a detective fiction trope here, but I’m also a fan of my detectives actually…detecting. The sudden raft of deductions Al makes in this closing confrontation, which are all clever but don’t feel especially earned, don’t convince me, either: it doesn’t quite fit with his character, and I almost wish these two conceits had been swapped: Al figuring out the first one, and the other being told to him. Because, as it is, you could almost skip 300 pages in the middle and still follow what’s going on at the end, and that’s not the sort of experience I seek. If you’re fine with this, however, add a star to the above and dive on in.

Despite its bland title and a cover so generic that it almost feels like a meta demonstration of Al’s much-vaunted unmemorableness, this comes recommended for the pleasingly harmless tone of its humour (“[T]he lift is so tiny that to see even two people getting out of it looks like a magic trick.”), the occasional sentiment which hits unexpectedly hard (“Maybe that’s how people get over trauma — they just repeat the words until it’s banal.”), and the joyous experience of spending time with this core quartet. Murray’s structuring of the investigation would hint at a very adept mind at work, and it would be great to see him apply this cleverness to a proper detective plot in future. If he writes it, I’ll read it…so watch this space.