![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

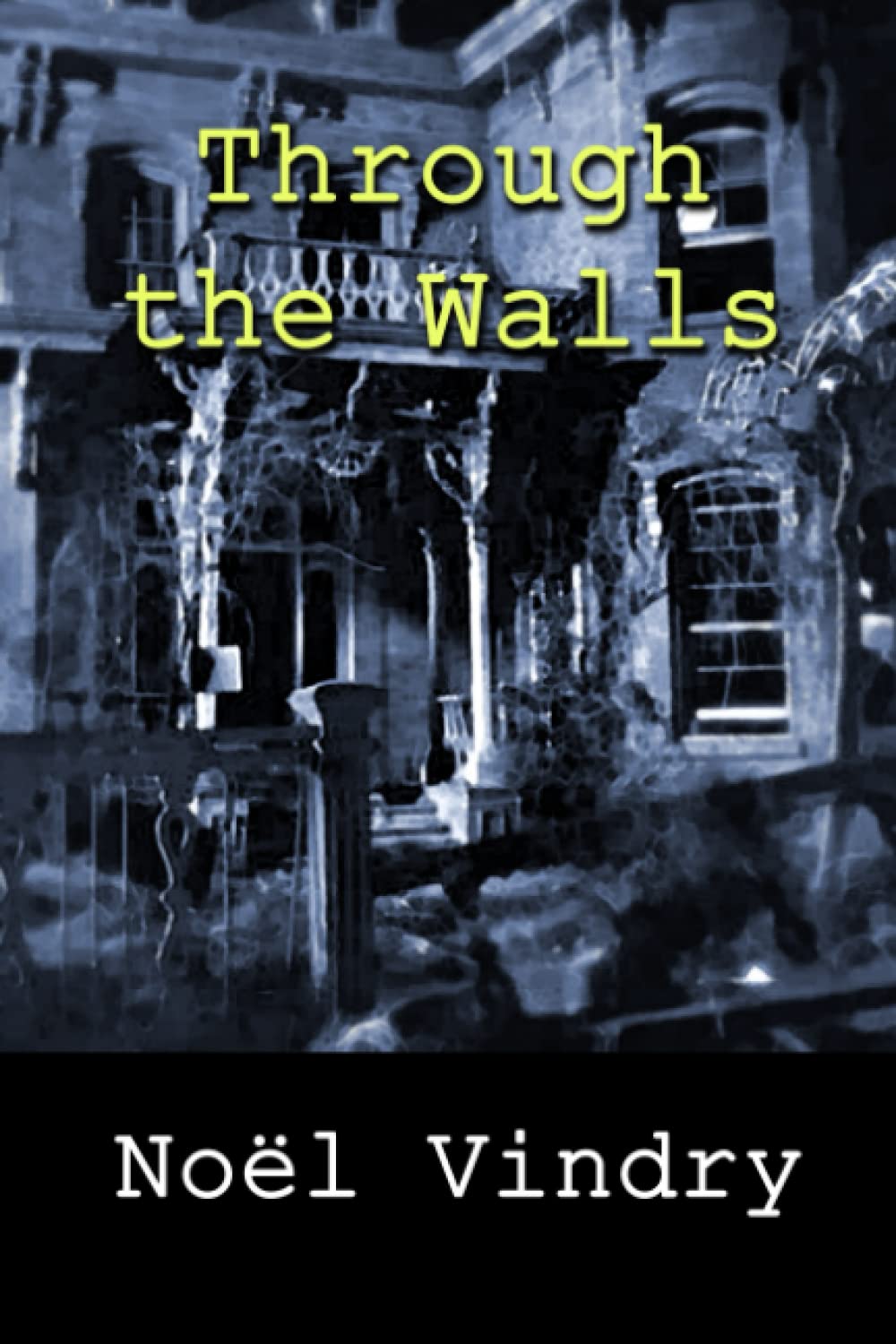

Full disclosure, this is the second time I’ve read Through the Walls (1937, tr. 2021) by Noel Vindry, but I was on blog hiatus at first encounter, so here’s a chance to get my thoughts on record. Similar to The Howling Beast (1934, tr. 2016), this sees Vindry’s series examining magistrate M. Allou consulted by someone who has lived through baffling events, only for Allou to give some meaning to the apparent impossibilities at the end. The setup here is slightly less enticing — someone in apparently breaking into Pierre Sertat’s house at night and searching it carelessly enough to leave things just out of place enough for Sertat to notice — but the patterns that Vindry spins are wonderful, even if not all the answers are as convincing as we’d like.

Commissaire Maubritane is the policeman in the scene in Arles, summoned back by Sertat because he had solved a case in the region a few years previously, and it is Maubritane who must deal with the apparent impossibility of the nightly visitor who manages to make their way in through locked shutters and bolted doors yet leaves the front door unbolted when leaving. And, to Vindry’s credit, Maubritane isn’t one to immediately jump at shadows, instead considering reasonable, rational solutions that bring everyone under the umbrella of suspicion.

“[T]hat’s how we have to proceed: even the improbable can’t be ruled out, and every hypothesis is valid unless it can be demolished by facts.”

A night-time chase of the intruder through the house only reinforces his confusion as to what might be happening, but it is not until murder occurs in a locked room that the fur really starts to fly: someone is shot at close range yet fails to see their attacker, a man appears in a locked room and stabs one of its occupants before vanishing, and a third man is stabbed in a hospital room which has a policeman posted at the door. It’s a veritable cavalcade of bizarre events, and if anyone is able to weave any sort of pattern out of them before M. Allou holds forth at the end then, frankly, very well done to you. Hell, I was so bamboozled at this second reading that the solutions I remembered all turned out to be false, possibly the result of my speculations when I read it first time.

And, to be honest, I’d have liked some of my memories to be the correct solutions. Not just for arrogant reasons, either, because, see, the explanations of most of these impossibilities are rather damp. What saves the book ovrall is the way their compact occurrence occurs in such a sleepy backwater — a triumph both of character intelligence and plotting acumen. I really can believe that such a pattern would elude explanation, and while it requires a few credulous leaps on the part of the investigating police, the way events rush in upon the coat-tails of an already magnificent array of fabulous occurrences does bludgeon the mind until you start to wonder if it might actually be possible to walk through walls…because how the hell else is Vindry going to explain this?

So, while this comes commended for its tight plot rather than its brilliant impossibilities — indeed, I’d probably say the same about all four of the Vindry books John Pugmire has thus far carried over the language barrier — little sparkles of insight or wit show through. Maubritane is a cipher, really, but I liked him more when learning that he was “was very careful not to give his opinion too soon. Ten years in the job had taught him to be non-committal and not to risk his reputation by premature announcements. A thoughtful look sufficed to maintain his reputation for perspicacity amongst journalists”. True, he’s guilty of some shocking reasoning — just because someone has been shot with the same gun, it doesn’t mean they were shot by the same person — and is mostly there to observe events so that he can relay them to Allou, but as an ostensible cipher he’s a perfectly likeable protagonist.

In the grand tradition of French mystery fiction from this era — something I can only hold forth on with any confidence because of Pugmire’s tireless efforts in bringing us classics in the genre for more than a decade — Allou’s solution comes about with zero detection, instead resulting from a sort of thought experiment where he happens to hit upon the correct interpretation every time. I’d definitely have enjoyed this a little more if he occasionally ran down a false trail in those closing stages to show how reasoning should be applied, but it’s a small gripe. And it almost feels unworthy to gripe on those grounds given how hard a time Vindry doubtless had making any of this make as much sense as it does.

A flawed book, then, Through the Walls is another fascinating window on the history of the European classic mystery. I’d be interested to know if the inconsistent censoring of rude words — we have “b*gger off” at one point and then “taking the piss” later on — is a direct transliteration, but I’d be more interested in further Vindry translations to see how else he applied himself to this wonderful subgenre in the twelve locked room novels he wrote which Pugmire mentions in his introduction. Even if we’ve seen the best of him, I’d still love to read more; he may not always convince, but he certainly exerts a fascination that is hard to deny.

~

Noel Vindry on The Invisible Event; all translations by John Pugmire

The House That Kills (1932) [trans. 2015]

The Howling Beast (1934) [trans. 2016]

The Double Alibi (1934) [trans. 2018]

Through the Walls (1937) [trans. 2021]

“…this comes commended for its tight plot rather than its brilliant impossibilities”

Agreed. This story should have never been presented as a parade of impossibilities, but, as you described it, a veritable cavalcade of bizarre events without a hint of the impossible. A why-would-they-do-that? The last chapter clarifies Through the Walls is not intended as a detective story of tricks and ideas, but as a demonstration of Allou’s system by supplying simple, straightforward answers to a string of utterly bizarre incidents. But leaving readers hanging until the last chapter before telling them it’s not really impossible crime story will probably result in a few books and e-readers getting tossed across the room in disgust.

I’m keeping my fingers crossed for a translation of Pierre Boileau’s Six crimes sans assassin.

LikeLike

The lack of Boileau transalations following the B-N titles which Puskkin put out a few years ago makes me suspect that something might be tricky about those rights…but, yes, 6CsA in English would be a delight — we can but dream 🙂

LikeLike

Indeed, I once asked John Pugmire about this and he said it was purely a rights issue. Apparently the French publishing house that owns the rights refuses to work with print-on-demand publishers.

LikeLike

Interesting; what a way to not move with the times!

LikeLike

Thanks for the review Jim – I haven’t had read anything by Vindry yet, sounds like I might enjoy “Through the Walls”. Just had a quick online search to see if any of this author’s books are readily avalable in French and couldn’t any. His stuff’s that scarce, huh.

LikeLike

This…might not be the Vindry to start with. I’d suggest The Howling Beast, which is the best of the translations to date,

As to his scarcity, yeah, it seems the guy’s pretty much forgotten in France, so what chance does the rest of the world stand?

LikeLike

This one earned a meh from me. Too much lying and too many coincidences.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s all difficult to get around — but the intelligence behind some of the reasoning the characters do makes up for that to a certain extent — a certain extent, mind.

LikeLike