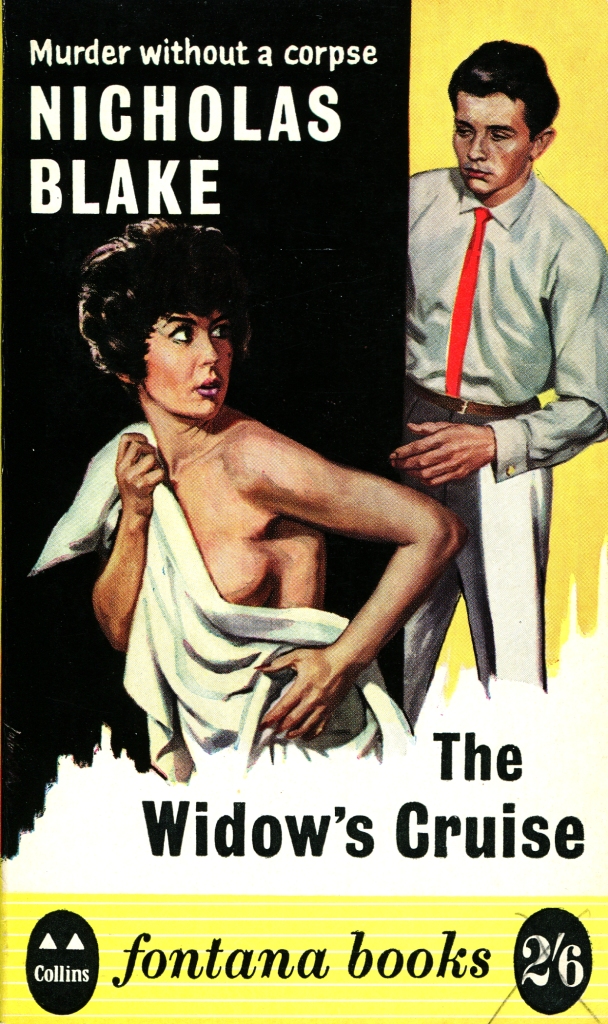

Nicholas Blake is hardly a dusty and forgotten member of detective fiction’s past, but my experiences with him to date have been so lacking in high spots that the only way I’m going to read The Widow’s Cruise (1959) is by screwing my courage to the sticking place as part of this Mining Mount TBR endeavour. And so here we are.

Professional amateur sleuth Nigel Strangeways is getting away from it all, taking a cruise on the Menelaos around some Greek islands, accompanied by his sculptor friend Clare Massinger. It will be a chance to relax, to mix with their shipmates like the garrulous Ivor Bentnick-Jones, scholar of the Greek classics Jeremy Street, and the Bishop of Solway and his wife. Little does anyone suspect the difficulties which will be sown by the arrival of sisters Ianthe Blaydon and Melissa Ambrose — the former is recuperating following a nervous breakdown and has done enough to put up the backs of at least three passengers before even boarding, and the latter is a femme fatale widow in the classic mould who will have men dancing to her tune for her own amusement…even if her charms do seem to cease at surface level…

Melissa Blaydon had very little, it seemed, inside that beautiful head. Her animation was artificial, her conversation that of a woman who has had her thinking done for her by others. It consisted largely in name-dropping and an enumeration of the places she had lived in and visited. Did they know Cannes well? Were not the shops in Rome absolute heaven? Capri had been ruined since Farouk went there. Greece, for Mrs Blaydon, was chiefly distinguished as the birthplace of the Onassis brothers.

The first half, then, is dedicated to the various personages on board mixing, rubbing each other up the wrong way, and generally giving as much space as possible to seemingly innocent actions which will be deemed suspicious later — as classically-styled a murder mystery as you could imagine. Everyone is followed about by the vexing, 10 year-old Primrose Chalmers, whose lay psycho-analyst parents come in for the sharper edge of Blake’s pen, teenage twins Faith and Peter Trubody make much hay from their unpleasant association with their former schoolteacher Ianthe, and Blake seems to enjoy himself in the relaxed atmosphere of shore leave and donkey rides:

[Nigel] eyed his own animal with considerable misgiving. It seemed several sizes too small for him, and it had a distrait yet purposeful look in its rolling eye which reminded him of the wrong kind of society hostess.

It’s far from gripping, but it would take a hard heart not to enjoy this calming, meandering setup, sprinkled with charming observations like Peter Trubody complaining about something “in the exact tone he would be using thirty years later in his Club to inveigh against the enormities of the Budget”, or sharp notes like Jeremy Street, indulging a shipboard infatuation, growing suddenly weary of “these yearning females and their pathetic, pseudo-literary talk”.

Cometh the halfway point, cometh some murder — one of the above being found drowned in the ship’s pool and another vanishing, apparently jumping or being thrown overboard. Strangeways, by deign of his association with Scotland Yard, finds himself entrusted with the unenviable task of unpicking what has happened and why, and just which of the foregoing events have any bearing on this sudden outbreak of violence.

And it’s at this point that the wheels, for me, came off.

Certain interesting revelations are achieved through Strangeways’ interviews of the passengers, but said revelations are only achieved through interviews — interminable, endless interviews in which people tell you a lot of what you’ve already seen and, in one case, reveal a naivety which will see at least one of them buying a London landmark over the phone if they ever acquire enough money. You admire Blake’s willingness to declare all the relevant clues and information — in terms of fair play I cannot fault this at all — but the skill of the detective novelist arguably lies in giving your reader the information to come to the correct conclusion ahead of time without making it bloody obvious that you’re doing so.

Additionally, the reasoning used herein is faulty in several key ways. To draw an approximate parallel, it reminded me of the egregious laziness of A Smell of Smoke (1959) by Miles Burton — published, as sheer, cussed happenstance would have it, in the same year — in which a man in known for smoking an especially pungent brand of tobacco and thus, when the tobacco is smelt at a crime scene, falls under suspicion for the crime (for, like, most of the book). Here, an entirely innocent action with a perfectly serviceable explanation is taken as a jumping-off point for a piece of realisation that, while possible, simply doesn’t hold in the realistic world this novel has tried to present. The genre has repeatedly, almost to the point of tedium, shown itself to be significantly cleverer than this, and it’s at such moments that I feel Blake is only given a pass as a writer of detective fiction because in his normal life he was the accomplished author and excellent poet Cecil Day-Lewis.

This, however, is not the book’s biggest problem.

Bafflingly, Blake’s central plot repurposes the same key workings and explanation of a novel which did this before, in almost identical circumstances, a mere four years earlier. And I’m not suggesting for a second that Blake is guilty of conscious plagiarism — it’s distinctly possible he had this idea years before, independently of that earlier book — but it seems hugely unlikely to me that Blake could have been unaware of that book (the author is…quite well known in the genre, and someone at his publishers would easily have awareness of them) and massively unfortunate that he still went ahead and wrote this so soon after it already being done. Admittedly, Strangeways goes about revealing the solution in a very different manner, but different delivery alone doesn’t justify so beat-for-beat a similar plot.

The book also ends weirdly, with the crime solved and then another 15 pages of chat to tidy up the myriad loose ends lying about the place, giving the closing stages a frantic and haphazard air that stands in stark contrast with the intelligent calm which (mostly) precedes it. Again, there’s that lack of artistry: you know things not because a clever confluence of events brings them to your awareness, but because you sit on a character’s shoulder while three people discuss, at great length, everything that happened, who it happened to, why it happened, and what else might have fallen out. For a man who had such a superb ear for the English language when it came to his other writing, Day-Lewis really does, to my eye, lack sophistication and plotting acumen in his genre fiction.

I finish The Widow’s Cruise with an increased appreciation of Blake’s contribution to the genre, but also a firmer sense that I could not read another word he wrote and not miss out in any way. This is an easy, breezy read which is more successful in its setting than its plotting, and has more to say about the way people interact than it does about the actions those interactions inspire. Maybe I’ll find more joy in him 30 years from now when I’ve read everyone else — I’d love to, since that would give me another 15 or so novels to dive into in my dotage — but, for now, I think I’ll get on with reading everyone else first.

As the odds of reading this book are very unlikely, would be appreciated if you could give the name of the copied book in rot13? Much appreciated!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gbhe qr Sbepr, ol puevfgvnaan oenaq

LikeLike

Jung ur fnvq!

LikeLike

I have a few Nicholas Blake books, including this one, on my TBR mountain. I haven’t seen many favourable reviews of his work so have not made the time to try Blake. After reading your reaction above, I can’t say I am in a hurry to do so with so many other great books competing for my attention.

LikeLike

Blake’s one of the best. https://grandestgame.wordpress.com/list-of-authors/nicholas-blake/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nick – thanks for recommending Nicholas Blake (Cecil Day-Lewis). I just finished Thou Shell of Death based on your recommendation as well as that of TomCat and Kate respectively.

Clearly Day-Lewis’ intelligence and literary background shine throughout his prose. I don’t have his body of knowledge so didn’t understand always his referent and literary allusions. That didn’t diminish the book for me though.

The impossibilities serve a minor part of the plot, but each one as well as Strangeway’s unraveling of O’Brien’s past held my attention and kept the story moving. The puzzle was clever and the end reveal was a surprise.

I will return to Blake in the future and have Abominable Snowman and Beast Must Die also on the big pile.

LikeLike

I feel the same, and I’d like to be more enthusiastic about what he has written if only because it would mean another author I could love and have plenty of years to enjoy reading. But, well, not to be at present. Maybe in a decade or so…and, yes, with so much else clamouring for my attention, I’m happy to move on for now.

LikeLike

I think by this stage Blake’s heart went out of his detective fiction writing – I find the books after the first 5-6, increasingly pedestrian and the final Strangeways book is just creepy and not in a goosebumps way. I’m guessing you’ve not enjoyed the earlier books, but I think plot wise they are his most creative.

LikeLike

I’ve read this, The Beast Must Die, Thou Shell of Death, The Case of the Abominable Snowman, and A Question of Proof. I found them all…fine. But when five books have failed to elicit little more enthusiasm than that, it’s clear the author doesn’t work for me.

I heartily expect to fall in love with Blake and Michael Innes in due course. After all, I find a lot more joy in Chesterton these days, so anything is possible…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’ve given him a good try and covered some of his best works, so he might not be for you. Innes is that sort of author for me – after 12ish reads – there was only one which I thought was great. The others were meh or ugh.

LikeLike

Aaah, yes, the famous Innes Meh Ugh Scale — a classic of genre criticism 🙂

LikeLike

Very rich for Blake of all people to comment on anyone having “pseudo-literary talk”, let alone his own characters. I’m not sure he’s read his own writing…

Anyway, if you can’t tell, I’m of the same mind as you re: Nicholas Blake. He’s touted as an author of “psychological mysteries” but the “psychology” is always just Strangeways making observations and then musing about neuroses here and complexes there. Psychology should be demonstrated by the characters at least once, but rather than showing us the characters behave in ways that reflect their psychology, it’s always spoon-fed to us with stupid shit like “the way the man’s books were arranged was indicative of his inferiority complex”. The antithesis of “show, don’t tell” because he sure seems to have a lot of ideas about how his characters’ minds work that he’s excited to TELL us, but he sure isn’t excited to… actually write his characters, that’s for sure!

My interests are very low-brow; I am interested in a mystery puzzle, and not in psychology. But by all means you can seek to supersede the puzzles of yester-year with literariness if you so wish, but if you want to be a mystery of character, you still need to write the characters. That is, I’m not interested in psychology, but if you’re going to offer me psychology, at least be good at it… Nicholas Blake is very impressive as a “literary” mystery author who spectacularly fails as both a literary author and a mystery author (because his plots certainly aren’t anything to write home about either).

If you want a mystery of manners that succeeds as both a character piece AND a solid mystery puzzle, Harriet Rutland showed Nicholas Blake up handily in both categories in BLEEDING HOOKS. To this day, A QUESTION OF PROOF stands as one of the dullest and most tedious mysteries I’ve ever read. If I were to make a list of least favorite mysteries, a Blake would surely show up on there somewhere…

LikeLike

Rutland? Really? I thought Bleeding Hooks was pretty damn shallow.

LikeLike

Shallow, perhaps, but she at least had the decency to actively characterize her characters for what little they’re worth — A Question of Proof’s characterization took the form of not much more than an itemized list of personality traits deduced by random and arbitrary details… I’d take Harriet’s two-traits on full display over Blake telling us about eight that aren’t.

LikeLike

I had to give up on a recent mystery novel because every time we met a new character we had a half-page info dump about every single one of their main characteristics — and this from someone who’s already written six or seven books!

I didn’t find this to be that bad, I just find Blake’s construction of his puzzles to be rather pedestrian. His settings are good, and the way he works in criminous schemes shows some insight, but the people, the events, and the manner everything is achieved just does not work for me.

LikeLike

I read this ages ago, and I seem to say that I liked the lifestyle details better than anything else – and indeed that massive similarity to another book does cast a shadow.

I think I like him better than Michael Innes, which isn’t saying much, and keep his books for the occasional reread, but there aren’t any that I’m saying ‘Hey you must read this, it’s great’ ever.

LikeLike

Yes, “I like him more than Michael Innes” is not a high bar to clear for me, either.

LikeLike

I enjoy your writing more than Michael Innes. You’re welcome to use that quote on the back cover of your next novel…

LikeLike

It’s true — Michael Innes does not enjoy my writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many a rave review of The Beast Must Die led me to buy much of Blake’s library. Actually reading The Beast Must Die led me to my first abandoned read – not because it was bad, but because I simply didn’t care. I can’t imagine tackling another book anytime in the future.

LikeLike

I think TBMD might be the best of the Blakes I’ve thus far read, but obviously mileage will vary.

I, too, used to go out and buy multiple books by an author without having read anything by them — heaven alone knows what I was thinking, because then I felt obliged to churn through them even if I didn’t especially enjoy the writing. Thankfully I learned my lesson and got into reading books by authors that were impossible to find — much more sensible 🙂

LikeLike