![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

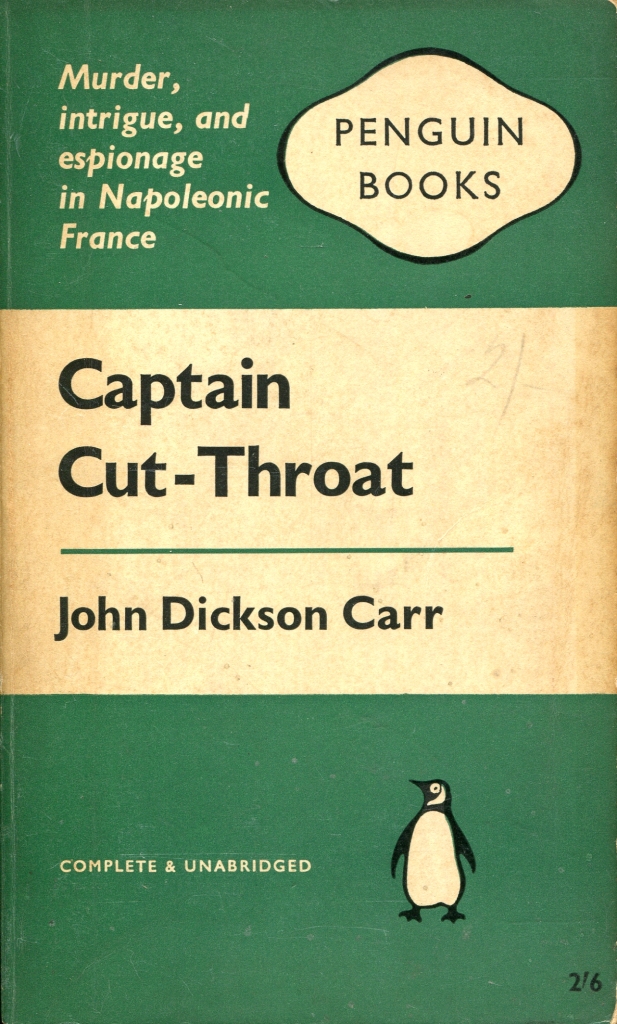

Just as you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, don’t judge Captain Cut-Throat (1955) — John Dickson Carr’s breathless tale of Napoleonic-era espionage and swagger — by its first chapter. The opening to this otherwise very enjoyable story took me three attempts to conquer, as Carr really wants you to know he’s done his research and so crams in too much detail with insufficient focus, leaving me floundering and fearful…a feeling no doubt amplified by my having given up on the two books he published prior to this because they seemed too diffuse to be worth persevering with. Push on, and this soon becomes a propulsive and delightfully plotted romp for the majority of its length.

It is 1805, and French nobleman the Vicomte de Bergerac has been exposed as British agent Alan Hepburn — note to authors, calling your romantic hero ‘Alan’ is not recommended — who, in order to avoid execution by Joseph Fouché, the French Minister of Police, is given an important task: identify the man who, under the name Captain Cut-Throat, is carrying out murderous attacks in French military camps up and down the coast. Napoleon himself has given Fouché five days to accomplish this task, and only in success will Hepburn be set free. So, along with his estranged wife and the lover who betrayed him to the French authorities, Hepburn is sent into the heart of Napoleon’s armies…the same armies who might just be gathering to attack Britain at any moment.

The overwhelming majority of Captain Cut-Throat is a lusty, fast-paced race through 19th century France, with peril positively bristling at every corner. Carr’s characters are pleasingly intelligent both in their realisations in the early chapters which set up the problem and in their actions throughout as plans gang aft agley. Hepburn — seriously, I can’t call him Alan — claims to know the identity of the killer from information provided by Fouché before starting his investigation, and has determined the means of the impossible murder the figure committed without stepping beyond his cell…an impossible murder, incidentally, that you shouldn’t get too excited about, given how low-key the revelation is. Equally, almost every chapter finishes with some sort of cliffhanger, and people must think quickly to extricate themselves from difficult situations over and over again.

It’s also delightfully written, with imagery like a man firing a pistol and obscured from view by “a whole genie-bottleful of grey smoke, conjured form nowhere”, or two people declaring their love for each other with “broken endearments [which] should not matter to a story which concerns men and guns and the map of Europe”. Equally, chapters 14 and 15 comprise perhaps the most thrilling and rousing action scene Carr — hell, anyone — will ever have put on the page, with our hero “scared stiff” and persevering to triumph as the chaos and terror explode around him. This is why the heaviness of that opening chapter galls me so much, because Carr has a genuinely superb eye and lightness of touch for the historical details that enraptured him so in this era of his writing, and when not trying to impress you he’s immensely, almost impossibly, impressive.

The difficulties for me creep in to the final three or four chapters, when a lot of the tension goes out of events and an over-subtle final section seems to be working too hard to provide something akin to the detection Carr’s career had largely been built on to this point. This is a twenty-chapter book that should probably be seventeen chapters long, and then that last twitch at the end of the rope might feel more compelling; but as it is the expertly-maintained tension flags — anything after that fifteenth chapter’s cliffhanger is going to struggle to live up to what has just preceded it — so that not even the surprising revelation of the reason for Captain Cut-Throat’s actions really hits as it should.

Thus far, then, my experience with Carr’s historical novels remains a curate’s egg. He conjures superb ideas that fold brilliantly into this era which clearly fascinates him so, and at least the plot here largely follows through on its superb opening promise, as not maintained in The Bride of Newgate (1950), but where his strongest tales carry through to alarming and brilliant revelations that changed the face of the genre in which he was working, he time and again seems to run out of puff when he remembers that there’s a plot to be concluded and not just lots of bawdy revelry, swooning women, and men being lantern-jawed and unyielding to fill out his pages. In short, there’s a reason he’s remembered for his revolutionary detection and not his enjoyable historical phase, but this makes the novel overall no less enjoyable.

~

See also:

Ben @ The Green Capsule: Perhaps that’s what’s so hard to explain about Carr’s historical novels – just how fun they are. You have the author’s heavy focus on historical minutia, mixed with an action element that he somehow never made work in his traditional “modern” impossible crime novels … It all comes together in these late career books to create a compelling page-turner incomparable to any of his standard affair.

I have that Penguin edition and yeah, the cover is really very spartan and uninspiring! My Italian paperback (Capitan Tagliagola) was way more exciting … I agree with you about the historical books overall, though I enjoy them enormously (love Fire, Burn) – it is amazing how in books like Burning Court he has his standard 20 chapters but has a major reveal in every single one – incredible.

LikeLike

Fire Burn was one of the very earliest Carrs for me, and I loved it — such a propulsive book, so wonderfully surprising…neither this nor The Bride of Newgate have come close to the excellence of that, though both are superb in their own ways.

I’m glad Carr was able to find something to take a little joy in, especially in the later stages of his career, but, as I say, I have a feeling there’s a reason he’s talked about as a detective fiction author than as a historical writer: his first love remains, I suggest, his better output.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Alan” is probably a nod to Alan Breck Stewart, the Jacobite in Kidnapped (one of Carr’s favourite books).

LikeLike

Still a terrible name for a dashing hero; one is reminded of Tim the Sorcerer in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

LikeLike

Genuine question: In what way is “Alan” an unsuitable name for a romantic hero? (Unaffected by the fact that it’s my middle name.) Does it have associations that I’m unaware of?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I just find the name faintly comical and dull, not helped by decades as an Alan Patrdirge fan. You have these staggering, overwhelmingly impressive feats and brilliant deductions, astonishing bravery, and swaggeringly confident ploys all being pulled off on the page…and it’s just some guy called Alan doing it. Entirely a personal issue, but one I struggled to get out from beneath.

LikeLike

“he time and again seems to run out of puff when he remembers that there’s a plot to be concluded and not just lots of bawdy revelry, swooning women, and men being lantern-jawed and unyielding to fill out his pages” – yeah, that captures the Carr historicals well. A ton of fun, and then Carr finally remembering he needs to wrap up the mystery he introduced, and it always deflates things a bit. They’re still really engaging reads though. This one might be the best.

LikeLike

I’m reminded of the opera house fight in The Bride of Newgate…entertaining, but done for no reason other than Carr wanted to write about a brawl. It’s interesting to reflect that he might have been feeling the restrictions of his earlier successes, eh?

The most out and out successful of the historicals I’ve read is probably The Devil in Velvet, which has very few pretensions towards an actual plot and is content to simply let the research shine through…but even that doesn’t know how to end. So, okay, maybe I think Fire, Burn is better…that at least has a criminous scheme and an ending of sorts.

LikeLike

Not one of my favorites among Carr’s historicals. I see the story of the ship as a disappointment, too much is made of the method of signalling (that particular method may have been overlooked but many other would function in much the same way), the impossible crime has a weak solution and we don’t even get a satisfying come-uppance for the villain. I like Alan and Madeleine, and the depiction of the times.

LikeLike

I have to say, I quite enjoyed that there was no comeuppance for the villain; that meeting between them, when Carr cuts away just as swords are drawn, is completely thrilling, and it’s difficult to imagine any scene topping the face-off itself — so I enjoyed the undercutting of expectation then.

Otherwise, yes, I agree with all your points.

LikeLike

You already know I’m fond of Carr’s enjoyable historical phase and Captain Cut-Throat is a personal favorite, but you nailed their problem in your final line. No matter how good or enjoyable, the historical phase will always stand in the shadow of Carr’s superb detective fiction and locked room mysteries. Not really fair as Carr clearly tried to do something different in addition of having to bring a whole time period (convincingly) to live, which is always going to come at the cost of the plot or characterization. Since all Carr’s historicals are standalone novels taking place in different periods and countries, he had to begin from scratch every time. So, of course, they’ll never measure up to the best Dr. Gideon Fell and H.M. titles.

Maybe he should have published them under a pseudonym. Something inconspicuous like Carter D. Carr. 😀

LikeLike

Since you’ve pointed it out, I’m sure that whenever I read this, I’ll only be able to imagine Alan Hepburn in the image of SNL’s Alan aka Bill Hader…

LikeLike

I don’t know why I find the name so off-putting, but I do. It would be the same if he was called Eric or Donald or Bob…some names simply don’t scream “Hero!” 😄

LikeLike