I’ve heard much about the quality of the 1957 screen version of Witness for the Prosecution, based on the play which was spun from the story of the same name by Agatha Christie. Well, consider this me bowing to peer pressure as I finally check it out to see what all the fuss is about.

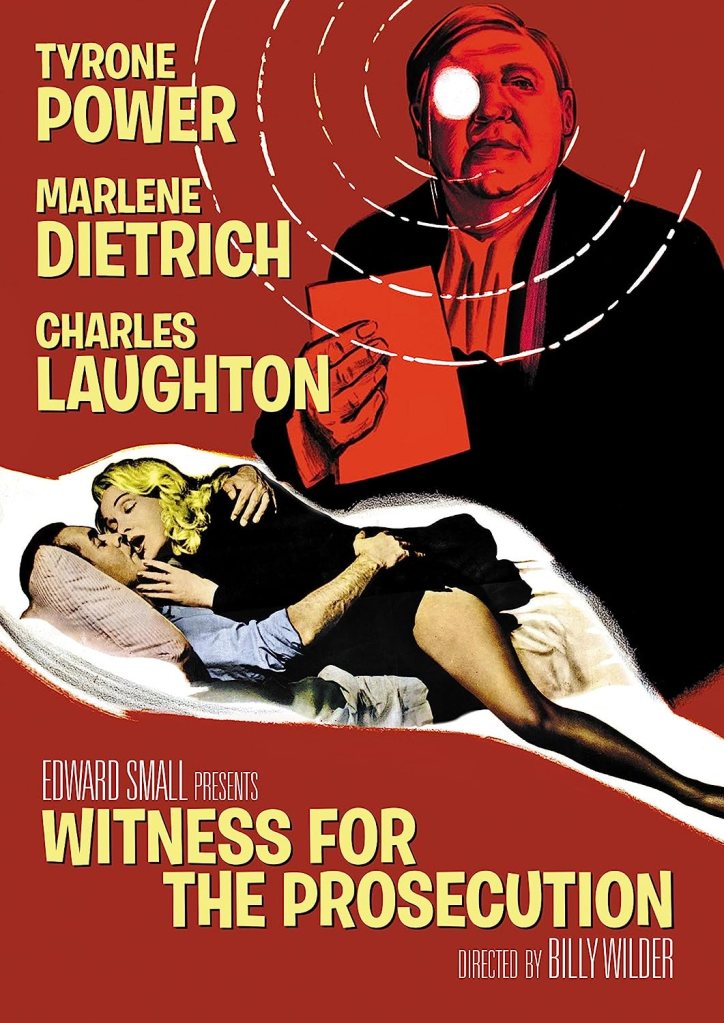

We open with curmudgeonly barrister Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Charles Laughton) returning to work after a heart attack, having apparently come straight from the hospital — not so much discharged as “expelled for conduct unbecoming a cardiac patient”. Laughton, already established as a wonderful cinematic bastard via his superb Captain Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), was born to play this sort of highly-intelligent grouch, one minute verbally abusing his nurse (Elsa Lanchester, bafflingly Oscar-nominated) with dry disdain and the next indulging with almost childlike glee in the use of the stair lift installed in his chambers.

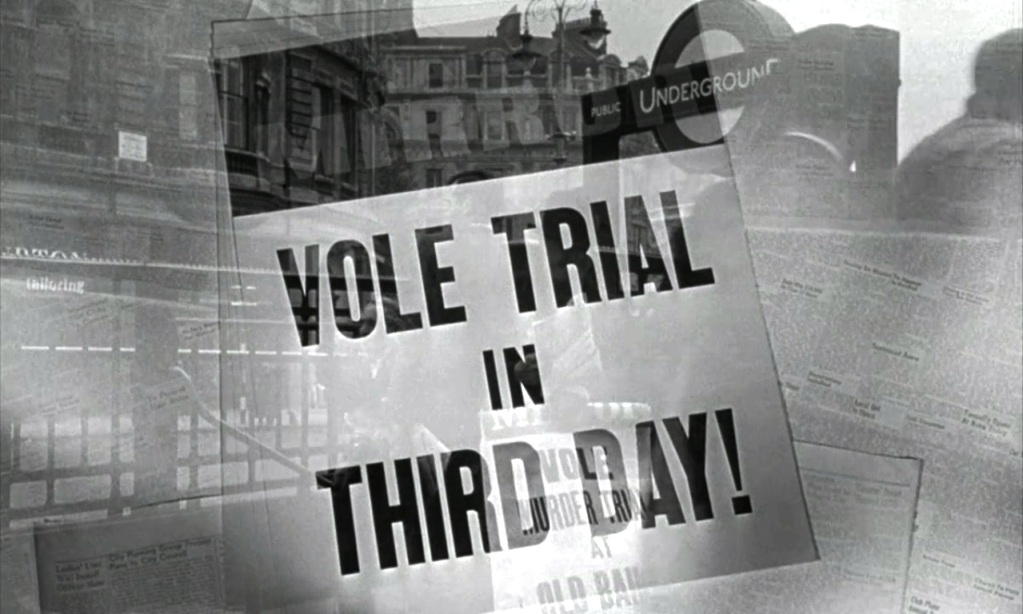

Enter at this point the solicitor Mr. Mayhew (Henry Daniell), with client Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power) in tow accused of murder. Again the characterisation of Robarts comes to the fore — he only agrees to speak to Mayhew because he spies the cigars he has been so cruelly denied by his heart attack in the man’s pocket — and the scene in which Vole and Mayhew bring Robarts up to speed is laced with clever asides and maintains the script’s high level of arch dialogue (“You said I’d like him.”). It sets the scene superbly, not least with the simple shorthand by which Vole makes the acquaintance of Mrs. Emily French (Norma Varden), whom Vole is accused of having battered to death at her home one evening.

The performances in this open quarter set the tone wonderfully. Everything Laughton says comes wrapped in barbed wire, at complete odds with the frankness of everyone else around him — and yet, crucially, for all the comedy on display in the writing we’re not in some kind of screwball universe, with Cary Grant snapping out one-liners too clever for any human being to devise anywhere other than in front of a typewriter. There’s an inevitability to the dry drawling of Robarts, the sense of a man who has seen so much that even when his clear line of defence for Vole is up-ended with a revelation by his junior Mr. Brogan-Moore (John Williams) he simply takes it in his stride. It’s a performance that positively screams of a man in complete control of his milieu, and is perhaps all the more eager to be in control given the recent attack on his health and well-being.

The unflappable Robarts remains unflapped when Vole is arrested, and, after coaching Brogan-Moore on the handling of Mrs. Christine Vole, is unmoved when the equally unflappable lady herself (Marlene Dietrich) appears in time to hear his assessment of her. From the off, Christine Vole is wonderful — sowing doubt as to what she knows and what she has been coached to say, leaning into the post-war prejudices invoked by her German accent…hinting at another side of events which is the first time Robarts shows any discomfiture (“We will accept the evidence of [anyone] as long as they tell the truth.”)

The first mis-step comes, in my estimation, in the extended flashback in which Leonard and Christine meet for the first time. Dietrich’s first scene has already cast several doubts on the warmth and validity of the marriage we know they entered into, and there’s nothing in that wartime encounter which speak of great passion. Were this scene somehow shown first, before we know of Christine’s apparent misgivings, it might work better (it might also work better if Dietrich wasn’t so damn icy, which I’ve found her to be in just about everything from comedy Westerns — where it doesn’t work — to film Noir — where it really, really does). Vole’s faith in Christine is supposed to be misplaced, and Robarts’ cynical view — that he’s relying on his wife “like a drowning man clutching at a razor blade” — the correct one, but this could be achieved just as well, perhaps better, without the flashback to make it all feel so phony.

The courtroom scenes follow what has now become an accepted pattern — first looking bleak for the accused, before Robarts overturns the easy conclusion with evidence that puts an alternative spin on things — with stoic policemen, ‘comedy’ housekeepers, and the usual pompous court officers. Not that it’s boring by any means, the script moving things along quickly and intelligently, and no doubt much of what develops not being the trope at that time that it has become in the 66 years since…which may, in part, be a statement on how successfully things are done here. But only when the eponymous witness is called for the prosecution — played here as a momentary surprise as we sweep ever onwards with the plot — do things feel interesting. Having read the Agatha Christie story that inspired this we are, of course, prepared, but it’s nice to have the bomb drop based on evidence previously provided and then simply carry on without everyone reeling around for twenty minutes.

We revisit here the mistrust of foreigners — especially those of German extraction — in post-war Britain (“…Frau Helm…”), but there’s also a cunning seed here of seeing these proceedings as mere entertainments, as if the deciding over a man’s life were in some way a show being put on (“It’s the first murder trial I’ve ever been to. It’s terrible.”) which is, well, fitting, hein? But any subtlety is then undone with Vole’s testimony being high on melodrama — well, you need to get Academy attention somehow — and Power sweating and gurning in a way that we can be only too grateful was entirely absent from 12 Angry Men (1957).

Any subtlety, too, is lost in the final developments of the mysterious woman who phones with devastating information at the last minute. This works on the page, and it worked in the recent Sarah Phelps-penned adaptation, but here…no. The twist relies on a principle that probably works on the stage but, like Sleuth (1972), the exposing nature of film is too unkind to allow. Even if I didn’t know ahead of time what was happening, I recognise rhotacism, and that alone makes the person involved an interesting choice to hinge this particular reversal on. You applaud the boldness of Billy Wilder in putting this so brazenly on the screen, but it tips the whole thing into farce for me, playing straight something that is patently ridiculous. Maybe you loved it, but I couldn’t stop smiling at how cod serious it all felt.

The script by Wilder and Harry Kurnitz has an additional surprise — possibly this is in the stage play, I haven’t seen it — which kind of works, but for all the joy of seeing everything laid out in the final stretch the film never quite recovered the gravitas it had prior to the above development. Robarts’ sudden volte-face in the very final moments really doesn’t ring true for me, either, and feels more like a movie ending than anything which comes naturally from the preceding two hours spent with this man who we feel we’ve come to know so well (and quite why so much runtime was devoted to him taking pills and having injections is beyond me — the opening scenes already established his desire to be back at work despite the risk to his health, and these interruptions go nowhere).

Overall this is an enjoyable adaptation which adds perhaps a little too much in padding 15 pages out into 116 minutes, especially as so much of Wilder’s direction feels so static (compare the roving, hungry camera of 12 Angry Men to the fixed shots here). I did struggle to keep a straight face through the final quarter, but — as much as I enjoyed the cynical coda Phelps added to her version — I liked the simplicity of the motive behind all the shenanigans, and Laughton is always wonderful to watch. I’m not quite convinced that this is the classic I was sold, but I do appreciate old school movie-making in this era when so little seems to be willing to let you sit and absorb an experience (god, I sound old). I’m glad I watched it, but it won’t linger in the mind as 12AM did. Indeed, but for a few oddnesses (what the hell is “the monocle test”? — you shine a light in someone’s face and see if they put up with it?) and Laughton’s wonderful central turn, three years from now I might not even be sure I’ve seen it.

Well, of course I adore this film, which is not to say that I disagree with some of the problematic aspects you bring up. I do think that Laughton is the crux of the film’s success, and his interactions with the various “straight men” around him delight me no end. The casting of Power and Dietrich pose issues: he’s too old to play Leonard, and she’s so distinctive that the final phase of plot is . . . well, problematic. I think the flashback was largely an homage to Dietrich, who had made such a splash years and years before in THE BLUE ANGEL: it gives her the chance to be glamorous and to sing. I totally understand why it strikes you the way it does, but I am fine with it.

In Christie’s play, she extended the ending to provide justice against the murder. I don’t know if you got to see the London production that took place a few years ago (it was wonderful), but Christie’s play ends with a strike of a knife. Since the movie really focuses on Sir Wilfred, I love how Wilder extends that twist to give him a full recovery at the end. Anyway, I’m glad you watch this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That stage production, last I checked, was still running in London Brad. When you are next here we’ll take Jim with us (handcuffs optional 😁)

LikeLike

I’d love to see the stage version; a comparison of all three takes on the story would be fascinating.

LikeLike

We could arrange an outing …

LikeLike

We could…

LikeLike

👍

LikeLike

The characterisation of Robarts is exceptional; his confidence in the opening stages as a smokescreen against his recent illness, the way he’s almost gobsmacked when Christine implies that what she’s going to say in the dock might not be the truth…it’s a glorious piece of character work on the page, brought to wonderful life by Laughton.

And that’s also part of the problem, because I simply don’t believe that the man who is so disgusted at the actions of the Voles would be so keen to leap in two-footed to defend a woman he saw commit a murder in front of him — he has too much respect for the law for that. It makes a lovely Hollywood ending, but the Christie ending sounds (unsurprisingly) much more true to the narrative.

I’ll have to check out the show at some point; with the AC name attached to it, I can’t believe it’s going anywhere any time soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By that same argument, how could one believe that Hercule Poirot would offer a false alternative solution to the murder on the Orient Express – and then let the killer get away with brutally stabbing a man to death? It’s “Golden Age Justice.” I’m sure people are divided on whether they can buy it of Sir Wilfred or not. My own opinion is that his own unorthodox legal methods make him open to a different view of justice. He sees that act as an execution rather than a murder, and he acts accordingly. And I suspect that Leonard’s blithe disregard for Christine’s sacrifice at the end puts the audience on her side and makes them applaud Sir Wilfred’s choice.

On the other hand, the play’s ending is more blood-curdlingly dramatic and works much better for the stage! Go see it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, the Poirot example doesn’t hold because that was the evening up of a hideous crime — but let’s not get into that, or we’ll be here for months. Let’s agree that anyone can act unpredictably in any given situation, and that fictional characters should be no different in this regard.

LikeLike

Yeah, I think both Roberts and (especially) Poirot are primarily concerned with what they consider justice, and both (though again, especially Poirot) hold that justice does not always align with the rule of law. On his deathbed Poirot wrote “ by taking Nortons life, I have saved other lives – – innocent lives. But still, I do not know… It is perhaps, right that I should not know. I have always been so sure – – too sure…” which clearly points out that his past extra-legal decisions were unaccompanied by uncertainty, and puts any claims of “moral anguish that she just didn’t around to mentioning” in MOTOE to rest. But it’s not just MOTOE… he basically followed the law whenever it just happened to align with what he considered justice… and which really wasn’t all that terribly often! And if I were to name Christie’s most famous novels (correct me if I’m wrong here): And Then There Were None, Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd— not one of them concludes with the culprit being delivered to legal punishment.

With Robarts, presumably there is a greater belief in— and devotion to— the law. But I really don’t think we’re talking about anything approaching a Javert here. I don’t think Robarts would attempt to prove that Christine Vole was not guilty of murder, but he would presumably do everything to suggest that it was justifiable homicide.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am of course in complete accord with Brad – the flashback is a way to open up the play and let her sing a song (even Hitchcock had to make that concession to get her in STAGE FRIGHT). And Power does look a bit old (he was 43 at the time it came out) but then he was extremely unwell and died very shortly after. His over-emoting on the stand is of course there to support the twist. (When I first saw the film aged 13 in 1982, I completely fell for the disguise by the way).

I was deeply troubled by the truly absurd notion that you enjoyed even a second of the Phelps version, which to me is an utter piece of claptrap, mired like all her Christie works in a miserablist and grotesque world view that speaks for her work as a writer on Eastenders (and the fact that she doesn’t know Christie’s work at all – she has only read the books she has, ahem, “adapted”). Not sure why you commented on what Wilder had to do to spin out the short story though – the unbelievable and unbelievably bad Phelps version was based on the short story only as they didn’t have the rights to the play; Wilder was adapting the play not the short story. Sorry it didn’t do more for you Jim – I’m a huge fan and it’s one of only a handful of movies that are faithful to Christie and manage to convey their charms and strength in a cinematic way. Come round to my place and I’m sure in a few hours I can turn you around (will make lots of great pasta too).

LikeLike

Sorry, you’re right about the comment I made about spinning out the story — my fault, I’m in ignorance of the play and forgot about that aspect when I reached the end of the review (it’s mentioned in the first paragraph though; go back and check!).

As to the Phelps version…hey, I like the make-up and the cynical era-appropriate sting she put on things, and don’t consider her twist on the material to be as abortive as, say, The ABC Murders (I didn’t watch her Ordeal by Innocence…but it sounds like it treated the material about as respectfully as a late-era Suchet Poirot adaptation). The miserable home life, grimy sex scenes, and gloomy, foggy setting of the whole thing I could do without, but that make-up job was superb: it had me questioning whether she was even using the same twist as in the short story.

Next up, maybe I’ll watch the 1974 Murder on the Orient Express…after all, I’m a Lumet fan now 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

12 Angry Men is a sensational bit of drama. I quite like his ORIENT but it is too long and gloomy for me, though it looks and sounds great and the star magnetism is a bit of a wonder. His THE DEADLY AFFAIR, from le Carré’s first Smiley book, is pretty interesting btw. Much prefer the livelier Ustinov NILE, though remain a huge fan of the Branagh versions). What’s maddening about the Phelps Witness is how un-Christie-like it is, how fundamentally unsympathetic to its intentions (even if the short story lets the villains get away with it, most of the rest is her demented and depressing invention after all. But sure, prosthetics have come a long way since the ’50s 😁). And this is from someone who takes a pretty broad view when it comes to adaptation after all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also The Verdict, right? I seem to remember that getting a thumb or two up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

THE VERDICT is a fantastic drama – one of Lumet’s best. But not a thriller, unlike his other courtroom film GUILTY AS SIN, which is trashier but great entertainment. DEATHTRAP, from Ira Levin, is also great fun. RUNNING ON EMPTY, about a family on the run from the FBI, is really worth seeking outm

LikeLike

Running on Empty starred River Phoenix, didn’t it? I remember watching it when I was a wee lad, but can remember nothing about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s the one – I have always been really impressed by its combination of elements (music, FBI, teen romance, family drama) and unusual point of view (what happens to 60s radicals decades later).

LikeLike

The Verdict is brilliant – but I get in trouble waving that word in your face!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, one of these days we may find out about that…

LikeLike

Jim, I entirely agree about the flashbacks. It always annoys me when flashbacks— which are arguably the most effective cinematic device in conveying the retrospective power of puzzle plots— are used in them instead for exposition which has little to no payoff, and could easily and more concisely accomplished with a few brief lines of dialogue. I understand the commercial reasons for them here, but I do t find them defensible artistically.

And I also quite agree about the star’s rhotacism making the casting odd and, I would say, a misjudgment (and a further misjudgment, I believe, was to introduce the second character— if only for the few first seconds— by voice alone, free from physical deceptions and distractions that might have diffused our concentration on that vocal peculiarity). That said, many people I know— indeed, most people I know who have seen the film— have been fooled by it… fooled apparently due both to the apparent adversarial intent of the new character, and the fact that for many, rhotacism is easily accepted as an adjunct of a Cockney dialect (it’s perhaps not quite the same thing, but most Cockney voices have fairly weak “r” sounds, especially to Amurrican earrs). That is, to their minds, “both” characters have different reason for not pronouncing their r’s.

Moreover, if there’s one impossibility I do believe in, it’s the impossibility of the knowing mind to overcome the “curse of knowledge.” That is, short of amnesia, it is simply not possible for any of us to put ourselves in a place of ignorance regarding that we already know. I too find it difficult to believe I would’ve been fooled by the WFTP disguise aspect had I not already known about it. But it’s amazing how the knowledgeable mind zeros in on aspects the ignorant mind is not looking for or otherwise justifies due to other preconceived notions. We just don’t know. I credit you with particular savviness and a superior level of puzzle plot discernment, but I simply do not believe any of us can know after the fact what our unprepared minds would have told us. I’m not suggesting you wouldn’t have known, I’m merely suggesting that you can’t know if you would have. And hell, I can believe that The Mirror Crack’d genesis was pure coincidence!

The “curse of knowledge” is a very fascinating psychological phenomenon. I’ve had many people tell me they were extremely surprised by the “twist” in my one-act comedy— a “twist” that I would presume no four year old child would be fooled by. But we often don’t see what we’re not looking for, and the fact that it’s billed as a one-act comedy ( even if a one-act comedy about Agatha Christie, for God’s sake!) is enough to keep them looking for plot reversals! I know that a practically undisguised twist in a 1932 jewel robbery comedy blew me away, while the solutions to Ackroyd, Orient Express, A Murder is Announced and even The Burning Court were transparent to me. I too wish Wilder’s film were more deceptive, and less fragile in that respect, but I’m convinced its reputation as a classic is not nearly solely attributable to the amusing Laughter/Lanchester “Man Who Came to Dinner” byplay. No, it is also beloved because its revelations actually blow most people away.

An interesting point a friend brought up is that the threat of perjury to Christine Vole is non-existent. I haven’t reviewed it carefully, but I believe my that friend is right: everything Christine said on the stand was true— she simply arranged for it not to be believed.

LikeLike

That was a Cockney accent she was doing? Good heavens.

As I’ve said above (or below…), the make-up in the Sarah Phelps-penned version was so good that it had me suspecting an entirely new twist, like maybe they were going to use it as a double bluff or something. Here, the makeup is superb, but that distinctive voice is, for this Englishman, too distinctive. The equivalent from my youth would be like putting peak-era Arnold Schwarzenegger in a wig and fake moustache and expecting me not to notice it was the same person. We’ll never know, of course, but I’ll maintain that another actress would have convinced me that others wouldn’t see through so easily.

Fascinating principle about the perjury, and I’m almost tempted to watch the second half again with that in mind. Now that would make a surprise ending that Erle Stanley Gardner would be proud of.

LikeLike

I entirely agree that “another actress would have convinced me that others wouldn’t see through so easily.” I think it was a tremendous mistake to cast Dietrich for this reason, and adding insult to deceptive injury to have the first few seconds of the “Cockney” woman (yes, its supposed to be Cockney— and Noel Coward helped her with it!) consist of voice only. The irony is that Billy Wilder, who learned a great deal about surprise, expectations, and plot symmetry from his mentor Ernst Lubitsch (whom I suspect would have been the greatest of whodunit film directors had he so chosen) seems to have exhibited a greater puzzle plot sensibility in his non-whodunit films plots than in his one true puzzle plot. His WITNESS I find a triumph as a character comedy, but a disappointment as a mystery, considering both Qilder’s skill and the great promise of the source material.

I was merely asserting the belief that we can never know what would or wouldn’t have fooled us. The “curse of knowledge” is just that. The mind has a remarkable capacity of acceptance or dismissal based on our expectations. The magician’s most common method of making a small handkerchief disappear is a classic example: few people unfamiliar with the method catch on to it, but those who know have trouble believing that it could fool anyone. And thus it often takes magicians awhile to trust that it can be effective. In my experience, the only people who have ever seen thru it are those who have been shown or given the gimmick in magic sets (of which it is unfortunately far too frequently an included item).

This even applies to the disguise in the film version of SLEUTH which (I think even more remarkably) has fooled quite a few people (I consider Dietrich’s disguise quite deceptive in comparison). When asked about it, many of those taken in do recall a passing thought that this new character resembled Caine (just as they say retrospectively of the Cockney woman, “yeah, I was thinking she sounded a bit like Dietrich). Still, they readily dismiss the idea that it could actually be Caine because, after all, his character is already dead— and they have no expectation of deception from that quarter because, as far as they’re concerned, they’ve been watching an inverted mystery story…

LikeLike

I am glad we are In complete agreement, Sergio — and a bit concerned that you seem to handle WordPress technology like my mother . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤣 Jim has very kindly fixed my touchpad maladroitness (thanks mate). I really, really tend to fail with the app on my phone. Mind you, there were so many typos on my old blog, no wonder it gave me up …

LikeLike

I very much fall into the Brad and Sergio camp on this film. I think it is an excellent, suspenseful thriller and Wilder and the other screenwriters do an excellent job of opening up the play and broadening the characters. Laughton is, of course, excellent and the way he growls through this movie has been imprinted on my brain since I first saw it at a pretty young age. The supporting cast are uniformly great too even if – I concede – some of the theatrics of Dietrich and Power verge on the melodramatic. (I distinctly remember watching clips of this film during the one and only meeting I attended of the high school mock trial team and Christine’s “Damn you! Damn you!” generating nothing from laughs from that crowd.)

I have not seen the Sarah Phelps adaptation, but your point about the costuming is one that applies to such much of Christie. There are a handful of adaptations handle it well, but I am sure that that particular plot point is one that causes much ire at the development stage of any Christie project.

I hope that you consider watching the Lumet MOTOE. It is my favorite Christie adaptation of them all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The only bit that seemed over-serious to me was them not recognising Dietrich as soon as she opened her mouth in that disguise — I honestly burst out laughing, and failed to take too much from that point seriously until that admittedly great little addition to the end.

Common consensus has the Phelps adaptation as among the worst crimes committed by humanity, and while I don’t think it’s that bad it certain delves more into the sex lives of our barrister than I feel is necessary 🙂 It’s an odd brew, but the speech at the end is in my opinion excellent, and sort of justifies the cynical tone throughout if you take that as the raison d’etre of the whole enterprise.

Incidentally, The Improbable Casebook of Sherlock Holmes creeps ever-closer to the top of my TBR. Expect a review in the coming weeks — really looking forward to it.

LikeLike

I enjoyed a lot the book and the movie

LikeLike

I enjoyed them both, I’d certainly hate to give the impression that I didn’t enjoy the film. I’m perhaps hamstrung in my admiration by first experiencing it now as an old, bitter, and jaded man, but it’s good…just not quite the timeless classic others have claimed.

LikeLiked by 1 person