It would be difficult to overstate the respect I have for the work done by Robert Arthur in the mystery genre. From creating The Three Investigators to turning out highly enjoyable fair-play mysteries for younger (and older) readers, the man displayed a brilliant creativity and a talent for diversity that makes every encounter with him a joy.

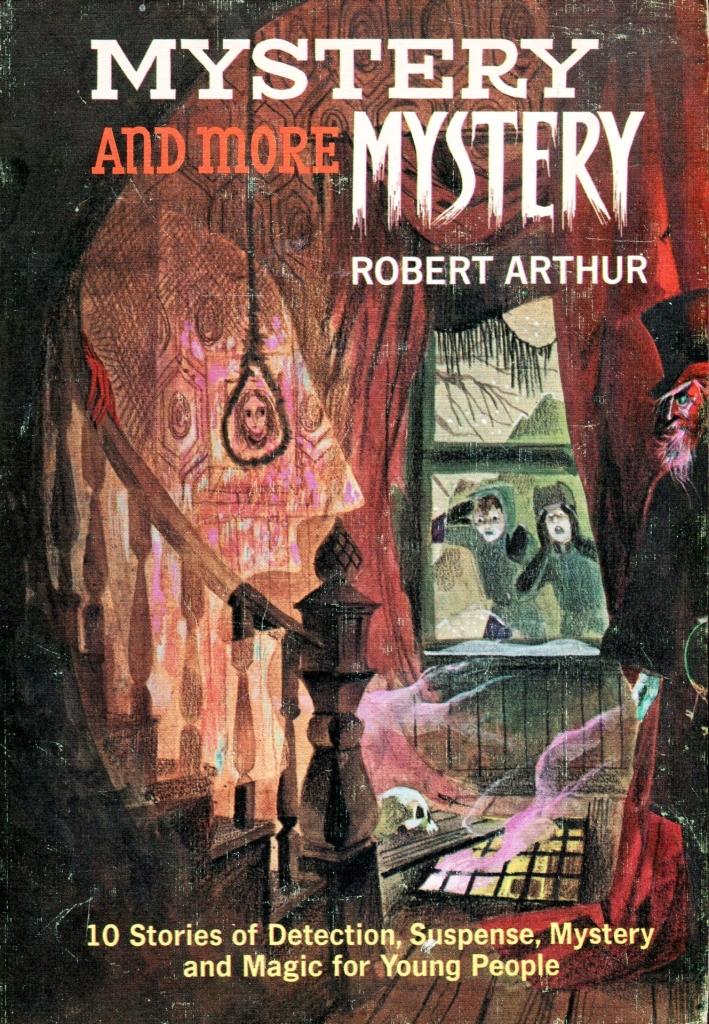

Until I have the money, patience, and contacts to track down his remaining stories — or until someone has the brilliant idea of collecting them together in what must be one of the most essential anthologies not yet assembled — the collection Mystery and More Mystery (1966) is the last of Arthur’s work I’ll encounter for a while, and so I intend to draw out the ten stories herein for the five Tuesdays of June. It’ll look like this over the coming weeks:

Week 1: ‘Mr. Manning’s Money Tree’ (1958) and ‘Larceny and Old Lace’ (1960)

Week 2: ‘The Midnight Visitor’ (1939) and ‘The Blow from Heaven’, a.k.a. ‘The Devil Knife’ (1936)

Week 3: ‘The Glass Bridge’ (1957) and ‘Change of Address’ (1951)

Week 4: ‘The Vanishing Passenger’ (1952) and ‘Hard Case’ (1940)

Week 5: ‘The Adventure of the Single Footprint’ (1948) and ‘The Mystery of the Three Blind Mice’ (1963)

Yes, I’ve read some of these before. I don’t care, I’m going to read them again — Arthur is always a delight, and time in his company will not be passed up.

‘Mr. Manning’s Money Tree’ (1958) was originally published in Cosmopolitan, and credited to Arthur and his wife Joan Vaczek (under her nom de plume Joan Vatsek). Following the “sandy-haired, amiable young man”as he leaves the bank where he works as a cashier for lunch, we’re swiftly made aware that all it not what it seems: a man is tailing him, meaning that Manning will have “no chance to hide the ten thousand dollars which at the moment was safely tucked away inside his innocent-looking thermos bottle”. Henry Manning, it seems, has been skimming off the top at the bank, and has purloined some $30,000 to fund the “market fever” that has gripped him…and it seems he’s been found out.

He had no intention of trying to run for it. He’d take his punishment. Who wanted to spend the rest of his life a hunted man? But he did want to be able to count on the money in his brief case to help him make a new start.

Cue some quick thinking, and Henry loses his tail, hides the misappopriated funds, and returns to the bank to be arrested and serve three-and-a-half years in jail.

At this point, I was half expecting the story to take a turn not unlike ‘The Shadow Points’ (1933) by MacKinlay Kantor, in which a criminal similarly hides his loot in an ingenious place and returns after several years to claim it. But Arthur does something more, turning the story to focus on Henry’s involvement with, and growing affection for, a married woman which, for reasons best left discovered, get complicated by the money he wishes to claim. I’m not entirely sure that anyone would actually exhibit the sort of patience Henry does, but the genius of this tale is how the emotional in-roads build in the foreground while the nettling awareness of the money in the back of everything threatens to poison the progress Henry makes.

The increasingly elegiac tone that pervades proceedings is rather magnificent, it has to be said, as the money subtly changes from a fixation to an inconvenience to a potential nest-egg to, finally, something from which a sort of release is achieved on account of how the narrative unfolds. I don’t think the final line is as necessary as plot mechanics demand — the idea of scores being settled is surely a bit too oafish for so delightfully touching a piece of fiction — but it also doesn’t ruin anything that has come before.

There’s another parallel with the work of MacKinlay Kantor in that, much as in the collection It’s About Crime (1960), the focus of Mystery and More Mystery seems to be a jumping of tones and approaches from story to story. How else to justify the choice of ‘Larceny and Old Lace’ (1960) as the second tale herein? Septuagenarian sisters and classic mystery fiction aficionados Florence and Grace Usher (“Why, my goodness, we each have read more than a thousand mystery novels, haven’t we? We know about London from Agatha Christie and Margery Allingham, about Miami from Brett Halliday, about Chicago from Craig Rice…”) are delighted to have inhereted their ne’er-do-well nephew’s house in a run-down section of Milwaukee and, after taking a train into the city, eventually make their way to the offices of lawyer Mr. Bingham to learn about their windfall.

“How did he die?” Florence asked, pressing her gloved hands together in eager interest.

“Well,” Mr. Bingham rubbed his high forehead distractedly, “he died of a form of heart failure—”

“I suppose,” Grace agreed, “that you could call three bullets in the heart a form of heart failure. However—”

“Two bullets in the heart,” Florence corrected. “The coroner’s report said the other missed by several inches.”

One is reminded throughout of the delightful Lutie from Our First Murder (1940) by Torrey Chanslor, especially when it turns out that someone else wishes to get their hands on the house for — duhn-duhn-duuuuuuuhn — nefarious purposes, and the sisters find themselves confronting a thief and, eventually, the criminal mastermind who has the town “sewn up” and is keen to kill them to get what he wants. If it doesn’t quite have the brilliantly contrasting gallows humour of the Jopseph Kesselring play (well, more the Frank Capra movie…as I’ve not seen or read the play) from which it takes its name, it certainly earns the comparison.

It would take a very hard heart indeed not to get swept up in the delight the sisters feel at being able to solve a mystery of their own (“What joy, Florence, what a triumph! Even Nero Wolfe would be proud of us.”), and if the Poe allusions that tickle along throughout don’t quite pay off as neatly as they might…well, there’s easily more than enough glee in the writing (the sisters sitting “subdued but defiant, like two ruffled hens” is sublime, as is the schoolmarm-ish way they berate poor Tiny Tinker for using a double negative during their interrogation of him) to carry you along with nothing close to a complaint. Surprising, too, given that this is a collection for younger readers, how little sympathy is evinced for the departed nephew (“Walter was always a rapscallion. I certainly did not intend to lose my life over him.”) — there’s a casual emotional maturity there that older eyes might simply pass over, and Arthur deserves credit for confronting it so easily.

At the back of this collection there is a chapter in which Arthur addresses the old “Where Do You Get Your Ideas?” chestnut, which tells us nothing you wouldn’t expect for these two stories: the first concerning how a man could hide money easily in the city so that he’d be able to find it again, the second “because the contrast of two little old ladies pitted against tough criminals and winning out seemed funny”. I suppose he’s not really going to get into the idea of morals, ethics, obligation, and conformity in a light bit of ‘behind the curtain’ writing for his intended audience, but I’d be fascinated to know more about the decisions made in ‘Mr. Manning’s Money Tree’ in particular. Alas, not to be.

Well, we’re off to a great start, just as I’d hoped. See you next week for more.

To what degree do you view these stories as being for “young people”? I read both of the reviews above and found myself sanity checking whether I was mixing up “minor felonies” and “little fictions” again, because neither sound particularly juvenile. For that matter, I read The Glass Bridge by Arthur a while back, and it seemed like you could plop it into any impossible crime collection without anyone batting an eye. Is Arthur “unfairly” labeled as a young adult author, and being consequently overlooked?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, excellent question.

I suppose there’s nothing inherently junior about these, but they’d fit just as easily into a juvenile category as they would anything intended for, er, non-children. Maybe that’s what Minor Felonies should become in time — something that doesn’t necessarily have to be written for a younger audience (‘The Glass Bridge’ is in this collection, btw) yet cold be put into such a collection, or bought for younger readers, without anything about the contents, theme, or workings requiring an understanding above that of the average, say, 12 year old. Oh, man, I am going to seriously over-think this now.

As to Arthur being overlooked because of his categorisation as a children’s author…I think the bigger problem is that he’s totally out of print. Apart from the Mike Ashley collection about 20 years ago, I’m unaware of any single one of his novels or short stories being readily available for someone to buy in a bookshop and read. You can’t overlook someone until they’re there to be looked at, right?

LikeLike

Perhaps he’s being overlooked for republication due to the junior label. I’m not sure what the young adult market is for material from sixty years ago… which is too bad, as it opens a window that I think young minds are ripe for.

LikeLike

Yeah, and a handful of enthusiastic comments here aren’t going to change that, eh?

I imagine that there’s so much pressure on authors these days to fight for space in an increasingly crowded market, having to compete against someone who’s been dead for a few decades is even less appealing. So when collections of short stories are assembled, they’re more likely to be drawn from living authors who have a career of their own to promote. Which makes perfect sense — authors gotta eat, just like the rest of us — even if it is a shame that it means great stuff like this gets squeezed out and gradually forgotten.

LikeLike