Approximately two months ago, Kate at CrossExaminingCrime invited a bunch of bloggers to contribute to a collaborative post on our favourite mystery movies. You can view the results here — without my contribution, because, despite being given plenty of warning, I couldn’t organise myself in time.

I had earmarked the Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant vehicle Charade (1963) and, having finally gotten round to rewatching it, thought I’d write about it here instead because it’s such a joyous time and I had a blast revisiting it after a number of years.

After a lightning-fast prologue sees a dead body thrown from a train, we start with Regina ‘Reggie’ Lampert (Hepburn) on holiday and contemplating divorcing her husband Charles. In this frame of mind, she meets the charming Peter Joshua (Grant), they trade some banter, and part ways. Returning to Paris, Reggie discovers the apartment she and Charles lived in stripped bare, fast upon which we learn that Charles was the dead man thrown from the train at the start, having sold the entire amassed possessions of their lives and apparently fleeing the country.

A rare moment of repose for Reggie (Audrey Hepburn)

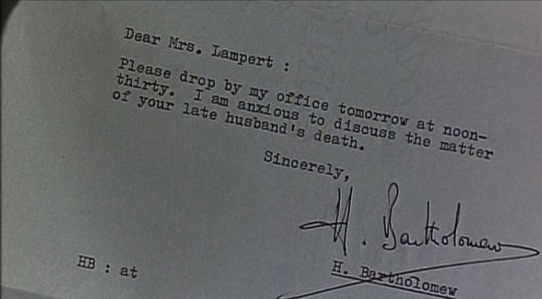

From here, re-enter Joshua, who has seen the news of Charles’ death in the papers, and add four men who will drive the rest of what is about to unfold: FBI man Hamilton Bartholomew (Walter Matthau) and the trio of crooks he’s hunting Tex Panthollow (James Coburn), Herman Scobie (George Kennedy), and Leopold Gideon (Ned Glass). It would appear that these three and Charles stole something very valuable several years ago, and that Charles sold it, kept the money, and was doing a runner when one of the three caught up with him and killed him trying to claim what they felt was theirs. The only problem is, whoever killed Charles didn’t find the money, and since he’d sold everything else it must have been either on his person or secreted somewhere…but no-one knows where.

Herbert Bartholomew requests an audience

There’s so much going on here, I don’t even know where to begin. Ostensibly the setup for a sort of international thriller, at the insistence of Inspector Grandpierre (Jacques Marin) all concerned must remain in Paris, and so as suspicion centres around Reggie, and Joshua offers his assistance — and as the three increasingly-impatient thieves try by various gambits to intimidate Reggie into handing over a fortune she doesn’t possess — the script becomes something altogether more elusive. There’s certainly an aspect of detection in the location of the $250,000, and, as the relationships between characters get ever-more murky and complex, classic detection staples like identity begin to raise their head, and then the whole thing becomes a murder mystery as the splitting of the money takes on a sort of tontine aspect; and of course there must also be romance, smooth though the path of that ne’er did run.

Whoever cleans this carpet should be fired…

And yet the movie never once feels overstuffed, or unable to give each element the attention it deserves. Peter Stone’s script whisks these ingredients together beautifully, toying with the trappings of the thriller, the detective story, even to a certain extent puzzle plotting as a variety of deaths occur to men all wearing pyjamas (the man found drowned in his bed is an especially genius touch in how to take the apparently miraculous and make it mundane) and we get a dying message clue that is as simple as it is easily-misunderstood. And the cast are clearly having a great time knowing that everyone gets a chance to make their mark. Coburn in particular, ludicrous Texan drawl and all, clearly belongs in a role that for all I know was custom-tailored to his needs; the tracking shot that introduces him to proceedings, when he appears at Charles’ funeral and struts effortlessly down the aisle of the church, captures his loose-limbed insouciance gorgeously, and the menace he brings to his interactions with Hepburn is remarkable when you consider how goddamned charming the man was in so much of his work.

Tex (James Coburn) would like a word, too…

What especially makes this stand out for me, aside from the expected ingredients of Grant’s charm and Hepburn’s doe-eyed appeal, is how intelligently it’s filmed. As a director, Stanley Donen is clearly happy to let his performers and script take a starring role, and to deploy Henry Mancini’s music to sparing but striking effect. The film-making here feels weirdly incongruous in how happy it is to not show off: witness the real-time, unbroken shot of Joshua and Scobie ascending a building in a lift (elevator, if you will), in which Kennedy and Grant simply occupy separate sides of the screen and…just watch each other while the floor numbers tick by. What little action there is — and it makes no pretense to be an action movie, being more than happy to thrill your grey cells — has, of course, dated and looks horribly staid by today’s smash-a-car-through-everything excess; however, the scene of two men fighting on the roof of a building, thoroughly unchoreographed and without a spin kick or a thigh-scissoring in sight, with no quick cuts and almost no music to soundtrack it really makes you feel it.

Scobie (George Kennedy) and Joshua (Cary Grant) ain’t sayin’ nothin’

And the framing of certain shots, like that fight, is fascinating, too, since the cameras couldn’t move quite so freely back then and so you sometimes just get a wide shot of something interesting happening without the need to cut all over the place for coverage. There’s something of a Citizen Kane (1942) homage, too, in Joshua’s first reappearance in Reggie’s life following the revelations about Charles, with Donen happy to cast his no-doubt expensive leading man entirely in shadow, so that Grant is a silhouette to us (and Reggie) when they have their first serious conversation. Sure, sure, you can claim it’s an allegory or something, go for your life, but whatever it is it’s damn rare enough to find, and to find it done with such confidence is heartening indeed. In a genre that Alfred Hitchcock had more or less claimed for his own at this point in time, and where the most tempting route was surely mimesis, Stone and Donen have combined with one of Hitchcock’s most successful leading men to produce something which should never be slapped with a lazy “Best Film Hitchcock Never Made” sobriquet.

It’s cheaper than hair dye, I suppose…

And, best of all, the various mysteries are actually surprising; quite a few reversals throughout are handled brilliantly, with the revelation of who’s responsible for the murders actually eliciting a gasp from the friend I watched this with even though I’d argue that’s far from the biggest surprise in here (though surprising it no doubt is, not least because there aren’t really any clues to lead you to that conclusion with anything beyond guess work…). The biggest mystery, resolve in the final scene, was the point where I knew I loved this film when I first watched it: for something so light and fast and witty and clever to stick the landing so perfectly was a the crowning glory on a marvellously confident display from all concerned. It’s fast, it’s funny, it’s dark, it’s wickedly clever, and it contains a few twists and surprises that I guarantee will catch you out even 56 years later. Check it out if you don’t know it; I guarantee you’ll find something to love.

Grant’s such a pro, he even makes the ‘comedy orange’ routine work

Great movie JJ and really enjoyed your review. I am not sure how much Marc Behm contributed to the script but Stone was a very clever and witty writer.

LikeLike

I came to this after seeing The Taking of Pelham 123 (1974), having been drawn in by Matthau’s performance in that later film — prior to that, he had always been a comedic actor to me — and eager to see more of his “straight” work. Without realising Stone had written both, I remember thinking that the tonal shifts and the balancing of hard-edged moments and then the steady steam-pressure release had about it elements of Pelham.

Can’t remember how long it took me to discover they were written by the same person, but now I feel like the fingerprints on both scripts are so durned obvious that I should have seen it immediately.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, big fan of PELHAM. Doesn’t help that Stone occasionally had himself credited as “Pierre Marton”. He gets a credit on the CHARADE remake as “Peter Joshua” which is even funnier. I wrote a review of PELHAM a long time ago: https://bloodymurder.wordpress.com/2012/06/19/the-taking-of-pelham-one-two-three-1974/

LikeLike

Ha, amusing since “marton” en Anglais is, I believe “stone”.

Reminds me of Robert Crais opting to be credited on some of his TV writing as “Jerry Gret Samouche” — and approximate English phonetic rendering of “I’m sorry, this is rubbish” in French 😀

LikeLike

I agree with all you say here, with an extra dollop of love for Mancini’s score! As someone who knows his Hitchcock, I see the surface similarities but find Charade distinctly lacking in Hitch’s neurotic preoccupations. It’s a beautiful romp, and I hope Donen cherished the fact that he got to work with the stunning Miss Hepburn, and Hitchcock never did. (He planned to, but it never worked out!) Cary Grant is especially cold here because the plot demands he be that way. Hepburn makes this movie as warm as it is. She was a treasure, one of my favorite actresses even if I didn’t always love the movies she was in. (But I love this one!)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Moreso than Grant for me, Hepburn really captures that idea of “star quality” — in part, I’m sorry to say, because I’m not convinced she’s all that great an actress and yet I cannot take my eyes off her when she’s on screen. I include that shot of Grant juggling with the orange at the end of the review partly because of how compelling I find Hepburn in the slim slice of screen she’s given while he gurns and twists (to, frankly, wonderful effect — I’m not knocking the gurning and twisting, and his facial expressions are sublime).

It’s interesting that the closest Hitch ever got to this sort of carefree thriller was with Grant in North by Northwest (1959) a mere four years earlier. As you rightly say, there was far too much neuroses elsewhere in what Hitch did (once he got to Hollywood, anyway — his early British stuff is joy unconfined) for him to pull off the sort of light comedy needed here. Telling, too, that Hitch’s only outright comedy — The Trouble with Harry (1955) — is a weird kind of comedy that I’m nt entirely sure was ever actually all that funny. And, I suspect, at least partly the inspiration for the title of the terrible, terrible remake of this in the early 2000s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A superb film well evoked here. It’s one of those that gets better with revisits – the first viewing can be a tad confusing with all the twistiness of thee plot, or at least I seem to remember that being the case for me when I first saw it as an adolescent.

All the performances are great, the grotesque black comedy sitting very comfortably with the thrills and pretty much every cast member hitting exactly the right tone. Essentially, everything works, and that Mancini score is top drawer stuff.

LikeLike

I hadn’t watched it for a few years, and the freshness of it still was a lovely experience. There’s so much good stuff going on plot-wise that, even when you know it inside out, I reckon there’s still plenty of joy to be had in simply watching how it all fits together.

The closest thing I’ve found to this much enjoyable, infectious lightness and intelligence in modern cinema is The Brothers Bloom (2009) from Rian Johnson. That has an equal balancing of thrills and laughs, switching with the same suddenness and ease, and with a similar smartness that will wrongfoot the overwhelming majority of its audience. If you’ve not seen it, I recommend it.

LikeLike

Yes, I completely forgot about that one. I saw it in the cinema when it first came out and I remember really enjoying it. Nobody else I know seems to have seen it though!

LikeLike

Well, Johnson’s a big — and sometimes unpopular — deal now post-Star Wars, so maybe it’ll get a second life on the back of that. Plus, he’s got a new whodunnit movie out soon, right? So, good heavens…

LikeLike

BTW, I wrote a piece on Charade myself some years ago. You can see it here: https://livius1.wordpress.com/2014/05/22/charade/

I hope it’s not bad form putting in links like that?

LikeLike

Bad form, nuthin’! Such a fine review deserves to be linked above, so I’ll add the link to the end of my own inferior ramblings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much too kind, but thanks.

LikeLike

Among its other notable qualities, well described above, “Charade” is also notable as the cinematic farewell for the star personas “Audrey Hepburn” and “Cary Grant” — not for the actors themselves, who went on to make more movies (though for Grant, only two more, and those relatively insignificant), but for the charming, irreplaceable onscreen creations whose presence audiences loved to share. Still, I hope @JJ can eventually become convinced of her skill as an actress, because it’s there in everything she did (otherwise that star persona wouldn’t have held together convincingly). For clear examples, I’d suggest the earlier “The Nun’s Story,” a serious and straightforward drama; and the later “Two for the Road,” my favorite of all her performances (and one of my top all-time favorite movies) and owing little to the “Audrey Hepburn” star image. (And again benefiting from the work of Stanley Donen and Henry Mancini.)

LikeLike

I watch so few films these days, it’s unlikely I’m going to change my mind about Hepburn any time soon — but I love her all the same, in despite having misgivings about her acting. If it’s any consolation, I don’t really rate Gregory Peck, William Holden, Rita Hayworth, Joseph Cotten, Katherine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, and a bunch of other stars of classic-era stuff (I just think film-making at the time required different things of its stars, and the results don’t stand up over time) — but they all compel the hell outta me, and I’d happily sit through any and all of their performance without so much as a word of complaint.

LikeLike

A wonderful movie and one of my favourites. Your review really sums up all its strengths. Too bad that Donen’s later attempt at a similar type of movie “Arabesque” fell rather flat.

Also love Walter Matthau in this, it just shows what a versatile actor he was. He starred in the excellent “Mirage” too which coincidentally was also written (or in this case adapted from a novel by Howard Fast) by Peter Stone.

LikeLike

This and Pelham 123 really made me re-evaluate Matthau as an actor; in my youth he’d been in the likes of Grumpy Old Men and the one where he’s Einstein with Meg Ryan and I was blown away when I saw Pelham and just how (for want of a better term) Gene Hackmanian he was.

LikeLike