In the most recent episode of our podcast, I mentioned how Agatha Christie’s The Moving Finger (1942) was the book which made me appreciate how threatening a poison pen campaign could actually be. And four years after Christie used the conceit to drive a town mad, surprise Crime Writers’ Association member Enid Blyton made it the background for some childhood japes. What fun!

We start once again with poor, youngest Find-Outer Bets waiting for everyone else to returns from boarding school — it has to be said that to woke, early 21st century eyes the amount of assumed privilege in this book is frankly astonishing — that they may hopefully stumble upon a fourth mystery to solve. And the novelty this time around is that when a mystery does fall into their laps they first need to penetrate the mystery of what that mystery is since everyone — their parents (taking a sudden an unexpected interest in the lives of their children), the Hired Help (feeling that the topic under discussion is Not For Your Eyes Or Ears), and of course the policeman Mr. Goon (who, you feel, might be the Professor Snape of this series when I consider how I’d struggle to deal patiently with such a group of self-satisfied youngsters) — seems keen to keep the details away from them, despite their previous successes in this field.

Although — spoiler in the title — when it turns out to be a tide of poisonously spiteful letters, the Find-Outers are again struck by a previously-unconsidered difficulty beyond simply finding out who is sending them:

“[I]t’s no use looking for footprints or cigarette ends or dropped hankies or anything like that. There’s just nothing at all we can find for clues.”

Indeed, the genius of Christie’s take on this is that her eventual solution hinges specifically on the absence of a clue; such subtleties are possibly lost on Blyton’s younger audience and so some manufacturing of Things to Do is needed, and a delightful sequence ensues in which Pip and Bets try to outdo each other in Fatty’s eyes as having the best idea.

Pip did not look too pleased. He always thought of Bets as his baby sister, and didn’t want her to receive too much praise.

Once again, it’s the realisation of these children as children which really makes these books. The petty jealousies, or the “patient but rather tired voice” in which Fatty must explain to Pip why a scheme he has suggested won’t deceive Pip and Bets’ mother for even an instant. In fact, I’m starting to think that Pip might be the Idiot Watson of the group, since he’s especially thick-headed here — possibly giving Blyton an excess of opportunity to explain things to her readers, yes, but also simply missing the point by an at times Olympic record distance. See, for instance, the moment Fatty claims they can go and speak to the Hilton’s neighbours (pleasingly for me, the very same neighbours from the second book in this series, The Mystery of the Disappearing Cat (1944) — a triumph of in-universe continuity) under the guise of looking for Pip’s lost cat Whiskers — who, one feels, is as surprised as we are to learn of his own existence — and Pip seems unable to grasp how Whiskers can be lost when he’s sitting in the room while they’re having this conversation. Don’t drink during pregnancy, ladies. You’ll get a Pip Hilton if you do.

We get, too, what feels like a real shift in societal attitudes when it’s revealed that Gladys the Maid has received a letter dredging up her recidivist parents, and the fact the she was separated from them after being raised to steal things for them and so spent her formative years in a Home. Because, well, no doubt there were — hell, still are — elements of society who would look down upon the poor girl and cast her out with barely a backwards glance, and yet here’s Blyton offering up what 15 years earlier would have been no small controversy as the backstory for a sympathetic character in a children’s book. You can take either way the Find-Outers’ response to Gladys’ story — “The children were horrified that anyone should have such bad parents” — and it’s interesting that the only other letter whose contents we learn feels a marked step down in severity from this, but I like to see the inclusion of such a story something of a small step towards a widening awareness and social acceptance of those who don’t have it quite so good. More power to Blyton’s elbow.

Once Pip and Bets dream up their separate schemes, and good schemes they are, we get a full chapter devoted to their failure and Pip’s gloomy reflection when they have to tell Fatty that “I expect he’ll think we ought to have done better. He always thinks he can do things marvellously”. And yet Fatty is generous and gracious in their failure in a way that made me feel a little weak inside — how we’ve come on from seeing him as the priggish, unparented, rich boy from earlier cases is a joy to my old heart. Sure, “privately each of them knew that without Fatty they couldn’t do much. Fatty was…the real brain of the Find-Outers”, but this is no Fatty Hegemony, and seeing failure as simply something that happens, and being so inclusive when it occurs, is one of those lessons we need to learn; seeing this group of wonderful characters learn it makes me very happy, especially as is skated over with a lightness that an old pro like Blyton can bring to her writing when it’s needed; she doesn’t get enough credit for how light a touch she can employ at times.

The detection is solid here, too. With the letters being posted from a nearby town, and the only means of getting there being an occasional bus service, a very enjoyable sequence sees the group taking the bus and quizzing its passengers — though any professional detective would be aghast at how much faith they put in what they’re told (the argument is made elsewhere in this series, I believe, that adults are less likely to lie to children…but, c’mon!) until there’s a convenient time to not trust someone. Still, the process followed is fun, believable for the characters involved, and shows just how far society has developed that you can be certain someone would catch the 10:15 bus in order to make the 11:45 post collection…and, hey, Freeman Wills Crofts used these certainties just as rigorously (one chapter of The Hog’s Back Mystery (1933) is predicated on this precise principle) and it leads to some very enjoyable writing, so I’m not necessarily suggesting the development has entirely been for the better…

The lack of any definite physical clues results in some creative thinking when it comes to narrowing down suspects, and Blyton does a superb job of giving us a likely bunch and then clearing all of them from suspicion. The means employed here are again show a large scale thinking where the likes of different privileges involved — that someone could reach adulthood and hold down a steady job without knowing how to read or write, for instance — and I’m much more a fan of this sort of “clear everyone” approach on the way to finding the culprit than I cam those sort of less rigorous “Well, it could be anyone and now we’ve found a single, vital clue we know which one it is” mysteries. The way this exclusion is reversed to identify the guilty party is actually a little bit genius, and the only real shame is that the clues which enable them to do so are dropped in out of stark nowhere…though, in fairness, Blyton has been preparing you for this throughout, and it’s a very cheeky callback that enables her to get away with this without you minding too much.

The lack of motive is an interesting (non-)development, too, in light of the four other entries in this series that I’ve read having solid and well-motivated reasons behind their crimes. It doesn’t harm the book that there’s no clear reason given — a possibility is floated, but never addressed as accurate or otherwise — and the psychological nature of the crime perhaps befits such an uncertain conclusion. It could even be argued that, when the culprit is identified, the very nature of their character and the seemingly contradictory fact of them being responsible for the letters is enough of a conundrum to bow out on. Nailing it down with any single sentence to justify it — “And I did it because of the time when he said I had an ugly cat…well, I showed him!” — would possibly reduce the impact and unpleasantness of what went before. Who knows? Doesn’t happen, so doesn’t matter.

So another delightful entry in this series, and another opportunity for me to reflect in wonder at how thoroughly the Find-Outers seem to’ve drifted well and truly under the radar of the detection-loving set. The logic is sound, the development of the plot well-paced, the actions open to the cast of children realistic (for the setting…), and the eventual resolution satisfying and well-reasoned. Oh, and there’s an inverted impossible crime when Fatty manages to disappear from a locked room using the method described in The Mystery of the Secret Room (1945) — and possibly another one if you want to include the Vanishing Butcher’s Boy Mystery. All told, it’s a joy, and difficult not to recommend this series if you have even a fledging interest in novels of detection at any age.

In fact, the only negative point of any note — and I’m sorry to be a martinet about this — is the Ghastly Americanisms which have crept into my 2016 Hodder edition. At least, I’m assuming they’ve crept in and weren’t in the early editions of the text, and so a brace of queries if you have an earlier edition of this. Firstly, is chapter 15 called Fatty Makes a Few Inquiries? Since that should surely be ‘Enquiries’ — ‘inquiry’ is used throughout, and I’ve come to understand that’s the American option. And secondly, is the final line of chapter 18 “It’s him that done that — I’d lay a million dollars it was. Gah!”? Because, y’know, England in the 1940s wasn’t on the dollar…so surely ‘pounds’. If they have indeed been changed, I’d love to know why an English edition of a story by an English author published by an English publisher is so Yank’d up — it just seems a odd choice to me, but I apologise if it turns out Blyton herself was simply very fond of Americanisms.

None of this detracts from the plot, and I’d hate to appear to have an anti-American bias — yo’re a wonderfl people, despite yor crios relctance to se the letter ‘u’ — it’s just a source of bafflement to me in much the same way as Mr. Goon talking about a million Rupees would be. Any clarification would be greatly appreciated!

~

The Five Find-Outers series:

1. The Mystery of the Burnt Cottage (1943)

2. The Mystery of the Disappearing Cat (1944)

3. The Mystery of the Secret Room (1945)

4. The Mystery of the Spiteful Letters (1946)

5. The Mystery of the Missing Necklace (1947)

6. The Mystery of the Hidden House (1948)

7. The Mystery of the Pantomime Cat (1949)

8. The Mystery of the Invisible Thief (1950)

9. The Mystery of the Vanished Prince (1951)

10. The Mystery of the Strange Bundle (1952)

11. The Mystery of Holly Lane (1953)

12. The Mystery of Tally-Ho Cottage (1954)

13. The Mystery of the Missing Man (1956)

14. The Mystery of the Strange Messages (1957)

15. The Mystery of Banshee Towers (1961)

I can’t help you with the Americanisms, sorry, since I only have these books in the Swedish translations, but I can tell you that the translators easily skirted this issue in chapter 18 by not mentioning any denomination at all: “I’d bet a million on it”. 🙂

This was one of my first three books in this series (“Disappearing Cat”, “Spiteful Letters” and “Vanished Prince”), and therefore it holds a very nostalgic place in my heart. I remember this with a lot of fondness and can’t find much negative to say about it at all.

And the very beginning is really funny with Fatty disguising himself and fooling old man Goon completely.

LikeLike

Well, they don'[t have money in Sweden, do they? Everything’s free. So any mention of currency would confuse the poor young Swedes and start the entire county on the path to financial armageddon.

I have nothing negatie to say about the plot or the manner of its unfolding — it’s lovely, in fact, to see Blyton taking on a different type of mystery where the way to proceed is so nebulous and abstract. It’s difficult to do that, and to have the parents wishing to shield the children from it, while also having the plot progress in a meaningful way.

Man, I sm so enjoying this set of books. Sure, there’s gonna be a duff one at some point. That’s fine. For what she’s done in these opening volumes, Blyton has earned my patience as well as my GAD-loving respect.

LikeLike

The plot to erase British spelling has been carried out methodically over the years with supreme care. It began with Operation Past Simple. So far, we Yanks have scored a victory by destroying the ghastly ‘lighted’ (elegantly repeating the participle ‘lit’) and made progress in ed’ing ‘burnt’ and ‘learnt’ out of existence. By next year, ‘got’ will be gone, replaced by ‘gotten’ and forever changing the phrase, “Have you got any pocket money?” to a more utilitarian “Do you have…” Before you realize it (with a ‘z’, not an ‘s’ or a ‘zed’) you will recognize our spelling as the correct one and apologize with good humor.

LikeLike

I always assumed that the -t end to past participles was the AmericaniZed version. Consider “spelt”, which is a grain in my house (well, no, it isn’t, on account of my gluten intolerance), vs. “spelled” — surely only the English mind could cope with such distinctions. Americans only have one “practise” after all…

I think I just like The Old Ways. I write about “clewing” after all, and read books relying on obscure principles from the 1930s (party telephone lines, entails, cranking handles for cars) for fun. And all this new music makes my ears hurt. Ouch, my knees…

LikeLike

Americans avoid “gotten” in writing – they think it’s low-rent.

LikeLike

I can’t keep up any more; I’m just going to write everything in Victorian English from now on.

LikeLike

My 1988 Armada edition also has “inquiries” and “million dollars”.

I read a few books of this series in Portuguese when I was a child; I reread them a few years ago and had to get all the others, this time in English.

LikeLike

Huh, good to know — thank-you. Can anyone go earlier than 1988?

It amazes me to hear so many people knew of this series — well, no, it doesn’t amaze me they knew of it, since Blyton is a hugely popular author and they’ve been republished a number of times. It amazes me that these books weren’t more discussed in the fandom of classic mysteries; they’re textbook examples of how to write this sort of story, and even the impossible crimes are workable. I would have been raving about them from the rooftops!

LikeLike

This is the first – and only, so far – Find-Outers mystery I have read (thanks to you, JJ!), and I thoroughly enjoyed it, as my own review will bear out. Subsequently, I have gathered together nine or ten more titles and, in the ways of a GAD hoarder, have read none of them yet. But just you wait, my pretties. The time will come when I enter my second childhood and have the leisure to savour these.

So about that British “u” JJ: I wrote savour for you . . . and my computer promptly underlined it in red. That red line . . . whoa! It’s doing my OCD no favours. Oh, God! There it goes again . . . We Americans are trained out of using the “u” through Word and Google and all things American. It can’t be helped. Perhaps if I dictated my responses to my secret-tree . . . or, is that a desk?

Never mind: we cut out all the “u”s, and you Brits refuse to say the letter “r.” It’s a fair exchange.

LikeLike

I was at a secondhand book market over the weekend and there were about nine or ten of the Find-Outer books there, and I had a moment of dearly wishing there was someone I could buy them for. Then I had a few moments of “Well, I don’t own these particular editions…” but managed to shake off that notion. Multiple Crofts, Carr, Gardner, Christie, Rawson, etc should suffice for now. Best to leave those Blytons for someone else to find and love.

As for Americanizzzzzed spellings, I’m aware that I’m three steps away from writing a letter to my local paper when I sigh a little inside at the incidents of “realized” or “pants” or “butt” or “pajamas” that seem to be invading British versions of books. I’m aware the English language is a flexible thing, and I know the prevalence of TV and movies has a huge cultural impact…but, like, spelling, people — c’mon.

Anyway, it shall continue to happen whether I gripe about it or not. Time to pick another fight I can’t influence and won’t win.

LikeLike

Well, if British spelling is influenced by American spelling, get ready – because it seems like America is doing away with spelling altogether. I blame it on texting and the fools on Twitter, many of whom are either Kardashians or leaders of the free world.

LikeLike

I know, right, all these young people with their texting and their jitterbugging and baggy trousers. With all the mumbled lyrics in their music and no-one releasing CDs any more with booklets containing the lyrics, it’s no wonder none of them can spell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Publishers probably update for American editions – and then that becomes the text. There was a moment when vintage children’s books were updated with “2.5 new pence” instead of “sixpence” etc.

LikeLike

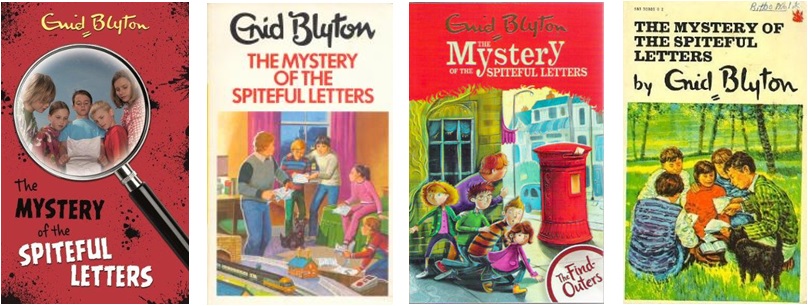

I’m not familiar with Enid Blyton except as a kids’ author I missed when I was a kid, but I’ll have to check this one out, in spite of now being way older than her target audience. I’m struck by what all those covers, from the cartoonish to the realistic, have in common, namely the font used for the author’s name… I guess Blyton got to be so big her name became a trademark, kind of like Walt Disney!

LikeLike

Y-you say that like I’m not older than her target audience… 😉

That’s a great point about her signature/name font, I hadn’t recognised that. The same is true of Agatha Christie, too, since British (and I’m sure international) editions of her books have the same looping-A-Agatha font which must be a signature, now doubtless trademaked and copyrighted up the wazoo. Any others anyone can think of?

Anyway, my definitely-adult self can highly recommend these titles, and the detection community that hasn’t yet got on board with Blyton as one of our own needs to do so sharpish!

LikeLike

Speaking of the covers, I think the ones you’ve included above are fine, but very obviously directed towards children.

In Sweden, the Find-Outers have been published in four distinct variants. (Not editions, because there have been more than four of those, but four different versions from three different publishers with distinctly different covers.)

On this site, http://www.monsterashistoria.se/mysterie.htm, all of them are shown, as well as the first English edition. I think the second Swedish variant is by far the best, even compared with all the English covers I’ve seen. I don’t think anyone would mistake them for adult mysteries, but they’re not as obviously directed towards children as are the English ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love those first Swedish variants, with the single-colour backgrounds and line drawings — they’re beautiful. Man, some old-style cover art is so goddamned amazing; it really hold up over the decades, hey?

With an interest in well-designed mass produced paperback covers rising again, let’s hope that in 50+ years we’re able to look back on some of the superb work being done now — mostly, admittedly, on reprints — with as much enthusiasm.

LikeLike

Inquire is not an Americanism. I looked up Fowler on the subject of ’em- & im-, en- & in-‘ and it reads:

‘Tenacious clinging to the right of private judgement is an English trait that a mere grammarian may not presume to deprecate, & such statements as the OED’s “The half latinized ‘enquire’ still subsists beside ‘inquire'” will no doubt long remain true.’

Also see ‘A Murder is Announced’.

Possibly dollars is what Mr Goon says in his character of a vulgarian.

LikeLike

I…don’t even know what that means, but I’m interested to learn it isn’t an Americanizm. Who is Fowler, by the way?

LikeLike

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Dictionary_of_Modern_English_Usage

LikeLike

Ah, so the (English) precursor to Strunk & White. Nice.

LikeLike

Solution to the “dollar” question?

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/dollar

About halfway down the page, we have this definition: “British informal: (formerly) five shillings or a coin of this value”

LikeLike

That…that actually sounds pretty reasonable, hey? Superb research! This will teach me to jump to conclusions (well, no, I don’t need any help with that…but you know what I mean).

Thank-you, genuinely, for passing this on. I’m fascinated and shall research further.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, definitely her name written that way (imitating her actual signature) became a distinctive trade mark. It’s in the Spanish editions of her works too, and as a child when I saw a book in the book shop with that signature, it was like a promise “there’s a good story inside”. I was quite sad a few years later when I discovered that Enid Blyton had died a decade before I was even born. Rest in peace, Enid, and thanks for all the adventures.

LikeLike