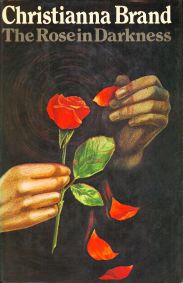

I don’t think I’ve ever disliked the cast of a novel as much as I disliked the core group of The Rose in Darkness (1979) by Christianna Brand. Goddamn, what a bunch of self-centred, self-congratulatory, self-satisfied, smug, pretentious, vacuous, condescending, poseur, low-rent hipster prigs. You say ‘bohemian’, I say ‘unbearable’ — were people really like this in the Seventies? And, because Brand does her usual thing of telling you up front that there’s one victim and one killer, you know that once the body turns up you’re stuck with the rest of them until the end. Good heavens, there’s never a serial killer around when you need one.

As with most of Brand’s work, the story here revolves around a tight-knit group into which murder insinuates itself, and then things become rather muddied by who was where when, the lies most of them are willing to tell, and the relationships that get challenged and reversed along the way. This a familiar furrow for Brand and, for the most part, the people involved work as sympathetic portraits of any one of a number of general types placed under unimaginable stress while also dealing with people they’re very close to and must necessarily suspect. It’s a well-worked seam in mystery fiction, and Brand, while falling down in other regards, doubtless returned to it so frequently because, frankly, she worked it better than most. Except now, nearing the end of her career, she’s moved on with the times to introduce the Bright Young Things of the 1970s and has failed to notice that the people of Brand’s 1970s seem to lack any redeeming features at all.

How do I loathe thee? Let me count the ways…

First up, the casual racism so readily accepted in the era is massively uncomfortable — “I can’t be doing with these Paks, their nails so pale at the ends of their fingers!” might be a deliberate piece of character unpleasantness, but the cloth-eared admiration of “They do put their hearts into [studying], these black chaps, don’t they? You’ve got to respect them” offered up by Chief Inspector Charlesworth is awkward and wrong is so many ways — but, as I’ve said before, we must always remember that times have not been so enlightened (though, it may be argued with an eye on recent world events, that times now aren’t even all that enlightened). And, sure, while by my own argument it’s possibly wrong to hold this against the book, given that Brand tries to be even-handed about it, the utter “down with the kids” attitude adopted is — despite the admirably cosmopolitan attitude taken towards homosexuality — the equivalent of virtue signalling and feels about as comfortable.

Secondly, another odd writing choice of Brand’s, is the way phonetic rendering of certain words will turn up again and again: “dellycatessing” and “chicking sangwidges” and “restrong” and “ap-solutely” — it’s possibly how people might speak, but added to the self-satisfaction of everyone involved it comes across as horribly false and cutesy. Then, thirdly, you add to this the brilliance with which one-time movie star Sari Morne views herself and everyone of her Eight Best Friends, and you find you’re just stuck in a book of dullards whose author thinks they’re charming and free-spirited and young and wonderful. But when Sari herself characterises one of her friends thus:

[Charley] was in fact an intensely boring young man; but they loved him because never, never, never was he bored himself, so deeply and devotedly was he interested in all that concerned these wonderful people among whom..he had found himself a place.

I’ve a feeling that you’re gonna face a lot of ridicule for this so I’ll come in first to say that I’m with you. I read this along with a few other Brands many years ago and disliked them for the simple reason that good writing and wonderful characterization can’t substitute for clewing and the puzzle-plot.

I had the same problem with ‘Fog of Doubt’ when I tried it last year. I should clarify that I haven’t yet read ‘Green for Danger’ or ‘Death of Jezebel’, apparently her best work but unlike many others, Brand is not in my first tier of GAD authors.

LikeLike

I would recommend trying Suddenly at his Residence, Neil. I think that is another really strong one by Brand, and I think JJ thought so too. Equally it is far easier to get a hold of than Death of Jezebel.

LikeLike

I second that recommendation.

If you are fortunate enough not to live in a certain backwards country, all the books are available in Kindle and ebook.

LikeLike

Agreed; I second these recommendations.

LikeLike

I thought ‘Suddenly at his Residence’ was considered to be one of the weaker ones but I’ll try it if you say so. And as Ken said, Brand’s entire ouevre is available on kindle pretty much everywhere apart from UK, so availability is not a problem!

LikeLike

Brand as a writer — sentence by sentence — I would put pretty near my personal pinnacle. As a plotter, and as someone who sustains an unflagging interest throughout a narrative…no, not so much. And when she gives you people this unlikable, too, it makes it even harder.

But, hey, I’m not writing her off, before anyone goes accusing me of that. I’m just always going to take her one piece of work at a time — which, in fairness, is probably how we should treat authors, since we usually end up with a cavalcade of caveats otherwise (“Oh, Carr’s wonderful…so long as you don’t mind the dip between April 1952 and June 12th 1968 at 4pm…”)

LikeLike

Good grief! You all act as if you and Neil are dressed in black, assault rifles at the ready, encircled in the warehouse district by the heathen mob that worships Brand as a goddess!!

No real reaction here. We in the blogosphere placed bets on how much you would vilify this, and I won first prize: $13.20 and the entire Nigel Morland canon. So no complaints here! (I sold the Morlands and got another $3.32!!)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Delighted to have won you some money at last; I know you lost heavily on Ben’s feelings about Ellery Queen, so thankfully one of us has come through for you…

LikeLike

This is one of those cases where my brain just can’t resolve the different experiences that we had with this one. As you could tell from my gushing, I loved it and it’s a book that I think everyone should read. It’s unfortunate that you didn’t share the experience that I had with the book – the ending in particular was striking.

I agree that this isn’t the same sort of likable cast that Brand has provided in the past, although I don’t see her as intending them to be. The characters are indeed selfish, childish, and shallow, as I think Brand intends them to be viewed, but she still graces them with a humanity that leaves the reader somewhat conflicted. And although this doesn’t share the “how can one of these people be the killer?” horror that Fog of Doubt possesses, I have to think you still felt that the ending was an emotional rollercoaster.

I get a sense from your opinion of The Rose in Darkness, Fog of Doubt, and possibly (?) Green for Danger, that you dislike some aspect of detection in these books. That’s the part that I’m most curious about. There is an investigation here, both by Sari and her friends, as well as the inspector, although it isn’t handled in the standard sense of detective fiction. At the same time, I don’t believe that you’re fixated on the need for a detective to detect, so I’m just curious about what element you see missing in these books.

LikeLike

Taking then one at a time:

Green for Danger — my memory of this is that every time there’s a crime or suspicious event, everyone sits around discussing at great length and with a seeming absence of concern, how very possible it was for anyone to have done it, and then Brand plucks someone at random to be guilty. I’m reliably informed that’s not the case, and shall check out the book again in due course, but I did come away with that feeling uppermost when I read it pre-blog. This frustrated me at the time because of the favourable Christie comparisons I’d had ringing in my ears at the time, and an absence of any clues or indication of what was to come struck me as thoroughly un-Christie and a complete, lazy cheat. Expect an update when I read it again.

Fog of Doubt — here, every time (and, no, I’m not imagining it, since I paused to write up my thoughts after each chapter) an event is about to be revealed that will provide any clarity at all, Brand cuts away from it. Every. Time. To be shown nothing for the entire book is to be left thoroughly unable to engage with the meaning of any actions or to fit anything into a meaningful context. And I hate having that disclosure snatched away at every turn.

So, yeah, nothing about the detection as such. It’s always something different each time I dislike a Brand. Which is part of the fun — what will it be next time?!?!

LikeLike