Something a little different this week, potential threats of legal action notwithstanding.

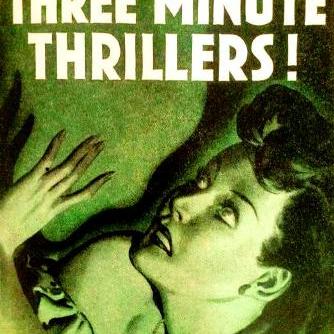

Nigel Morland is a name that crops up a lot in my researches around potential classic crime fiction, even if “Nigel Morland” is not necessarily the name that crops up — he wrote rather prolifically under that handle alongside pseudonyms as diverse as Mary Dane, John Donavan, Norman Forrest, Roger Garnett, Neal Shepherd, and Vincent McCall. As of yet I’ve not tried any of his novels, but seeing him listed in Locked Room Murders (1992) I picked two short stories from a collection with the intriguing title 26 Three Minute Thrillers! (1946) and dove in.

In short, these are one-page, 500-word stories featuring the amateur sleuth Mrs. Pym who enjoys some success in the opening tale and is then drafted in to help with some baffling crimes when the police get into trouble (so, your classic AD, then). And, in the grand style of Encyclopedia Brown — er, who these predate, so pick a less anachronistic example, like The Baffle Book (1930), which wouldn’t occur to me — after the problem is presented to the reader you’re told that the answer is in the back and to think it over, try to deduce the answer, and then turn to the back to see how wrong you were.

Because, you will be wrong. Not on account of the brilliance with which Morland hides clues in plain sight, but because these are — in fairness, called thrillers on the cover — possibly some of the most hilariously unfair stories put in this form since, er, well since The Baffle Book.

Y-yeah, sure thing, guys.

So, just for shits and giggles, I thought I would replicate the two stories here and then provide a link to the solution as given in the book. The reader is a) warned of the unfairness of the ensuing tales, b) invited to suggest solutions that would also fit the given setups, and c) apologised to if this seems like someone taking liberties by reproducing the entire texts. In my defence, the collection is very OOP and my researches lead me to believe that I’m reasonably secure in reproducing these, but I will of course take them down if anyone wishes to raise the aforementioned threat of legal action. I should probably say that I really like the format of the book, and Morland writes well to set up interesting, if basic, puzzles. There’s some good imagination on display here, so let’s not begin proceedings under the impression that I’m here to put the boot in. Quite the reverse.

And so, without further ado:

THE PHANTOM KILLER

There is a place on the Cornish coast where the surf-riding is the best in the country. But Mrs. Pym was no bather, for she was stolid and not over-young; she preferred to sit in a deck chair.

The late afternoon sun was making her sleepy. Then a burst of shouting brought her out of the chair and saw people were carrying [sic] somebody up the firm sands. She joined the excited throng, watching them work on a man lying on his back.

A good-looking man in a bathing suit stepped back in horror.

“Dammit, he’s dead!”

It was not Mrs. Pym’s place to take charge; she did it just the same. She gave her name to the constable who arrived and he stood back in awe. The good-looking man, whose name was Kerruish, gave her the details in an undertone.

“His name’s Spencer — Johnnie Spencer. He and his missus came down here with my wife and I, and annual affair. He’s as healthy as a dog. We’ve been surf-riding for the past hour, then, suddenly, he gave a sort of a yell and fell off his board as if he’d been knifed.”

Mrs. Pym liked Kerruish. He was quick-thinking, observant and sensible. Under her examination, he thought nobody had been near Spencer; but something had happened. He was not drowned, and his queerly contorted body suggested a poison, which the local doctor confirmed at sight.

There seemed no reason why a comfortably placed, happily married executive on holiday should die in that queer fashion.

In a little circle on the beach, Mrs. Pym, Kerruish, the doctor and a police inspector went over the facts again. The most extraordinary evidence was when Kerruish said he and Spencer had been away from their hotel since dawn. They has eaten nothing but hard-boiled eggs, apples, chocolate, and bananas, an alarming if harmless mixture bought from a kiosk on the beach. The doctor had never heard of a poison that could have been administered something like twelve hours before at the hotel; the food was considered entirely innocent. Their only drinks had been mineral water.

It did not satisfy Mrs. Pym. She could see that Kerruish was likely to be under suspicion, and by the time the wives had returned from Truro, where they had gone for a day’s shopping, it seemed as if he would be under arrest.

It was a question of scrutiny and guess-work. Mrs. Pym dropped on her knees and examined Spencer’s body in the little hut to which it had been taken. She examined his bare chest, revealed by the turned-down blanket, and his surf-board, his towel, the bathing-suit removed from his body by the doctor.

That evening it took her ten minutes to get the truth. After the police had made their arrest, she told Kerruish what had happened.

See, I love that “It was not Mrs. Pym’s place to take charge; she did it just the same” and the classifying of their food over the course of the day as “an alarming if harmless mixture” — how goddamned charming is that? Also interesting to note the potential there must surely be for beach-set impossible crimes…beyond all-time classic ‘No Killer Has Wings’ (1961) by Arthur Porges and the better-forgotten ‘The Sands of Thyme’ (1954) by Michael Innes what else is out there?

Anyway, you can find the solution to this one here, and some very nice ideas it contains, too. Onto the next:

THE IMPOSSIBLE CRIME

The office had waited an hour over the time St. Barbe Mitchell had insisted he would require to finish recording his speech. In the end uncertain men knocked and knocked again on the office door, then, with managerial authority, the lock was forced

The general manager of the National Planing Committee wasted no time. He recognised hydrocyanic acid when he smelt it, and got on to Scotland Yard immediately. It was the evening of St. Barbe Mitchell’s radio speech when he was to give his long awaited Blueprint for the New World over the air. his death was not natural, and the crime so horrifying that it was best to seek the highest powers instantly.

Mrs. Pym, who was linked in the public mind with the gift of solving insoluble crimes, was rushed to Grosvenor Square in a fast car with Chief Detective Inspector Shott for company.

She found the National Planning Building in a furore. St. Barbe Mitchell had been chosen to create order out of economic chaos, and this was the night before his report — the conclusion of eighteen months intensive work. And he was dead.

Cardew, the general manager, Mitchell’s secretary, Peller, and the chief secretary, Baines, received Mrs. Pym in the main hall.

“It’s absurd!” Cardew burst out. “Mr. Mitchell went in alone and locked the door behind him. It’s been under observation by the staff ever since, and yet he’s dead!”

Mrs. Pym nodded, and stumped into the fatal room with a dozen people watching her.

The office was perfectly plain. It contained a bookcase, a carpet, a table bearing a blotter, pencils and paper. Next to this was a dictaphone, and that was all. The windows were locked, and heavily barred; even the plain walls were without pictures.

The doctor was there, shaking his head.

“I can’t understand it,” he said mournfully. “The man’s swallowed a big dose of hydrocyanic acid; it killed him immediately. There’re traces in his mouth, so that rules out a capsule. There isn’t any cup, or anything from which he could have swallowed the stuff.”

And so it proved. There was no hiding place for a murderer. The bare room showed nothing from which poison could have been taken, even if Mitchell had lived long enough to hide the evidence. As a locked room mystery, it was unique.

Mrs. Pym bent over the dictaphone and, after examining it, moved the needle and pressed the stud to set the machine in motion. She listened to Mitchell’s speech, noting the sudden gasp when he broke off almost at the first words.

It was bizarre. Her investigation proved the crime could not have happened, yet the contorted body was there as proof. Finally, she asked for a list of every person who had entered the office that week.

These examples are pretty horrible for withholding information that, if included in the story proper, would at least have resulted in a fair experience. But I have to say I’ve always been a fan of these short, one-page mystery “stories” (quizzes). The Dutch Disney comics has had a semi-regular one page mystery series since at least the late eighties, nowadays starring the Mouse himself. Sure, they are simple, but they are always fair (usually visual clues) and quite entertaining. I was actually quite surprised to come across a newly released collected volume of these Mickey Mouse mysteries only last week at the local kiosk, meaning even now, a kid’s first introduction in proper mystery fiction might be the Dutch Donald Duck weekly.

(A short piece on the European/Dutch history of Mickey Mouse as a detective figure: https://ho-lingnojikenbo.blogspot.com/2018/02/might-solve-mystery-or-rewrite-history.html )

LikeLike

The experience of “the solution is in the back” has been, for me, largely an exercise in How Authors Don’t Play Fair, but I’m sure some very good examples exist (Rich posted a few back when Past Offences was a going concern still), The “fairest” seem to be those that rely on mathematical principles, but it’d be nice to find some that were legitimate deductions rather than certainties.

So, what I’m building to saying is, these Dutch Disney comics sound delightful — thanks for the link, I’ll check out what I can.

LikeLike

“Also interesting to note the potential there must surely be for beach-set impossible crimes…beyond all-time classic ‘No Killer Has Wings’ (1961) by Arthur Porges and the better-forgotten ‘The Sands of Thyme’ (1954) by Michael Innes what else is out there?”

John Dickson Carr’s “Invisible Hands” is beach-set impossible crime story with a no-footprints problem and there are a couple of them in the Case Closed series.

“The reader is… invited to suggest solutions that would also fit the given setups”

Well, the premises don’t allow for much wiggle room to wedge in an alternative solution, but have two (shaky) alternative solutions for “The Phantom Killer.”

There are two other ways Mrs. Spencer could have poisoned her husband: before going into the water, she could have pretended there was a bug or mosquito on his back and pretended to slap it. But what she actually did was pricking him with a tiny, poison-coated needle she held between her fingers as she pretended to slap the imaginary bug. However, you have to change the location of the puncture wound from the chest to the back.

The second method is hardly credible, but here it goes. Spencer could have been in the habit of rubbing an apple against his chest, before taking a bite, which his wife knew and could have carefully handed him an apple with that tiny, poison-smeared needle sticking out – which he might even swallow without noticing it. Something that could have been a clue when the pathologist finds it. Of course, this would probably result in a scratch instead of a puncture mark. So probably works better as a false solution that can be demolished.

There’s only one solution to the premise of “The Impossible Crime.”

LikeLike

Nice work, and you’re probably right about ‘The Impossible Crime’ — as soon as someone has to put a doodad up to their mouth you know full well that it’s going to shoot a poison at them. It would be nice if there was sufficient space for this to be offered as a false solution and something else to be cooking in the background, but the setup is pretty stark.

There’s a nice variation on this — given the era, and all — in Robert van Gulik’s The Chinese I Forget Which Noun Murders.

LikeLike

Beach set impossible crime? How about The Witch Of The Low-Tide by someone you might well have heard of…

LikeLike

Ha, nice. Knowing my luck I’d’ve assumed that was something on a beach and Carr would do a Burning Court on me — y’know, that novel of his that’s most assuredly not set in a courtroom (but, weirdly, features a courtroom on the cover of at least one edition…)

LikeLike

Also, I should say, if anyone wants to bring up ‘The Flying Death’ by Samuel Hopkins Adams…please don’t. That makes ‘The Sands of Thyme’ look like a subtle masterpiece of genius insinuation.

LikeLike

Oh, and not Golden Age, but Paul Doherty’s The Song Of A Dark Angel which one-up’s the usual no footprints around a corpse on a beach by having the corpse decapitated and the head placed on a spike. And why not…

LikeLike

Hmmm, sounds intriguing; think I might have a copy of that one somewhere abouts… 😛

LikeLike

The Case of the Gold Coins by Anthony Wynne has an ingenious solution of a dead body found on a beach free of footprints. The ocean tide did not wash them away because they were never there in the first place! The solution requires some knowledge of earth science and a bit of out of the box thinking. It’s probably the best of the Wynne novels, much better than the one that the British Library decided to reprint.

I think you’d like Morland’s books. They lean heavily towards the Edgar Wallace thriller school, but many of the Palmyra Pym books have aspects of fair play detective novel plotting techniques. The John Donavan mysteries are almost all exclusively impossible crimes as are the three Neal Shepherd mysteries. Both sets of books are scientific detective novels with the solutions relying on chemistry, physics, sometimes engineering, and machine designs, too. One of the Shepherd books includes murder in a wind tunnel! Diabolical murder method, the engineering of which went over my head even if it was explained in detail.

LikeLike

Thanks, John, I’m steadily working up to a Morland novel — which is in part why I picked him out of Adey to feature this month despite him not exactly being a big name. I have The Corpse Was No Lady in hardcover, and Amazon has The Case of the Rusted Room on Kindle, so there ar options to explore his work a little deeper. I’m intrigued to see what I find.

Thanks for the Wynne title, too. Interesting that the BL haven’t returned to him yet, given that they seem quite keen on repeating authors – cf. Crofts, Bude, Lorac, Symons, Burton, Farjeon, Bellairs, Melville etc — ad so many of Wynne’s books do sound rather marvellous. It’s to be hoped that there aren’t the Carr-degree rights problems and that we get more from Wynne at some point; I liked Murder of a Lady without loving it, and would greatly appreciate being able to see more of Wynne’s very entertaining-sounding work.

LikeLike

There’s yet another Carr story set on the beach: “Error at Daybreak” from the Colonel March series.

The Encyclopedia Brown mysteries are scrupulously fair. So scrupulous that they are fairly easy to solve.

LikeLike

Yes, there is — disappointed to forget that one, thanks for the reminder.

I read my first couple of Encyclopedia Browns recently and would love to write about them on here, but I don’t really know how to write about them when they’re so brief. Great fun, so maybe I’ll read a bunch and do some sort of overview, but, sure, they’re also pretty simple given their juvenile market.

Though I did learn that when someone faints they fall forwards and not backwards, which I suppose makes sense but I didn’t explicitly know. So maybe “Things I Have Learned From Encyclopedia Brown” will be a post on here in a few months…

LikeLike

Dark of the Moon features a no footprints on the beach murder as one of its historical backdrop crimes, although it is disappointing in the end. Of course, you didn’t count of your post becoming an anthology of beach impossibilities. Hey – that lake in Rim of the Pit was frozen, but I bet there was a beach under the ice…

LikeLike

Nothing would delight me more than for the comments of this post to become a reference point of beach-set impossibilities — especially if there are more out there not by a certain JDC (because — yaaaaaawn — we’re all so bored of Carr, of course…).

I’ll start: ‘The Seer of the Sands’ in series 4 of Jonathan Creek

And, you may jest about Rim of the Pit, but it raises a philosophical point about this type of mystery: given that both are essentially surfaces that hold footprints, is there any notable distinction to be made between a beach-set mystery and a snow-set one? Each devolves to a No Footprints categorisation, after all…

LikeLike

is there any notable distinction to be made between a beach-set mystery and a snow-set one?

Well shoot, that’s a really interesting question. As you say, these are variations of no footprint impossibilities, which tend to boil down to the ability to detect tracks in the snow/sand. It’s not like any of these are actually solved by taking a print of the shoe – it’s more about determining if it is a big footprint, a small footprint, some device such as a bike or stilt, or a complete lack of footprints. Both snow and sand will show the presence of tracks, and of course they both get obscured over time by factors such as wind, melting, more snow, or tide.

Snow has a distinguishing property of depth – you’re not going to obscure movement through three feet of snow, although the depth also obscures the nature of the tracks.

The beach has an additional element – the neighboring water. Water of course doesn’t hold tracks.

Hey, this is a good excuse for you to finally read Have His Carcase!

LikeLike

The beach has water, and the snow has ice — so we’re all even again.

I also feel that deep marks in snow — if, say, someone uses stilts to cross a snowy plain — remain, where wet sand will likely press in and fill the hole left behind, even if not completely. And, yes, the aspect of tide definitely factors into beaches in a way that I don’t think there’s an equivalent for in snow.

However, both can be moved across without leaving a mark in much the same way; now I’m wondering if there’s an impossible crime story in a method that does work on sand/snow and is reattempted on the other but doesn’t work and so gives the killer/method away…

Have His Carcase is coming…at some point. If ever there was a book I have wildly contrasting feelings over — “Read it now!”/”Oh, dear god, it’s so damn verbose…!” — it’s that one. Gotta just screw my courage to the sticking plate and dive into that one, hey?

LikeLike

I’m wondering if there’s an impossible crime story in a method that does work on sand/snow and is reattempted on the other but doesn’t work and so gives the killer/method away…

One that I can think of is using some other element of the environment (rocks, tree, lamp post, fence, etc) to achieve the lack of footprints – whether attaching a rope or some other method. Snow covers everything, so depending on the setting, it may be difficult to use such an approach.

Here’s another question – what are all of the different “footprint” surfaces (that have been used in an actual story)? I can think of:

Sand

Mud

Snow

Dust (Suddenly at His Residence)

LikeLike

I can’t think of an actual story to use it, but Brad and I once discussed in the comments somewhere a setup involving wet cement/concrete, and I came up with a (if I may say so myself…) half decent way to get a body into the middle of a freshly concreted area without leaving any footprints.

Surely, too, there’s a good environment in low-gravity settings where footprints form more easily. After Inherit the Stars by James P. Hogan, I’ll always be especially keen on the idea of space as a location for an impossibility.

Your comment about other elements of the environments also reminds me that one of the three no footprints murders in ‘Murder at an Island Mansion’ by Hal White takes place on a beach.

LikeLike

Pingback: THE MORLAND CONUNDRUM | ahsweetmysteryblog