Socialising is difficult, isn’t it? One minute you’re making polite dinner party conversation about jobs with someone you’ve only just met, the next a hypnotist performs a few mesmeric passes and goads a wife into stabbing her husband with a knife everyone knows is fake but which — awks — actually turns out to be real and, oh my god, she’s killed him. We’ve all been there, and we all know how tricky it can be to factor this sort of thing into one’s TripAdvisor rating. An unexpected, impossible murder can dampen the mood somewhat — especially when so many people seem to be operating at cross-purposes — but remember you did say the canapés were lovely…

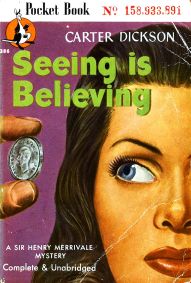

Seeing is Believing, a.k.a. Cross of Murder (1941) — I much prefer the first title, which I believe was used in the U.S., but it’s pretty meaningless — is the twelfth novel to feature the Old Man, Sir Henry ‘H.M.’ Merrivale, and plunges us into this precise social vipers’ nest. In Cheltenham to recite his memoirs to the gifted ghost-writer Philip Courtney — “after matter libellous, scandalous, or in bad taste had been removed, he estimated that roughly a fifth would be publishable” — H.M. is drawn into matters when Victoria Fane stabs her husband Arthur while in such a hypnotic trance, part of the after-dinner entertainment provided by the improbably named Dr. Richard Rich. The only real problem is that everyone present — Rich, Victoria, Courtney’s friend Frank Sharpless, and the lovely Ann Browning — can guarantee two things: first that the knife used was made of harmless rubber at the time it was placed on a table in full view of everyone, and second that no-one went near it except for Victoria Fane…who, Rich maintains, would have been unable to use it knowing it was real even while hypnotised.

The question, then, is not so much howdunnit? as howswappedem?, and despite Courtney’s fears that it will distract H.M. from the task at hand, the Old Man won’t be swayed — “Napoleon could do five or six things at once. I can have a good shot and managin’ two”. This comes from an era in Carr’s career where he produced several tight ‘household’ problems — The Reader is Warned (1939), The Man Who Could Not Shudder (1940), The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941), The Seat of the Scornful (1941), The Emperor’s Snuff-Box (1942) — and, in all honesty, it feels like the least of these. He still has that masterful narrative voice that sets scene and mood in one effortless breath, see:

Courtney, it must be confessed, experienced something like a fit of the cold shivers. The commonplace well-to-do bedroom, like ten thousand other bedrooms in England, made a contrast for depths of violence: for ugly pictures under respectable paint.

And:

The library, you felt, was seldom used. It has a correct air of weightiness: a claw-footed desk, a globe map, and an overmantel of heavy carved wood. The books, clearly bought by the yard and unread, occupied two walls: in their contrasts of brown, red, blue, and black leather or cloth among the sets, even in an occasional artistic gap along the shelves, the showed the hand of the decorator.

I think, although I could be mistaken, the scarcity of this one is due to a lack of reprints. It was overlooked when Pan did a few paperbacks in the late fifties. I think I enjoyed it a bit more than you, but be warned – it’s all downhill from here for Merrivale. Mocking Widow is OK but Crimson Blind… Brace yourself!

LikeLike

It’s interesting with Carr — as with Crofts — to see the same titles cropping up secondhand again and again and again, and then there being either a scramble I’m priced out of when something rare like this crops up, or that rare title being hilariously overpriced despite having the hell kicked out of it on account of its scarcity. I think I’m five Carrs and three Croftses from a full set, and I’m wondering if I’ll ever make it..!

This is a perfectly fine Carr, but both in theme and era it’s down the “hmm, maybe I’ll dash out a quick one” end of things since we know that at this time he was at the peak of his form, and arguably had some of his best work still ahead of him (c.f. She Died a Lady, Till Death Do Us Part, etc). The working of the impossibility feels like the first thing he could think of, and would be laughed out of existence in a book by someone lacking his esteem.

But, hey, character, tone, and essential scheme still go a long way, and we know he could do all that in his sleep.

LikeLike

There are a few books that are definitely expanded short story ideas. I think it’s on record that Wire Cage was a novella that had to have the second murder added to pad the page count. I’m guessing the forgettable final event in The Black Spectacles came from a similar source. This is pretty short as it is, but thank goodness he did pad it out, as if it was just the impossibility…

Are you aware that some people consider the early misdirection in this one tantamount to cheating?

LikeLike

I seem to remember from your review of The Men Who Explained Miracles that there’s some short story in there that had previously been expanded up to a novel — I guess that became de rigueur, given the expectations of output on authors for a few years back then (Christie did it, Berkeley did it, McCloy did it, .I have a feeling Allingham did it, and Brand possibly — if you can’t beat ’em…!).

As for the cheating controversy, yeah, I figured that after a reading a few reviews — see my reply to Nick above (pr possibly below). I find it odd that Carr could have presented that misdirection in a way that was eminently fair and would cause no controversy and still chose not to, but maybe he wanted to created a talking point in what he recognised was a minor work 🙂

LikeLike

“Mocking Widow is OK but Crimson Blind… Brace yourself!”

Honestly, Behind the Crimson Blind is not as bad as some make it out to be. It’s bottom-of-the-barrel Carr, sure, but still an enjoyable read with H.M. being more out of his mind than usual. The Cavalier’s Cup was pretty decent for a late Carr. However, as someone once suggested, the story might have been actually good had H.M. been revealed as the culprit behind the ghostly activities in the locked room.

LikeLike

Is the opening fair? Boucher thought not.

Yours, though, is clever. Yep, it’s pretty much a dud – and some surprisingly racist passages for JDC. My solution, before I read the book, was that the victim was stabbed with a rubber knife, but hypnotised into believing it was real (operating on the latent deathwish). On that note, hocus pocus with amputated limbs can apparently affect their former possessor.

And speaking of possession:

“books, clearly bought by the yard and undead,”

Unread, surely? Although Carr would have told a good story about an undead book (a tome from the tomb).

LikeLike

Ha, thanks for catching that typo — I’m progressing from writing nonsense to writing words that spellcheckers don’t detect. I’ll have to hire proof-readers at this rate…

Is the opening fair? I dunno, possibly not, though I didn’t mind it — for the reader newish to Carr I guess not, but I’m used to his conditions on things and so read that particular line and tucked it away as something he’d more than likely come back to later. And, hey, it’s not as bad as the time (in another book) his detective, talking after the event of having solved the crime we’re about to read about, tells you early on that someone wasn’t the killer only for them to turn out to actually be the killer. That was just…weird.

LikeLike

I’ll never understand the controversy surrounding Seeing is Believing. Is the solution to the puzzle crap? Absolutely – possibly Carr’s worst. But does that one controversial element cross the threshold of fair play? Not at all. I think it’s a fun clever bit. If I’d never read another review of this book, I don’t think it would ever strike me that there would be any debate about that one key element.

LikeLike

I’m with you. Only upon reading other reviews did I see references to this supposed cheating, and it took me a few moments to figure out what it was referring to.

LikeLike

Only two things I remember from this one is H.M. dictating his memoirs and Carr cheating a little bit at the beginning, but everything else was pretty forgettable. As you said, it’s a bit shit, especially by Carr’s own standards.

“It occurs to me that this is probably the first dud in the Merrivale series…”

Oh, yeah, I forgot. You actually liked And So to Murder.

LikeLike

I will not play up to your And So to Murder baiting! It’s a much-maligned book with a very, very good central puzzle.

This one…slightly less so, we can agree. Doesn’t even have the interesting”glance behind the curtain” element of AStM. Who hasn’t seen people eating, or someone unexpectedly stabbed to death in their living room? *yawn* Come back when you’ve got something interesting, John.

LikeLike

Just skimmed this as I’ve not read the book yet myself. I have a reasonable enough copy (a Zebra reprint) so I had no idea it was considered a scarce one.

LikeLike

I couldn’t say for certain that it’s considered a rare one by anyone else, but this, Drop to His Death, and a handful of others are rare in my experience 😂

LikeLike

That’s another I got years ago- the Dover edition – but I agree copies of that seem a bit thin on the ground. I think I have all of Carr’s books now, apart from Devil Kinsmere, bar a few short story collections (Queer Complaints, Men who Explained Miracles) since I have all the stories in the Fell & Foul Play and Merrivale March & Murder and Door to Doom volumes.

LikeLike

Did F&FP, MM&M and TDtD contain no new material then? I know The Dead Sleep Lightly and 13 to the Gallows are previously uncollected radio scripts, but are those three collections simply the shuffling of some old pages to keep Carr in print? I’m not complaining in the least — keeping Carr in print is a wonderful thing — I suppose I was just always under the impression there was something new (previously unpublished/collected/rare) in them.

LikeLike

I think, although I’m not 100% sure and can’t check just now, that those three IPL collections have everything then extant as well as material that hadn’t been available elsewhere. Basically, if you’ve got those, then I think that adds up to all the short stories (and the long version of The Third Bullet), making it essentially unnecessary to own earlier collections.

I’d still pick up a copy of the Pan edition of DoQC just because it looks attractive and I’m a bit of a Pan junkie anyway – always too expensive for me though.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I can confirm this, Colin. If you have “The Door to Doom”, “Fell & Foul Play” and “Merrivale, March and Murder”, you have all short stories that had been collected previously, as well as a few that had not been collected before.

However, since their publication at least one other short story has been published: “Harem Scarem”, which I seem to recall was an early short story version of “It Walks by Night”. I don’t know if there are other short stories by Carr lying around – if so, perhaps Tony Medawar will unearth them for his “Bodies in the Library” series?

If you are also interested in Carr’s radio scripts (and admittedly, who wouldn’t be?), then you need to own “The Dead Sleep Lightly”, “13 to the Gallows” and “Speak of the Gallows”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Speak of the Gallows? I…had not heard of that one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It could be because it’s actually called “Speak of the Devil”. 🙂

LikeLike

That…that might explain it 😁

LikeLike

On the subject of uncollected Carr… There are some very early Carr short stories, not put in any book ever as far as I know, available on the Internet Archive. They were originally published in the Haverfordian (the literary magazine of the school Carr attended), volumes 46 through 48, and you can find them by going to the IA main page and entering “Haverfordian” in the search bar. “The Dark Banner” is a tale of old Heidelberg, “when faces were scarred and the sword blade was justice”. There’s also “The Inn of the Seven Swords”, swashbuckling in 1649 starring a character whose name will ring a bell with Carter Dickson’s readers, and “The Deficiency Expert,” about the newspaper business in small-town Pennsylvania. And there are the early Bencolin stories, collected in The Door to Doom, and Grand Guignol, the novella later expanded into It Walks by Night. Carr was young when he wrote all of these, but his style is very mature.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I believe that MM&M contains a short story two that hasn’t graced the pages of any other anthology. DTD contains some of Carr’s early Bencolin stories which hadn’t been republished since their original debut in the 1920’s. I don’t know about any other new material’s, but there probably is a story or two that I missed.

LikeLike

So these collections would account for all the previously-published collections, but not vice versa. Got it. Many thanks.

LikeLike

“I couldn’t say for certain that it’s considered a rare one by anyone else, but this, Drop to His Death, and a handful of others are rare in my experience ” Drop to His Death, certainly. A kind online friend back in 1980 photocopied his copy for me, as no others were to be had. I wonder if I could track those pages down now…..

LikeLike

Wow! That’s brilliant!

LikeLike

“A kind online friend back in 1980 photocopied his copy for me”

Is this what internet piracy looked like in the eighties? Internet users swapping cassette tapes and packets of copying paper through the mail.

LikeLike

I remember a friend of mine when we were much younger trying to copy a movie by watching it on VHS while also recording the screen with a crappy late-1980s video camera. His career in piracy was, suffice to say, short-lived.

LikeLike

The follow up to this – The Gilded Man – is on similar ground. It never reaches the heights of Seeing is Believing (I loved the set up), but it doesn’t feature the lows either. It’s sad to say that at this point, those brilliant Merrivales of the 30s are behind you.

LikeLike

…and that’s fine, everyone has a peak and so must decline afterwards, and once we’re into the late 1940s Carr is commonly accepted to dip anyway. This feels a little more stark because of all the brilliance around it, but maybe it’s good preparation for the sorts of books that were to come, so that the ones that shine brightly in, say, the 1950s aren’t still dazzled beyond recognition by the stuff he produced 15 years before.

I’m actually pretty shabby on Later Carr, as I only added a lot of that to my collection recently. Given how thoroughly enjoyable I’ve mostly found Later Christie, it’ll be interesting to see how Carr fares in the light of similar experience.

Plus, his interest in the Historicals would’ve revived him a bit, right? I mean, The Devil in Velvet ain’t a great book, be Carr’s clearly having a great time.

LikeLike

Speaking of The Devil in Velvet, I’m midway through it at the moment.

LikeLike

It’s Full Barmy Carr, just wild ‘n’ crazy swash ‘n’ buckle the whole way through. Deeply odd, but he’d probably not had that much fun for years. Will look forward to your thoughts on it.

LikeLike

I like Seeing is Believing, as it’s written superbly and it has a interesting impossible crime – but it feels almost hollow when compared to the past few works in the Merrrivale series. The solution is a cheat by almost any standard; but it’s a cheat that is very easy to see through and easy to predict. The impossible crime has a gimmicky resolution that doesn’t satisfy at all, and it feels very flimsy in retrospect.

I believe that this is the start of a new era for Carr. No more of the incredibly intricate puzzles and doom laden atmospheres of his earlier works; instead we get a more lighter and less complex fair from here, excluding a few works that manage to rise to the occasion.

Also, is this really that hard to find???? Whenever I go on Abebooks and look up Carter Dickson, this is one of those title’s that can be found in abundance. Of course, I’m an American, so maybe we just have a bit more luck in the used book department 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, you Americans roll out of bed each morning and trip over 47 books I’m trying to find. It’s an affront to my mild nature, to think of how many used books I’d be able to find on eBay US if I were “over there”. I even looked at jobs in the US for almost that exact reason, but, well, no.

The impossibility here is such a let down, especially as I was convinced the entire purpose of the book was to make some comment on the way people observe things as in Green Capsule. If I read that in a book today, I’d probably choke myself to death through all the scoffing I wouldn’t be able to help.

Still, the dual love stories do keep you guessing, and he has a good sense of place and atmosphere. The problem as phrased is wonderful, now we just need to come up with a better solution…

LikeLike

It could have been an interesting parallel to The Problem of the Green Capsule, but, well, Carr doesn’t exactly do anything with the similar concepts and instead allows almost no focus on the witnesses and potential psychology of the murder. The problem is wonderful, and it has so many possibilities, but they’re squandered in the end. A real shame …

If this story’s plot had been adapted by anyone in the modern day without Carr’s writing or skill – well, at least Angel Killer would then be considered a decent work 😉

LikeLike

Have you seen the four- and five-star reviews for Angel Killer? It is considered a decent work!!

LikeLike

How… horrific!

LikeLike

Life is full of wonders…

LikeLike

The puzzle really is wonderful though isn’t it? It’s a really shame that Carr wasn’t able to attach a satisfying solution to it. If he had, I think we’d regard Seeing is Believing amongst his top works.

LikeLike

Sure, but isn’t “If this was much better, it would be really good” something we can say about every poorly-realised book, film, TV show, etc? 😛

LikeLike

I’ve argued that Carr’s shift towards a new era began in 1938/39. To me, “The Crooked Hinge” and “The Judas Window” are his final twisty complex murder plots featuring lots of melodrama. The complexity stays for a while yet, but the melodrama is almost completely gone by the following novels. (“The Reader is Warned” might be the last one that relies on melodrama to some extent.)

And by 1940, Carr has become more of a “normal” fair play mystery writer. (I can’t comment on “The Man who Could Not Shudder” since I don’t have it fresh in my memory at the moment, so a caveat for that one.) He is still a terrifyingly good mystery writer for the first half of the 40s, but now he’s writing more based on experience than on enthusiasm.

And when enthusiasm falls away entirely (and age and health start to take a toll on him) the regular mysteries suffer, though I’d argue that it’s only by the early 50s that you have to be a true Carr fan to truly enjoy those works. Enthusiasm continues to carry the historical novels for yet a while thereafter.

LikeLike

There is arguably a lessening of his versatility around this time: he writes an increasing density of these household novels as I spoke about in the review: smallish cast, based mostly in a single house, where the setting is immaterial and the drama comes from more standard tropes of the genre as opposed to the wild invention of his earlier career where a variety of settings, people, and causes contributed (compare this with, say, the baroque majesty of The Bowstring Murders, or the house-bound but dazzlingly overcomplex Plague Court Murders).

“Experience rather than enthusiasm” might be my new euphemism for “well, it’s all a bit shit, isn’t it?” — outstandingly put.

LikeLike

I’ve argued that Carr’s shift towards a new era began in 1938/39. To me, “The Crooked Hinge” and “The Judas Window” are his final twisty complex murder plots featuring lots of melodrama.

Hmm, ok, you have me contemplating this a bit Christian. I think you’re mostly right, although I’d push the date out to 1941. The 1939 books (Wire Cage, Green Capsule, Reader is Warned) definitely fit the mold of the classic Carr era, and I feel like The Case of the Constant Suicides and Nine and Death Makes Ten do as well. If you were to tell me that Till Death Do Us Part, She Died a Lady (with the exception of the wheelchair scene), or He Who Whispers were written as part of that 1934-1938 pack, I’d believe it as well.

Seeing is Believing really is the book that straddles the eras for me. The set up of the book is pure classic Carter Dickson, fitting in amongst the likes of Plague Court, Red Widow, Ten Teacups, or any of the books listed above. Once we’re past that terrific setup though, the book slips more into the territory of mid-40s books like The Gilded Man, The Sleeping Sphinx, or My Late Wives. Fine books, to be sure, but a slightly different breed of mid-story focus.

And, of course, this is the book that started the whole “HM is involved in a zany past time” thing. It’s actually amusing in Seeing is Believing, and works fine in The Gilded Man, but it’s all down hill from there. Not to say the rest of the books are bad (although they are noticeably weaker than those that came before), but the comedy angle never really works.

LikeLike

I ordered The Peacock Feather Murders, but I notice your review is a spoiler, so I’ll have to finish the book before reading it.

LikeLike

There’s a discussion to be had about one of the more controversial aspects of that book, so I might pick your brains over it when you’re done…

LikeLike

I’ll skip any contribution to the annual (monthly?) in-depth analysis of JDC’s books, but I will chime in on proven facts.

A rare book? Really? Come on, it’s not even scarce. Maybe just “hard to find” in a brick & mortar used bookstore. But as soon as you do one single book search online this title shows up in abundance. I found 107 copies in both hardcover and paperback offered for sale. And I have no idea what Steven is talking about way up in the first comment. This book was reprinted six times in the US alone: G&D (hardcover), Tower Books (hardcover), Pocket Books – twice, Berkley, and Zebra.

LikeLike

Ha. Well, it has been reasonably well-established that I am terrible at secondhand book scouting — and, yeah, I try to do as much as possible in real shops rather than online. Possibly you’re at an advantage being in the US as was suggested above, do you think? Or perhaps you’re just much better at this than I am, John 🙂

Might have to hit you up for some links, since I’d dearly love to complete my Carr my Crofts collections, and the possibility of affordable copies gets ever-less likely the longer I leave it…

LikeLike

I think I can empathize with the rarity a bit. You have to take into account both availability and price. I’m hard pressed to spend more than $12 on a vintage book, and even in that case it has to be a really nice edition. The last book I bought for $12 was Clayton Rawson’s The Footprints on the Ceiling, and that was only because it was a Dell map back (immaculate condition as well). I think the most I’ve ever paid was in the neighborhood of $16 for The Hungry Goblin. Most of my books are in the $3-8 range.

So, yes, there are plenty of copies of Seeing is Believing to be had, but how many in the range that you would pay for? I can’t say, as I picked mine up fairly early on as part of a bulk purchase of 1968 Berkley Medallion edition Carrs.

I did have a frustrating experience with The Sleeping Sphinx though. Similar to JJ, I was at a point in collecting Carr where I only had 3 or 4 books left to go. When you have your eye on specific titles, they become impossible to find (at a good price at least). After months of searching, I finally snagged my copy. Of course, books are only hard to find when you don’t have them. Two weeks later I ended up getting a second copy of The Sleeping Sphinx as part of a four book pack – the purchase of which was targeting another book entirely (Patrick Butler for the Defense).

Oddly, one of the hardest books for me to track down was Carr’s most popular title – The Hollow Man. Copies were either super expensive or some dreadful 90s/00s edition with generic covers. I wasn’t going to settle for that for this specific book. I think it took me about six months to finally snag an IPL edition for a reasonable price.

LikeLike

It took me a very long time — and some very considerate friends — to track down a bunch of Carr’s post-1950 work, and with most of the now in my possession I’ve hit a complete blank on the remaining ones, and it’s only thanks to Puzzle Doctor that I’ve read this and Drop to His Death. Someone was giving away a bunch of Carrs on the GAD Facebook group, but the ones I don’t ave went in the very first request someone made…so who knows how long it will be before I get another chance? I’m sure it’ll come, but now it’s a waiting game.

Like you, I don’t have infinite funds to pay the increasing prices of these older titles in the sort of condition I prefer (and, hey, I’m very realistic about that). I lucked out with a stack of the House of Stratus Crofts titles last year, and now only need three of his, too, as I think I mentioned elsewhere, but those books are rocking-horse-shit rare and go for the sorts of prices I just cannot allow myself to spend (it’s a slippery slope…!).

The Hollow Man was an odd one for me: the first I read, but I didn’t find any other decent editions for years (it’s been in print in the UK for ages, so the modern editions tend to predominate). The, I found three editions in a the same week. Equally, The Nine Wrong Answers — I gave up on that a number of times, and then found three editions in the same month.

Now, sure, these are the most hilariously First World Problems going, so let’s not get the impression my life is unable to progress until I find these books, but I think it’s interesting — like Ben addresses above — how “rarity” is a very relative term. Five years from now I may have seven copies of Drop to His Death…or none still. That’s part of the fun of trying to collect these OOP authors.

LikeLike

I feel like I’m in potential spoiler territory here. So I will come back after I’ve read it (probably in about two years), and the thirty of us can pick up the conversation where we left off.

LikeLike

Nah, you’re safe from spoilers, but I can understand your desire to read as little as possible in advance. See you in 2023 for your thoughts and my poorly-phrased evasions trying to hide my lack of recall.

LikeLike

Thanks for the review, JJ. I recall enjoying this title moderately – I liked it, but not more than the average mystery novel, and kept mixing it up with “Sleeping Spinx” as both titles were not Carr’s strongest efforts. I definitely thought the opening chapter of “Seeing is Believing” fell short of fair-play – and it didn’t need to have.

I did a preliminary search, and I think you can find a second-hand copy for a US bookdealer for under £10 (including shipping costs). The condition is stated to be “good”. I was about to put in the link – but feared that my post my end up in spam. 😅 I’ll email it to you?

LikeLike

Thanks for the offer, but I’m happy to hold out a while to see if I can find this in a shop — I’ve just read it, after all, so there’s no rush 🙂

I do love how debated the nature of fair play still is, it’s a source of fascination to me how the interpretation we put on something is as important as simply being told something is true. At times like this my tendency is to lean into the belief that Carr and his ilk were simply toying with the notion of disclosure, but then I remember the couple of times when he outright lies for no good reason and that sort of destroys my argument…

LikeLike

A few scattered thoughts:

Carr really doesn’t put a lot of effort into setting up the Phil-Ann romance. He takes one look at her, BAM, he’s in love, and she seems to fall for him with equal ease.

I agree with Suddenly At His Residence that this is definitely not one of Carr’s better impossibilities – the mechanics of the switch verge on parody. And I agree with everyone who says Carr does not play fair in that early piece of misdirection.

This was one of those Carrs where the puzzle and solution are less interesting than the things we find out about the murderer and that character’s actual relationships with some of the other characters. Not one of the strongest as a mystery, but one of the books I went back and reread after finishing it so I could view things in their true light.

LikeLike

Carr pulls the last-minute romance out of the bag a few times — Nine–And Death Makes Ten being an example that sticks in my head for someone on the last page going “Well, you’re the man in the story and you’re the woman in the story and so you should fall in love” and them looking at each other and going, “Sure, why not?”. Slightly troubling…

Calling this “not one of Carr’s best impossibilities” is, perhaps, the most flagrant understatement of the last decade. It’s terrible, and so far beneath the standards Carr was setting at this time (c.f. The Reader is Warned, Constant Suicides, etc) that it can only possibly appear passable on account of how diluted we’re used to the impossible crime having become in most modern swings at it. I don’t even hold that arguable misdirection against him. It’s just bad, and laughably ridiculous the more I think about it.

The household is well-handled, and he gets a good accidental alibi out of someone, but it feels very much like autopilot for the majority of this. Without a great surprise as the payoff — like all those people who didn’t see through The Emperor’s Snuff-Box felt at the end of The Emperor’s Snuff-Box — it occupies a weird shrug-worthy notoriety in my mind. I wouldn’t actively dissuade anyone from reading this one, but I’d give them solidly 50 or 60 other Carr books first.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you want an example of a ridiculous last minute romance, look no further than Patrick Butler for the Defense. I can’t think of a better example of “we’ve known each other for six hours, let’s get married.”

LikeLike

So the Central Man and the Central Woman get it together at the end? Spoilers. Ben, spoilers!

LikeLike

Well you drew my attention to a JDC book I seemed never to have heard of, and then explained why more or less, and so now I will have to try to read it… even if not his best.

LikeLike

I love how the response most people seem to have to an indifferent review of mine is “Oh, man, I have to read this book!”. Do I have that much of a reputation for being…in fact, what even sort of a reputation is that? 😛

LikeLike

Simple. Enthusiasm breeds suspicion, dismissal breeds despair, but indifference breeds intrigue.

LikeLike

…and intrigue leads to the Dark Side…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you still not have a copy JJ? Are you fussy about condition etc? If not – I have a copy I can either post to you or bring to Bodies in June. Am posting on the book today, and will explain why I have a spare… (entirely your fault, is generous of me to offer it).

LikeLike

I’m a tiny bit fussy about condition, but I won’t turn it down — many thanks!

LikeLike

It was Rich at Complete Disregard for Spoilers who commented that the “cheat” is unfair because it’s John Dickson Carr who wrote it. An interesting post, I think.

I should read this sometime, although I’ve been spoiled pretty badly on it. This is probably the most creative use of hypnosis I’ve seen in a mystery, so even if the solution is a disappointment I’ll probably have to read it based on that alone.

LikeLike

Undoubtedly this is one of the few times hypnosis is used without feeling forced or unlikely to allow a machinations of the plot (cf D**t* *r** a **p *a*). Would love to read something else that used it as well, you make a great point.

LikeLike

I seem to be the only one who likes the mechanics of the solution. Risky, for sure, but worth the risk maybe.

LikeLike

I suppose it’s not so much the element of risk that I object to as the sheer lack of ingenuity. This is Carr, and he gives you a solution that literally anyone — any part-timer, any clueless newbie, any jaded and resigned veteran — could have written, lacking any genius insight or misdirection or…anything notable, clever, interesting, even half curious. The setup is pure Carr, full of potential, and the payoff does not even slightly live up to it.

LikeLike