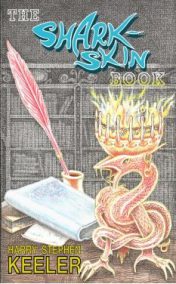

This week, for my actual final post for the Tuesday Night Bloggers on the subject of travel (I was, er, premature in predicting the number of days in May last week…), I was going to look at another book entirely. But in reading The Sharkskin Book by Harry Stephen Keeler – chief loon of the sanatorium that is Ramble House – I was struck by something rather more nebulous that I’m going to try to explore here: the sense of dislocation one can experience when separated from familiar trappings.

The Sharkskin Book is composed of three separate stories, and it’s the first two I want to look at – the first starts with Ogden Farlow under arrest for murder and being subjected to a ‘third degree’ interrogation by three police officers: one American, one Italian and one German. It’s possible I missed the reason for this smorgasbord of nationalities, but it’s the use of phonetic speech across these accents that got me thinking along the lines I’m hoping to explore. Like Jim Thompson, Keeler uses speech above action as an insight into character:

“[H]e asked him who you both were. But particularly – the dame. And van Dervepen was just drunk enough to tell him that you were some guy he lived with, and the dame was a burlycue or some goddamn kind of a teaser dancer…”

It’s true that our Italian and German friends aren’t portrayed quite so…carefully, but the bewilderment felt by Farlow is exploited perfectly by the phonetic nature of their speech:

“An’ eef eez not the case – an’ we ‘ave to fin’ Joe Long – and heez som’ dam’ smart creem’nal lawyer, then we ‘ave fin’ theez man some mout’piece dat way!”

What this leads on to is the second story thread concerning Joe Long-Buffalo who (and this is early enough not to count as a spoiler) far from being a dam’ smart creem’nal lawyer is in fact a Native American who comes to Chicago for reasons of his own. And this is where the notion of travel kicks in – Keeler has prepared you for the sense of the given protagonist feeling separated from his surroundings with Farlow and his police escort, but now Joe is a man outside of what he knows from his first appearance of getting off a train surrounded by other travellers:

Occasionally one, looking back, held his gaze uncommonly long on Joe Long-Buffalo, and Joe wondered whether it was because he was an Indian, with high cheekbones and copper-colored skin, or whether it was because of that confounded green-striped mail-order suit which fit him far too tightly, his too-loud checkered hickory shirt, and his wide-brimmed – and entirely out of season – straw hat which, he knew now, with his too long black hair, branded him as a hick from the country – a thing which, in sooth, he admitted himself to be!

What we get through Joe is a view of Chicago where he is the reader’s avatar and everybody else is foreign. Joe’s speech is written in the same standard English as I am writing this sentence, and it’s the people he encounters – those on home turf, so to speak – who are presented through idiomiatic speech, literal lingual representation, and, tellingly, a fascination with Joe as the foreign element. Not for Keeler the hick being overwhelmed by the Big City and its Ways, but equally he doesn’t simply flip the expected dynamic on its head by having Joe be the civil one and everyone else the Big City Hick:

The old man’s face brightened up. “‘Scuze me sir, for takin’ ye to be some Injun off’n the rese’vation. I see yer even a-a-a collidge Injun, mebbe? Wa-all – so ye wuz advised to ask me so’thin’, eh? Wall, ef I kin he’p you any, I’m on’y too glad to do so. I b’en in this hyar city fur 15 long y’ars – so they hain’t much, I reckon, I cain’t talk a’bout.”

“I would judge,” said Joe politely, “from your – er speech – that you were a newcomer like myself?”

“Oh, that’s on’y caze I talk that thar Big River dialec’, boy. I come hyar f’m mebbe hund’ed miles west o’ Big River – not so durned fur from Memphis, in fac’ – but we’uns of Big River never lose out speechin’s – and they ain’t never nobody ever could put our speechin’s in a book or imytate us.”

It’s a truth long-established that Western society as a whole was slow to react to the differentness of other cultures and, particularly in print, this has led to the portrayal of people and attitudes that are somewhat regrettable –

It’s a truth long-established that Western society as a whole was slow to react to the differentness of other cultures and, particularly in print, this has led to the portrayal of people and attitudes that are somewhat regrettable –

Interesting and intelligent post. I’m glad you survived your Keeler experience. Books which treat the West as “other” are always interesting to read, though for GAD fiction it is usually not done so extensively and overtly than it seems to have been here.

LikeLike

An interesting and intelligent post indeed! What occurred to me is that we, as 2016 readers of books written in, say, 1925, often have that dislocative sense of familiarity/unfamiliarity “in the presentation of one person’s everyday as foreign and just out of reach in terms of comprehension to someone else.” The people in Golden Age mysteries are people, and on some level we understand them, but then they start talking about the servant problem, or the impossibility of divorce, or who walks in before whom as everyone goes in to dinner, and the comprehension becomes foreign and elusive. The “distant lands” become more odd because in many ways they are the same as our own lands.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a nice analogy, actually – it’s interesting just how much I think I understand about the era these books were written purely from repeated references to certain aspects of life (taxation during the war being a key one!). I’m probably miles off – images of the Past-O-Rama theme park from Futurama spring to mind – but that separation is definitely heightened but the odd sense of familiarity undercutting everything.

The interesting thing is when anachronisms we’ve lost touch with become key aspects of the plot or the workings of the deception – I’ve already mentioned before the passports in Murder on the Orient Express, but there’s equally a leap made there due to a brand of (I think) baby food that’s now defunct – and it’s telling then just how isolating the references become.

LikeLike

I think there’s a whole monograph to be written about the idea of how telephones work in Golden Age mysteries. “Hello, Central — can you trace that call?” Today’s iPhone-using millennials will need a guide to explain the party line, trunk calls, and how Miss Marple’s phone number could be something like “St. Mary Mead 3”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember the very first time I read a book which relied on the existence (or possibly otherwise…) of a party line – it was something I’d had no idea existed, and took a bit of figruing out from what was written (at a time, of course, when it would require no more explanation than downloading an app would now). A fair few alibis have rested on operators connecting calls, too, now that I think about it…it’s weird how normal that kind of thing seems to me even though I neve lived to see it myself. “People say that life is the thing…” and all that!

I do love the fact that little things like that, while lost from daily experience, are never truly lost while it’s possible to revisit that sort of unfamiliarity in these books. It’s something which needs preserving, I feel, though my precise justification for this is currently a little unformed…!

LikeLike

You’re being damn deep, if you ask me! And it is absolutely deee-lightful to see Noah Stewart here! Hope you’re well, Noah!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remain utterly fascinated by Keeler’s bizarro reputation but remain hesitant to take the leap … but this sounds very intriguing none the less. Thanks.

LikeLike

Am I right in my surmise that you’ll be at Bodies from the Library this year, Sergio? Because, if so, you’re very welcome to my copy of this; I’m unlikely to re-read it – I prefer Thompson’s approach to the pulps – and I’d like to think of it going to a good home…

LikeLike

Well, that is a very kind offer – I do hope to be there but have not got a ticket yet – promise to confirm!

LikeLike

Would you recommend any of the Harry Stephen Keeler titles in particular? For some reason the only Random House books that my local Amazon Kindle shop offers are those by Keeler… As well as one or two obscure titles by Max Afford.

LikeLike

I’m sorry to say that this is the only Keeler I’ve read. As to whether it’s the best place to sart…well, I didn’t love it, but then it reminded me a lot fo Jim Thompson and – frankly – anyone who inspires a Jim Thompson comparison in my head is probably going to lose out from that point on!

I’ll come back to Keeler, but as to where, that’d pretty much be a guess. Fender Tucker, he of Ramble House, has put together this handy guide of where to start with Keeler, though, if you’re looking for inspiration from someone who knows him well…hope it gives you something to work with!

LikeLike

Pingback: #107: Vintage Cover Scavenger Hunt Update | The Invisible Event